Protests at Parliament square.

he day before UK PM Cameron entertained Xi Jinping for a pint in his local pub last week, a Chinese Tiananmen survivor and two young Tibetan women were locked up overnight by police in London and informed they were not allowed to be ‘within 100 metres’ of the ‘victim’ of their ‘harassment’, Chinese Communist Party boss Xi.

It was a troubling conclusion to a week in which the UK government faced an angry public backlash to ‘the great British kowtow’, in which the authoritarian leader of the Chinese Communist Party, currently presiding over the most serious crackdown in the PRC in a generation, was accorded a glittering surfeit of Royal pomp and obsequiousness in line with Chancellor Osborne’s new China policy of doing whatever the Beijing leadership wants.

As the golden carriage bearing Xi Jinping and the Queen progressed down a Mall lined with cheering Chinese students with immense red flags, uniform tee-shirts, drummers and dragons, dissident writer Ma Jian had tears in his eyes. “The message from the Chinese tyrants to their subjects is clear: if the queen of the UK, the oldest democracy in the world, lavishes your president with such respect and approbation, then what right have you to criticise him?” Ma Jian wrote.

Sonam and Jamphel, the two Tibetan protesters arrested during Xi Jinping’s London visit, welcomed by members of the Tibetan community in London on their release.

There were numerous attempts by the Chinese students and security personnel to obscure or intimidate the small number of Tibetans, Chinese (Falun Gong and others), Uyghur and other protesters on the Mall.

Carole Beavis wrote that she was “singled out by three official looking Chinese men, who effectively herded me away from the event, lowered my arm holding the camera.”

Xi Jinping’s visit to the UK coincides with a terrifying crackdown on civil society in China in which lawyers and human rights defenders have been targeted, with many enduring horrific torture. More than 140 Tibetans have set themselves on fire, an act emerging from anguish at unbearable oppression, while moderate Uyghur academic Ilham Tohti is serving life in prison for peacefully advocating dialogue.

But it is not only within the PRC. Xi and the top Party leadership are aggressively seeking to export their assault on civil society and to roll back freedom and democracy in other parts of the world.

The three arrests in London last Wednesday are in the context of police being pressed elsewhere in Europe to take stronger measures against peaceful demonstrations (for example in Denmark and Belgium.

Shao Jiang’s protest took place as Xi Jinping arrived in the all important ‘square mile’, the financial centre of London (Chancellor Osborne wants London to be the worldwide center for renminbi trading).

TV footage shows Shao Jiang, a British citizen who was imprisoned for 18 months after involvement with the Tiananmen Square protests, stepping into the road with two small white placards bearing the statements ‘end autocracy’ and ‘democracy now’. Several police officers charge towards him, knocking him off his feet, helmets flying, and take him into custody.

Soon afterwards, two Tibetan women who had been displaying Tibetan flags nearby were led away by police and all three held overnight in the cells.

At the police station that night, the duty officer told me that they were accused of ‘conspiracy’ ‘to commit threatening behaviour’. But Shao Jiang had been on his own – could they mean that perhaps he had been thinking of standing in another part of the public highway with his two placards? Perhaps the two young women, Sonam and Jamphel, were conspiring to go and grab a cup of tea afterwards, as it was a grey and rainy day?

As they were being held in custody, police went to each of their homes and seized laptops, phones, and USB sticks. All three depend on their laptops for work; the computer of Johanna Zhang, Shao Jiang’s wife, who works as an artist and translator, was even taken. This was a chilling step, particularly given the obvious resonances; in Tibet and China, people understand the visceral fear associated with a knock on the door in the middle of the night.

Chinese Tiananmen survivor Shao Jiang is released on bail at Bishopsgate police station (charges are now dropped) by Tsering Passang, head of the Tibetan Community in Britain, and Kate Saunders.

In a debate in Parliament on Monday (October 26), Shao Jiang’s MP, Emily Thornberry, asked for the Home Office Minister to advise her “how I can hold to account those who made the disgraceful decisions to arrest someone who was, on the face of it, behaving in a way that was entirely peaceful, who should not have been arrested and whose house should not have been searched?” MP David Winnick, referred to “British police action with Chinese characteristics”. (

Video available here.)

The arrests made front page news in the UK, in the context of an overwhelming public backlash against the UK government’s ‘epic kowtow’ to Communist Party boss Xi. Business leader and expert on China James McGregor, chairman of consultancy APCO Worldwide, told the BBC’s influential Today programme: “If you act like panting puppy the object of your attention is going to think they’ve got you on a leash. China does not respect people who suck up to them.” Mark Steel mused in The Independent: “If trade helps improve human rights, it’s about time we let North Korea and Isis run some of our industries.”

Steve Hilton, the UK PM’s former strategy advisor, tore into his friend Chancellor Osborne, arguing that kowtowing to China does nothing for Britain’s economic health: “Of course the Beijing oppressors would prefer not to be lectured in public on human rights. But if a convicted murderer said he’d prefer not to be lectured in public on the morality of killing people, would we say: ‘OK, we’ll keep your verdict secret’? […]

China is a superpower, aggressively spreading its influence. Our security and economic opportunity depend on an orderly world, underpinned by the values of openness. We need to stand up, strongly, for openness. If the world slides towards the opposite values, those of the Beijing dictators, we should be very nervous.”

In the meantime, The Times reported that senior military and intelligence figures have warned ministers that plans to give China a big stake in Britain’s nuclear power industry pose a threat to national security (see this great video).

In a bizarre media postscript to the visit, I was invited to join a Sunday morning TV show on which Ken Livingstone bucked the trend with the bizarre claim that the Dalai Lama had no credibility because he was a CIA stooge, while TV presenter Tricia Goddard did agree that the Duchess of Cambridge’s dress at the state banquet was a step too far.

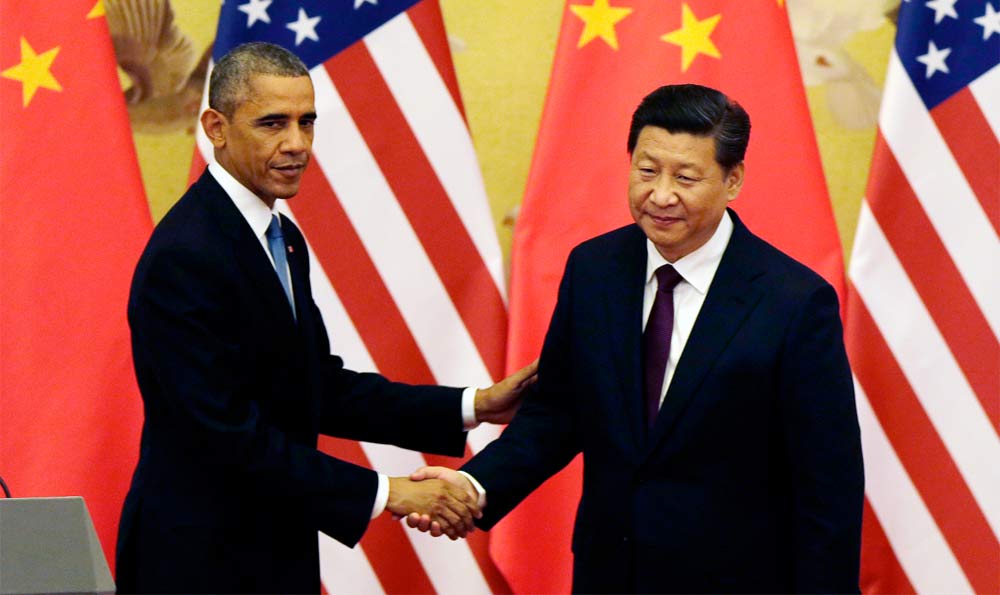

Kate looked stunning as she clinked glasses with President Xi, but did she need to wear red, in homage to a man who is China’s most authoritarian and paranoid leader since Mao? A man who is so controlling that he even banned cartoons of Pooh Bear, after Chinese micro-bloggers picked up on an uncanny resemblance between a photograph of Xi and President Obama and a cartoon image of A. A. Milne’s cartoon creations.

As if to prove that another approach is possible, this week Dutch King Willem-Alexander made a strong public statement by raising human rights at a state banquet in the Great Hall of the People in Beijing.

On Wednesday night, two days after questions were raised in Parliament about their arrests, Scotland Yard said that the three protesters had been “released from their bail with no further action”. Their laptops and phones were returned today.