The 49th day after death is an important landmark in Buddhism. In the broader context of the theory of the transmigration of consciousness, it takes at least 49 days after death for the consciousness to proceed on the path of rebirth. It is believed that rites conducted during this period – known as Bardo (intermediate stage)—can help to guide the consciousness toward a good rebirth. But a Rinpoche is also believed to have the ability to determine the nature of his rebirth.

Nevertheless, the timing provides one with the opportunity to look back at Rinpoche’s life in a less emotional way than was possible in the immediate days following his passing on October 29, 2018 in San Francisco. The coverage in the international press about Rinpoche outlined in detail his contributions and is a testimony to what he meant to the community interested in Tibet and beyond. The International Campaign for Tibet, which was the base of Rinpoche’s work from 1991 until his retirement, has encapsulated his lifetime of service in its report.

I was fortunate to have worked with Rinpoche, in one way or another, from 1984 until his retirement in 2014. While he was my boss for around 30 years, he was also my mentor and guide.

What have I learnt from and about Gyari Rinpoche? Here is a partial list.

Rinpoche was a strategist. He was someone who did not wait for opportunities, but ventured forth to create them. Whether in Dharamsala or subsequently in Washington, D.C. he did not look at the issue that he was dealing with in isolation, but tried to put that into context. He did this to get the best outcome rather than merely doing a checklist. One clear example is about visits by His Holiness the Dalai Lama to the United States and specifically to Washington, D.C. (of which he was directly in charge as the Special Envoy). In organizing such visits, Rinpoche was strategic even before proposing a visit or acceptance of an invitation so that the visit had a well laid out objective beyond the immediate programs. He consulted the leadership in Dharamsala, strategized with officials of the host government, and worked on creating a proper environment with concerned offices even before the visit. This included identifying concrete programmatic and policy outcomes. After the visit, he would follow up for their implementation. That is how many of the initiatives on Tibet, including the Tibetan Policy Act of 2002, came about in the United States.

I can recall a few major initiatives where I saw him implement this sort of strategic vision. In 1990, Rinpoche coordinated the first-ever International Conference of Tibet Support Groups in Dharamsala and those who were present then can testify how the conference energized Tibetans and Tibet supporters alike. At the conference a “long and ambitious list of new global strategies and initiatives was drawn up” which is a benchmark against which today’s Tibet movement can be measured, nearly 30 years later. Among specific suggestions from that conference were “to initiate international Tibetan Flag Days, to set up a computer information network (TibetNet), to internationally publish the destruction of Tibet’s environment, to campaign more effectively with dissident Chinese students abroad, and finally: to intensify lobbying at the UN or through other governments and non-government bodies.” EcoTibet (no longer active) was in fact founded thereafter for Tibet groups to take up the Tibetan environmental issue. Also discussed then was the establishment of an inter-parliamentary network of parliamentarians who are active in raising questions on Tibet.

Similarly, he outlined the strategy that eventually resulted in the United States Congress bestowing His Holiness the Dalai Lama with the Congressional Gold Medal in 2007. When the historic event finally took place on October 17, 2007, everyone, including Administration officials, members of Congress, Tibetans and their supporters, returned home feeling ownership and having a stake in it. This also reminds me of how Rinpoche coordinated an international strategy in the wake of the Nobel Peace Prize to His Holiness the Dalai Lama in 1989. I was then a junior official but felt empowered when I was part of that strategy tasked with producing the commemorative medallion.

Rinpoche worked at many levels. In the mid-1980s, at one level, he oversaw the development of a new Tibetan font for letterpress printing that was used by the Narthang Press in Dharamsala, until the onset of the digital typesetting. At another level, he was leading an international coalition of groups representing communities under Chinese Communist Government oppression. If you happen to come across old issues of a journal, Common Voice, that is one of his ideas.

In one sense, Rinpoche was a maverick. He always tended to look at issues beyond the confines of Gangchen Kyishong (as the seat of the Tibetan Administration is known), searching for new ways to take the Tibetan issue to the next level. In the process, he was all for taking advantage of the resources, including human and material, in order to reach this goal. He would enable those working under him to think outside the box, and provide resources accordingly. Those of us who have worked closely with him have heard him say in an understated manner that he only had one quality: he got the best possible people to work for him and let them do their job. However, the truth is that he had a well-planned strategy and got the staff to implement that.

Although, he personally did not take up technological gadgets like a computer (iPad became a companion in later years), he went all out to provide such facilities to the office he was connected with or to make the best use of them. In my early years in Dharamsala, when not just the Central Tibetan Administration, but Himachal Pradesh state as a whole, was only beginning to hear of something called a fax machine, he was able to get one for the Department of Information & International Relations. Similarly, his mobile phone was indeed his mobile office and if one has to think of a caricature of him, it might be him with his phone. In addition, if I recall correctly, he was the first Tibetan official to have a telephone connection at his residence in the early days in Dharamsala, and put it to good use.

He looked at the dialogue process with the Chinese Government — the main task assigned to him by His Holiness the Dalai Lama from 1997 – in a strategic way. As he would tell concerned Tibetan officials, dialogue did not merely mean the few days of actual talks that might take place with Chinese officials. Rather, it involved building the necessary support base among governments and in the international community so that the few days of talks can have the needed outcome. He implemented that by building a coalition of governments whose representatives met regularly to strategize with him, in Washington, D.C., and elsewhere. Through such interaction, Rinpoche was able to convey the vision of His Holiness the Dalai Lama and plan forward movement.

Some people have different views on the outcome of the 2002-2010 dialogue process that he led without considering the actual achievement. On September 28, 2002, after the first round of the talks with the Chinese officials, Rinpoche issued a statement in which he said, “The task that my colleague Envoy Kelsang Gyaltsen and I had on this trip was two fold. First, to re-establish direct contact with the leadership in Beijing and to create a conducive atmosphere enabling direct face-to-face meetings on a regular basis in future. Secondly, to explain His Holiness the Dalai Lama’s Middle Way Approach towards resolving the issue of Tibet. Throughout the trip, we were guided by this objective.” Therefore, if you look at the marching orders that the envoys were given no one can deny that these two objectives were fulfilled even though talks stalled in 2010.

Rinpoche’s work style was such that he made everyone involved in his project feel as a stakeholder. This was apparent whether he was dealing with different Tibetan organizations or with governments whose help he sought to help with the dialogue process. This even resulted in many of the officials and other individuals taking the lead in proposing strategy or plans as if the issue was more for their interest. It was also true for the Board members of the International Campaign for Tibet. They would listen to his passionate explanations — whether about His Holiness the Dalai Lama’s plans or his own ideas – as well as how ICT could contribute towards fulfilling them. This eventually made the board members into partners in the endeavor.

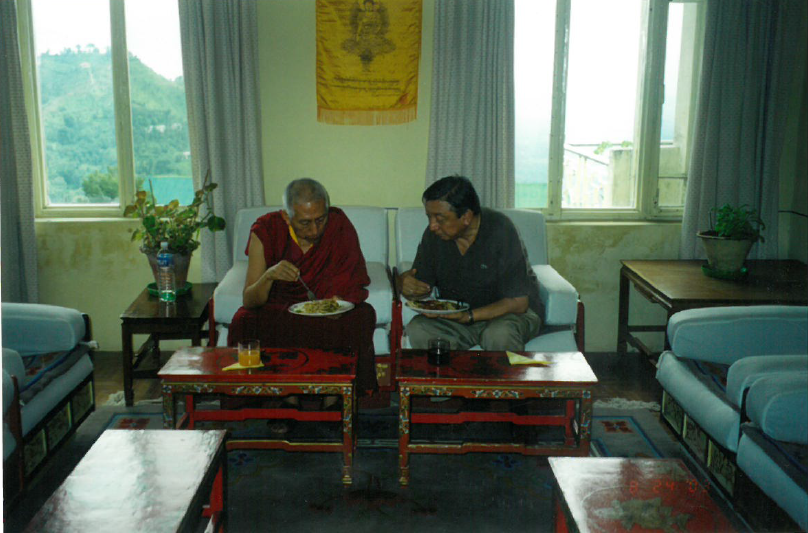

He would move beyond professional relationship and personally symbolized the nature of the people and the culture that he was asking them to help. I vividly recall many instances when senior Administration officials would literally sit alongside Rinpoche and chart out a plan, which they themselves ended up implementing. He was on a first-name basis, if that is the standard, with many influential individuals. On a lighter note, this even resulted in the well-known Congressman, Charlie Rose, establishing a tradition of sending Rinpoche’s family a turkey around every Thanksgiving. Similarly, he involved his whole family in this endeavor of cultivating friends, with his wife, Dawa Chokyi la, and his home serving as hosts for countless meals and meetings.

As for Tibetan officials, those who worked under him would testify to the fact that he literally and figuratively treated all of us as colleagues. Even while respecting the fundamentals of bureaucratic protocol, he went out of his way to establish a personal relationship, in addition to a professional one, with his staff. When he saw a potential in an individual, he would do everything possible to encourage his or her advancement, which he would say would eventually be for the greater good.

Rinpoche was someone who cared both about the substance as well as about the symbol. Those who can recall events such as those surrounding the Nobel Peace Prize celebrations in 1989, the conference in 1990, and the Congressional Gold Medal event in 2007 will know that when there was substance Rinpoche went all out to make the best public presentation, too. He would often tell us that even though Tibetans are living not in an ideal situation, we should always act in ways that can bring us respect and credibility. He would quote a saying in Tibetan that can be roughly translated as, “Even if we can’t be extravagant, don’t present an impoverished image”.

Rinpoche was always for Tibetans taking the lead in the Tibetan issue. He would poke fun at himself by telling our non-Tibetan colleagues that he knows they sometimes see him as a “control freak”, but that he believes that as a Tibetan and the Special Envoy of His Holiness, he needed to assert himself. Similarly, he would tell Tibet supporters that since they are there to support the Tibetans, they should leave decision-making authority to the Tibetans.

Above all, Rinpoche understood the privilege he had in serving His Holiness the Dalai Lama. His approach towards fulfilling His Holiness’ vision was a holistic one, going beyond the superficial level. While because of his spiritual devotion and political respect it was natural that he would honor His Holiness’ wishes, yet he did not rely merely on that authority while implementing them. Rather, he took time to study them and to provide a rational basis for the same to his target audience. For example, after the formal announcement of the Middle Way Approach Rinpoche made every effort to put His Holiness’ initiative in context. Understanding concerns in a section of the Tibetan community that looked at this as a compromise, he urged the Tibetan people to study our history to understand the significance of His Holiness’ approach. He pointed out that this 14th Dalai Lama has — through a very far-sighted approach — provided the Tibetan people in all the three provinces with the feeling of being one people once again. In order to understand its significance, we need to go back to history. While all the Tibetans were under one united Tibet at one point of time, when the Communist Chinese invaded and occupied Tibet, much of the eastern and northeastern part (what we call Kham and Amdo) had already been outside the control of the Tibetan Government in Lhasa. Therefore, the importance of the renewed feeling of common identity among all Tibetans created by His Holiness cannot be underestimated.

Rinpoche’s approach can also be seen in his testimony to the Senate Foreign Relations Committee’s Subcommittee on East Asian and Pacific Affairs hearing on the “The Crisis in Tibet: Finding a Path to Peace” on April 23, 2008. He wanted the international community not to take His Holiness the Dalai Lama’s nonviolent approach casually. Through a very deeply personal and poignant way, he conveyed the significance of His Holiness’ nonviolence strategy to the Senators. He told them, “In fact to struggle nonviolently is the most difficult struggle. …Every moment it is new dedication that we have make to remain nonviolent. And we can only do it again because of the leader that we have.” He explained this by revealing for the first time publicly “the pain that I was going through” when visiting his monastery in Tibet in 2004 (as part of the dialogue process with the Chinese Government); he found 70% of it in ruins, and visited the places where his grandmother was tortured to death and his elder brother starved to death. He added, “In spite of that, because of the leadership that His Holiness provides, because of the commitment that we have made to nonviolence, you see me all smiles with my Chinese counterparts.” He ended this part saying, “I am sharing this with you because you understand and appreciate more the path of struggle that His Holiness has led us. So please help us stay on this course, because this is not only important to us, but also important for China.” I was with Rinpoche on that trip to his monastery in Tibet and had not realized the deep internal pain that he was going through.

Following his retirement and departure from Washington, D.C. “How is Lodi?” was a constant refrain that I would hear from serving and retired officials here when I accosted them. Until now, I could respond by saying that he is spending his time writing his memoir as he sees that as something that he can put his retired life in a meaningful use in the service of the Tibetan people. Now Rinpoche is no more, but he will continue to be my inspiration.

Through this post, My respect for Bhunchung la has doubled. He has been very loyal and trustworthy for Rinpoche.

Thank you Buchung la for this wonderful tribute to Rimpoche. Tibet has lost a great leader and a diplomat.

This precious life and the message he carried is inspirational by his example in living ones life in the way of a bodhisattva and his devotion to HH Dalai Lama and the Tibetan people.

I had deepest respect for Gyari Rinpoche. He was always so kind, and asked me, at his retirement party on the Hill, to continue working for Tibet. HIs words now take on the force of a command. I have his picture on my home shrine, and continue to include him in my meditations. So saddened at his departure; may he return to see a Free Tibet!