The nomenklatura system, despite its impact on Tibetan and Chinese lives, remains obscure to the wider world. This blog post dives into the newly available data from Shigatse (Chinese: Rikaze) to reveal how party power over personnel warps China’s ability to understand those it rules. This blog post analyzes leadership in the 17 counties and one district in Shigatse prefecture-level city. For analytical purposes, Samdruptse district—the only district in urban Shigatse—is treated as a county.

Based on imperial China’s principle of “law of avoidance” in appointing and rotating regional officials assigned to nonnative jurisdictions, the CCP generally follows the norm in appointing nonnative officials to directly supervise areas under its control for compliance with central directives. Like the imperial authorities, the most trusted nonnative officials with loyalty to the center are given charge of politically restive and highly sensitive posts to co-opt and control the subnational regions.[2] In the 70 years that Beijing has governed Tibet, no Tibetan has been appointed as the party secretary of the Tibet Autonomous Region. At the county level also, Han Chinese party secretaries predominantly occupy the position.

For the CCP, maintaining control over subnational authorities down to the neighborhood level—in contrast to the imperial court maintaining control up to the county level—is a critical political imperative for regime security. Unlike the late Qing imperial bureaucracy, which had 20,000 officials in the whole of China, the People’s Republic of China has 7 million cadres in the Party and government offices to govern people down to the neighborhood level.[3] The party appoints loyal leaders for effective control and direct supervision of areas for compliance with central directives conflicting with local interests, especially those in Tibet.

Although it is usually kept a secret, the party periodically uses its discretion in publishing its nomenklatura list depending on political and strategic needs. The Chinese state media’s recent open publication of the Soviet-style nomenklatura in Shigatse prefecture-level city is believed to be in response to the need for political communications and a road map among the insiders of the large and complex bureaucracy crucial for sustaining Beijing’s rule.

Map of Shigatse in the “Tibet Autonomous Region”. Image credit: Keithonearth under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license

Shigatse is big and strategic. Sharing international borders mostly with Nepal, Bhutan and India (the southern nine out of 18 counties share international border), the land mass of Shigatse prefecture-level city (70,271 sq mi) in southwest Tibet approximately corresponds to the combined land mass of Nepal (56,956 sq mi) and Bhutan (14,824 sq mi). Like all territories under the control of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), the Leninist principles of party organization and state-society relations apply to Shigatse as well to maintain the party’s power and the domination of Chinese over Tibetans. Although the nomenklatura system allows for nominal representation of Tibetans in the government bureaucracy, Chinese dominate all the strategic party bodies with real power or are strategically embedded in bureaus where Tibetans are the majority.

Chinese domination of the county party bodies

In China’s party-state bureaucracy, the party bodies are where the power lies and the vital decisions are made. The government in charge of day-to-day work is strictly controlled and guided by the party bodies. In this light, whoever dominates the party bodies, also controls the government implementing the policy decisions.

All the party bodies in Shigatse’s county-level governance are undoubtedly dominated by Han Chinese cadres posted in Tibet. Tibetans whose expertise in local affairs are critical for the Han outsiders in developing policies are represented in positions beneath those held by the Chinese.

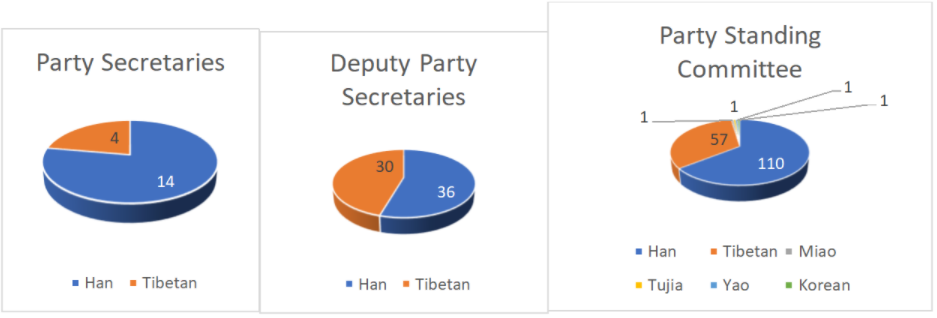

The 18 counties in Shigatse are dominated by Han Chinese dispatched to distant Tibet because they have been assessed as loyal to the party. Party secretaries take charge of political affairs and in setting strategies for their counties. Fourteen out of 18 (78%) county-level party secretaries are Chinese except for four Tibetan party secretaries in rural Panam, Ngamring, Rinpung and Khangmar counties. The deputy party secretaries in the 18 counties are also mostly Chinese, accounting for 54.5% of deputy party secretaries. In all counties there are between three to four deputy party secretaries, with one of them holding the “aid Tibet” cadre post. “Aid-Tibet” will be discussed later in this blog. Not only at the provincial, regional or municipal level, the standing committee of the CCP is the most powerful decision-making body where the seat of power lies at the county level as well. The county party standing committees are also disproportionately represented by 110 Chinese accounting for 64% of the membership, and Tibetans accounting for 33% of the total membership. The composition of the party standing committees are important for county governance and therefore carefully selected by the provincial leadership to maintain the party’s power down the hierarchy.

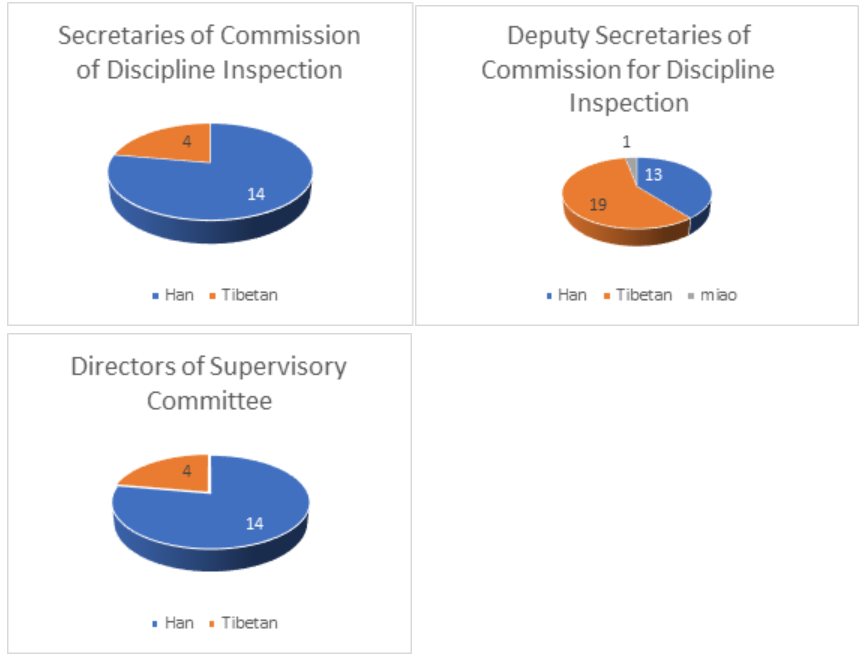

The other party entities in the Shigatse nomenklatura are also dominated by Chinese. Seventy-eight percent of the 18 county secretaries of Commission of Discipline Inspection are Chinese, whereas 58% of the deputy secretaries are Tibetans (usually a Chinese and Tibetan deputy secretary in each county). The directors of the Supervisory Committee are also dominated by Chinese at 78% or 14 out of 18 Directors.

Tibetan majority government and legislative bodies

With the policies and strategic directions set by the county standing committee of the CCP, the government oversees the day-to-day county governance work. In a party-state system, government is subservient to the ruling party. In government entities, Tibetans are well represented. It must be noted that most of the government workers also hold CCP membership, which ensures that the interests of the CCP and power override the Tibetan majority government. The governor of a county also holds the concurrent designation of the county deputy party secretary. Every Tibetan knows the party is in command, and state officials must obey.

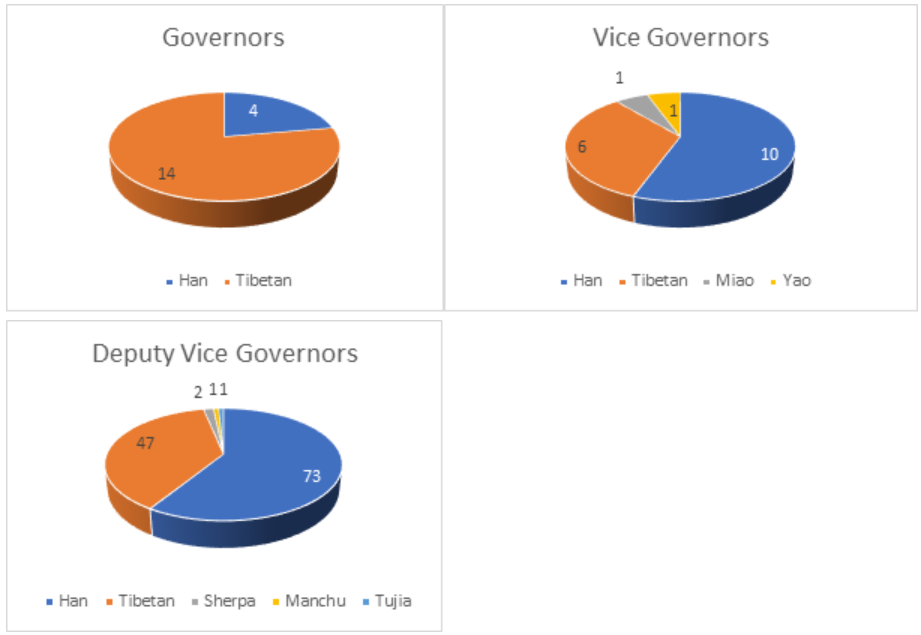

The 1984 Regional Ethnic Autonomy Law requires autonomous regions and counties to be represented by the ethnic people who are expected to be intermediaries of the Chinese state with their knowledge of the society from the inside. However, representation alone does not guarantee benevolent governance, especially when the Tibetans as intermediaries of the Chinese state are expected to give top priority to regime stability and power. Tibetans in the county government are essentially intermediaries who know their society from inside and whose mediation is relied upon for state legibility and competency. Article 17 of China’s Regional Ethnic Autonomy Law requires that “the head of an autonomous county shall be a citizen of the nationality exercising regional autonomy in the area concerned … who direct the work of the people’s government at their respective levels.” Seventy-eight percent, or 14 out of 18, county governors in Shigatse are Tibetans, whereas 56%, or 10 out of 18, vice governors are Chinese.

A Tibetan majority government headed by a Tibetan governor at the county level, like the regional level for responsive governance, does not necessarily mean a democratic or locally accountable governance. The Tibetans in the county government act as insiders and intermediaries of the Chinese state by providing their knowledge of the society, relationships, and experience in service of the party-state. Their role is implementing the hardline policies driven by the regional higher-ups, who in turn are guided by their principals in Beijing. Ethnic Tibetan cadres facilitating outsider ethnic Han-developed hardline policies and managing societal backlash against the policies is useful for the party-state regime. This state practice is like imperial China’s personnel management in the Chinese heartland. Ethnic Manchu Qing emperors ruled China and the Chinese by appointing insider and politically trustworthy ethnic Manchus as military viceroys and ethnic Han as governors with their extensive local knowledge and experience for the ethnic Manchu’s empire-state building.[4]

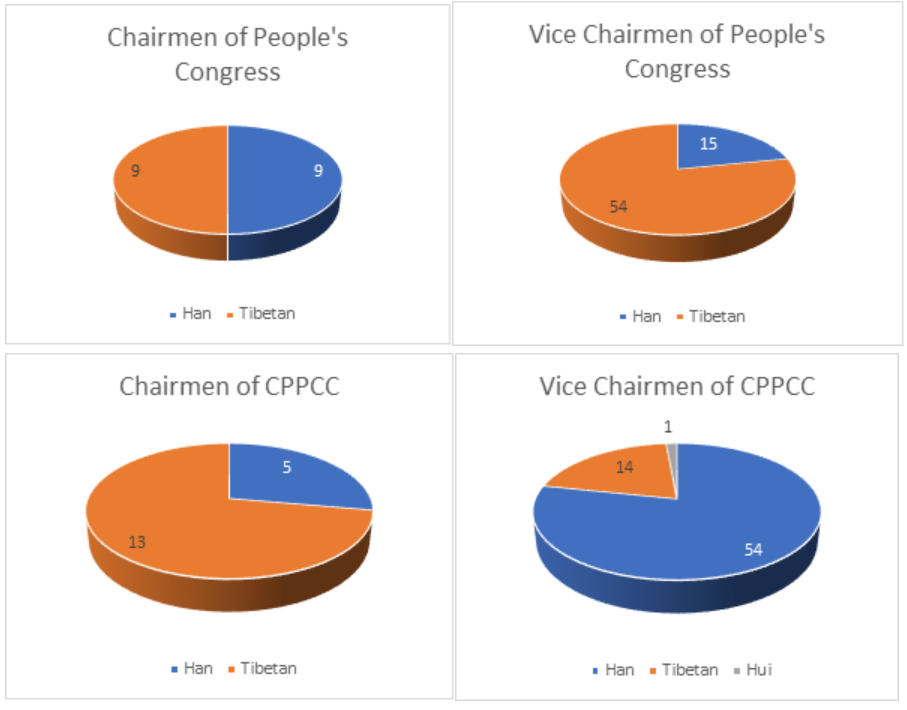

In the two legislative bodies at the county level, Tibetans also account for most of the leadership positions. Because of the constitution’s fundamental principle of democratic centralism, the congresses at the lower-level function as extensions of the central government answerable to the “unified leadership” in Beijing.

In the Chinese political system, legislative bodies hardly initiate political legislation, which is true at the center as well as at the county level. Legislatures enact the will of central leaders. However, legislation on economic affairs is relatively less constrained if the party directives are not violated. Nine (50%) chairmen of the county people’s congresses in Shigatse are Tibetan, whereas 54 (78%) of the vice chairmen are also Tibetan. The chairmen of the county Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference are mostly Tibetans at 72% in 13 out of 18 counties, while the Chinese hold 75% of the vice chairman positions, or 54 out of 69 vice chairmen of the county CPPCC.

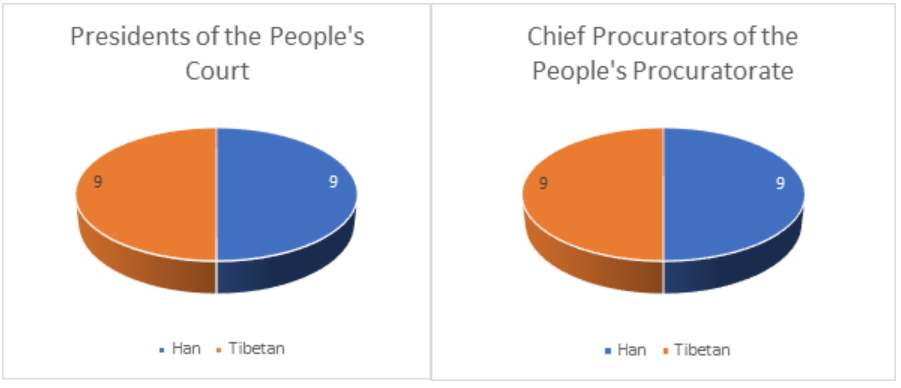

The composition of the top leaders of the Shigatse county-level legal system is peculiarly 50% for both Tibetans and Chinese. The composition is one of a perfect balance between Han Chinese and Tibetans, as in the Chinese dualistic notion of yin and yang. However, the perfect balance is only surface-level deep. The US Congressional-Executive Commission on China points out that various internal and external mechanisms limit the ability of China’s judiciary to make independent decisions. For instance, local governments interfere in judicial matters to protect local industries and to shield themselves from liability in administrative lawsuits. Since local governments appoint the judges, control their salaries and court finances, they can influence judicial decisions. The CCP approves the judicial appointments, as well as enforces party discipline in courts. The party also influences the courts through the Political-Legal Committees in the local government that influence judicial cases. The procuratorate and the people’s congresses supervise the work of judges and the courts. The procuratorate’s dual role in prosecuting and supervising the legal process makes the Chinese legal system anything but balanced and free of conflict of interest.

Counterpart assistance policy

A further complexity is added by the aid-Tibet policy that links wealthy Han Chinese cities and provinces with specific counties in Tibet. Some of the cadres sent to operate this “counterpart assistance” program rank high in the nomenklatura, as they are designated as the link for economic construction of Tibet and project implementation on the ground. In every county in Shigatse, an “aid-Tibet” cadre is present at the rank of deputy party secretary in the party hierarchy and deputy vice governor in the government. All the top 36 aid-Tibet cadres in Shigatse are Han Chinese from the eastern edge of mainland China to make Shigatse a political and economic zone favorable for Han migrants. This matters because they are answerable to the wealthy province that appoints them, incentivizing them to skew “aid-Tibet” projects to benefit their principals rather than help Tibetans to benefit from state investment, abandoning a Tibetan-first development strategy.

In 1979, the first “National Border Defense Conference” held by the central committee began the gradual institutionalization of the “counterpart support” policy replacing the arbitrary and random “assistance” and selection of cadres to Tibet in the initial years after Beijing’s occupation of Tibet. With the proposal for the state to increase capital and material input in border and minority areas, pairing of mainland Chinese provinces and municipalities to the “backward and underdeveloped ethnic minority areas” was determined as the direction of development for the “common prosperity” of China.

The third Tibet Work Forum in 1994 was the turning point in officially establishing the basic framework of the counterpart “Aid-Tibet” system replacing the previous national counterpart assistance practice of uniformly selecting cadres from the central government to work. The third Forum decided that 14 provinces and the hinterland would support 44 counties in seven prefectures and cities in Tibet. The Forum launched 62 large-scale projects in the TAR, ushering in large-scale Han migration to Tibet. In theory, they were experts who could teach Tibetans, transferring specialist knowledge to locals. The counterpart “Aid-Tibet” system was further tweaked in the subsequent fourth Tibet Work Forum in 2001 to expand the scope of projects and mainland provincial pairing to Tibet to cover all the remaining counties and districts in the TAR.[5]

Four Chinese provinces and cities and two business enterprises are primarily assigned to “assist” Shigatse. Mainland China’s Shanghai, Shandong province, Heilongjiang province, Jilin province, oil giant Sinopec and Shanghai Baosteel are involved in Shigatse’s development. Each mainland city or province takes charge of a certain number of counties in Shigatse. For example, besides Kashgar in Xinjiang and Sizhou in Yunnan, Shanghai also runs projects in Gyantse county (counterpart Pudong new area), Dhingri county (counterpart Songjiang district), Sakya county (counterpart Xuhui district), Latse county (counterpart Yangpu district) and Dromo county (counterpart Putuo district) in Shigatse. Although four out of the five counties (Dromo county is semi-agricultural and semi-pastoral), 60% of the aid funds and projects are used by Shanghai for development at and below the county level to “modernize” rural Tibet.[6]

The “Rural vitalization strategy for modernized economy” proposed at the 19th National Congress of the CCP in 2017 is now being implemented in full force with self-congratulations on “shaking off poverty” in 2020 as required by the strategy. Officially, the target was met.

Urban-rural integration is the goal in the development blueprint in the recently launched “14th Five-Year Plan (2021-2025) for National Economic and Social Development and the Long-Range Objectives Through the Year 2035.” Tightening rural governance and urbanizing rural Tibet is expected to further accelerate in the near term by further integration of Tibetan rural areas into China’s formal industries “assisted” by counterpart coastal cities and provinces.

Chinese cadres in Tibet

Securitizing Tibet, and surveilling and controlling the Tibetan population, has long been China’s top priority, with development depicted as the long-term solution. While the cadres in China’s nomenklatura system have long been considered by Beijing as the key to solving China’s Tibet problem, the cadres, and the projects they implement are unpopular among Tibetans.

The second wave of Han cadre migration to Tibet since the 1990s, although competent professionals with outstanding education from China’s top universities, has no interest in joining a conversation with the Tibetan community or learning the Tibetan language to understand the objects of their rule. The cadre turnover rate is high in Tibet, with most spending two to three years before promotion moving back to their native towns, having built up credentials for their career trajectory. Some simply resign and leave unexpectedly, unable to adjust to Tibet’s climate or for non-availability of services they are used to in wealthy urban areas. Altitude sickness is common. Although the first wave of revolutionary cadres was less educated, sent with the mission of being the proletariat class fighters, many were Chinese-Tibetan bilingual and integrated better into Tibetan society.[7]

Some of what we know comes from fieldwork research coming out of Shenzhen University. Taotao Zhao is a specialist on ethnic policy making and implementation processes in China. In her study of the cadres in Tibet, she argues that recruitment, minority cadre arrangement, evaluation and term of office have created obstacles to the cadres’ performance in Tibet. For the non-performance of the cadres, she points out that “the TAR’s current recruitment standard that targets highly professional ethnic Han cadres has attracted personnel with minimal intentions of integrating with the local community. Second, ethnic minority cadres are troubled by an identity crisis in which they are trusted neither by the local population nor their ethnic Han superiors. Third, cadre evaluation in the TAR has overemphasized social stability performance, which often overwhelms the cadres and encourages abuses of power. Fourth, the short term of office encourages cadres to pursue short-term outputs, regardless of policy outcomes, and presents challenges to the continuity of institutionalized policies.”

China’s nomenklatura system has enabled the party to maintain effective control of the state and the party’s power. However, the system does not serve the real interests of the Tibetan public except for the elite few. Yet the party is committed to maintaining the system rather than to institute an alternative system allowing Tibetans to have a say in their own lives. The party’s apparent fear of expanding the Tibetans’ participation in public affairs and decision making shut down any possibility of establishing an alternative structure of public servants. Instituting an independent watchdog to oversee and assess the cadres’ performance is also not an option. A free of conflict-of-interest watchdog would mean the party losing monopoly of its power. What remains on the ground is an institution that is imperfect, and state building continues to be a work in progress.

Shigatse nomenklatura in both Chinese and pinyin, and the percentage calculation of the cadre’s nationality at various designations is available to download here.

Footnotes:

[1] John P. Burns, “The Chinese Communist Party’s Nomenklatura System as a Leadership Selection Mechanism: An Evaluation,” in The Chinese Communist Party in Reform (Routledge, 2006).

[2] John Fitzgerald, “Cadre Nation: Territorial Government and the Lessons of Imperial Statecraft in Xi Jinping’s China,” The China Journal 85 (January 1, 2021): 26–48.

[3] Bulman, David J., and Kyle A. Jaros. “Loyalists, Localists, and Legibility: The Calibrated Control of Provincial Leadership Teams in China.” Politics & Society 48, no. 2 (June 2020): 199–234.

[5] Lei Wang and Yunsheng Huang, “Research on the Evolution and Operating Characteristics of Counterpart Assistance Policies: Taking Counterpart Assistance to Tibet as an Example,” Journal of Southwest University for Nationalities (Humanities and Social Sciences Edition), no. 39(05) (February 26, 2018). Chinese language publication.

[6] Wei Lu, Hancun Yu, and Jie Yang, “Analysis of the Association between Aided Talents and Regional Development Based on the Coupling Model: Taking Shanghai’s Counterpart Support to Xigaze, Tibet as an Example,” Rural Economy and Technology 29 (20) (July 21, 2018). Chinese language publication.

[7] Taotao Zhao, “The Cadre System in China’s Ethnic Minority Regions: Particularities and Impact on Local Governance,” Journal of Contemporary China, February 26, 2021, 1–15.