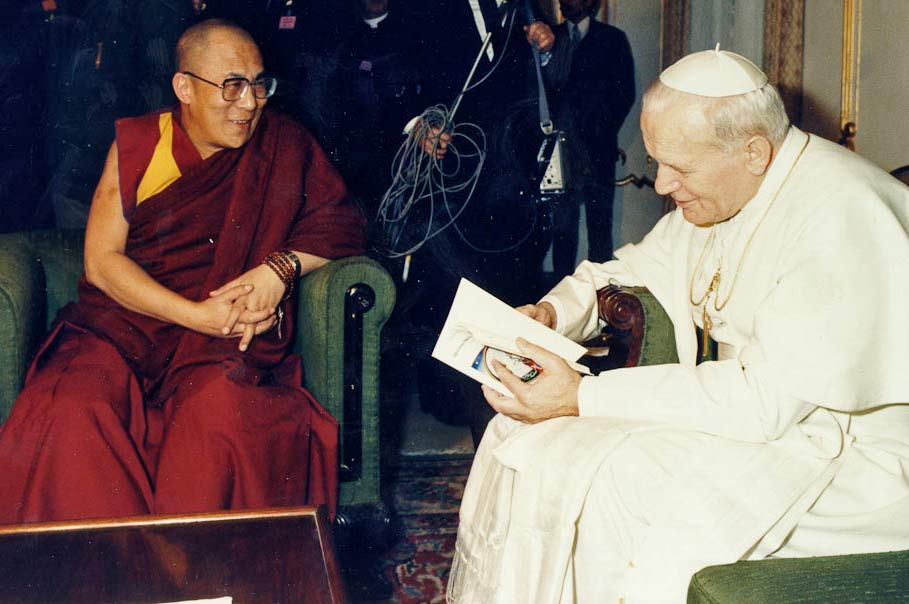

The Dalai Lama with Pope John Paul II, Vatican City, June 14, 1988. (Photo: www.dalailama.com)

His Holiness was very much welcomed in Rome where the audience gave him a standing ovation at the venue of the Summit.

At the same time, in what was the biggest public relations failure by Papa Bergoglio since he ascended to the seat of San Pietro in Rome in 2013, the Vatican did not grant to His Holiness a meeting. Instead he issued a public statement saying that the Pope holds the Dalai Lama “in very high regard”, in a recognition of the high opinion that hundreds of millions of Catholics all over the world have for the Tibetan spiritual leader.

So why not meet him? The answer is simple. The Chinese Government uses the “Dalai Lama card” to put pressure on all its international partners, both to put them on the defensive (typical behavior of aggressive negotiators) and most importantly because it fears that the moral authority and legitimacy that His Holiness has gained worldwide might be transformed in pressure to implement much-needed political reforms in China and Tibet.

Contrary to China’s calculations – betting that isolating him politically will resolve the Tibetan question – the Dalai Lama anticipated China’s aggressive campaign by voluntarily and willingly choosing to abdicate his political authority in 2011. This, among other long-term factors, including China’s bullying, has not undermined, but rather increased the popularity in the west of the 14th Dalai Lama.

With this decision and a step forward to dedicate himself to promote peace and interreligious dialogue, the Dalai Lama had hoped to facilitate a meaningful political dialogue between the Tibetan and the Chinese sides. Unfortunately, China continues to act aggressively, hoping that the problems in Tibet will be solved through their current policies.

Certainly, as a Tibetan, the Dalai Lama remains concerned with the deterioration of human rights and individual freedoms in Tibet, but it must also be noted that the he tries all the time to highlight potential positive developments that are taking place in China. Furthermore, in regards to the foreign leaders who have stopped meeting him in Europe, he continues to repeat that he does not want to create any inconvenience to the countries that are eager to make business or have good relations with China. The problem is, clearly, what kind of long-term relations can be established with an authoritarian country that does not apply the rule of law and whose judicial system is highly corrupt?

With this in mind, the way China continues to pressure everybody in the world not to meet His Holiness tells us a lot on how insecure Beijing is about its policies in Tibet, and shows its failure to grow as a responsible partner for democratic governments on the world scene. Getting away with bullying the Tibetans is only going to encourage the hardliners in Beijing to do this on other issues and to other peoples and countries.

For Pope Francis, who has courageously challenged the Vatican bureaucracy on many fronts (from its shadowy finances to the cover up of sexual abuses within the Church, from a renewed dialogue with Muslims and the Russian Orthodox to recommit the Church to help the poor and shelve luxury living styles), to give up on the promotion of interreligious dialogue with the Dalai Lama is a striking contradiction with what he has been preaching from the pulpit.

While tactically this move might bring some benefits to the Vatican in its dealing with China – the Vatican has been trying hard for decades to establish diplomatic relations with Beijing and the Chinese Foreign Ministry had a positive comment in response to the – this choice makes clear that the promotion of religious freedom for all in China is not a priority for this papacy. This is a stain that will not fade until urgent remedial measures are taken.

Matteo