On this 30th anniversary of World Press Freedom Day, that’s one urgent takeaway from two recent reports chronicling Beijing’s subversion of the free press.

In its annual report this year, the Foreign Correspondents’ Club of China documents Beijing’s use of weaponized COVID-19 restrictions, surveillance, harassment and intimidation to stymie the work of foreign journalists in 2022. Worse, the Chinese government denied visas to foreign journalists and even kicked some journalists out of the country altogether.

At the same time, Beijing has increasingly polluted news outlets in other countries with its propaganda lies. That’s according to a 2022 report on Beijing’s global media influence by the watchdog group Freedom House, the same organization that recently rated Tibet as the least-free country on Earth alongside South Sudan and Syria.

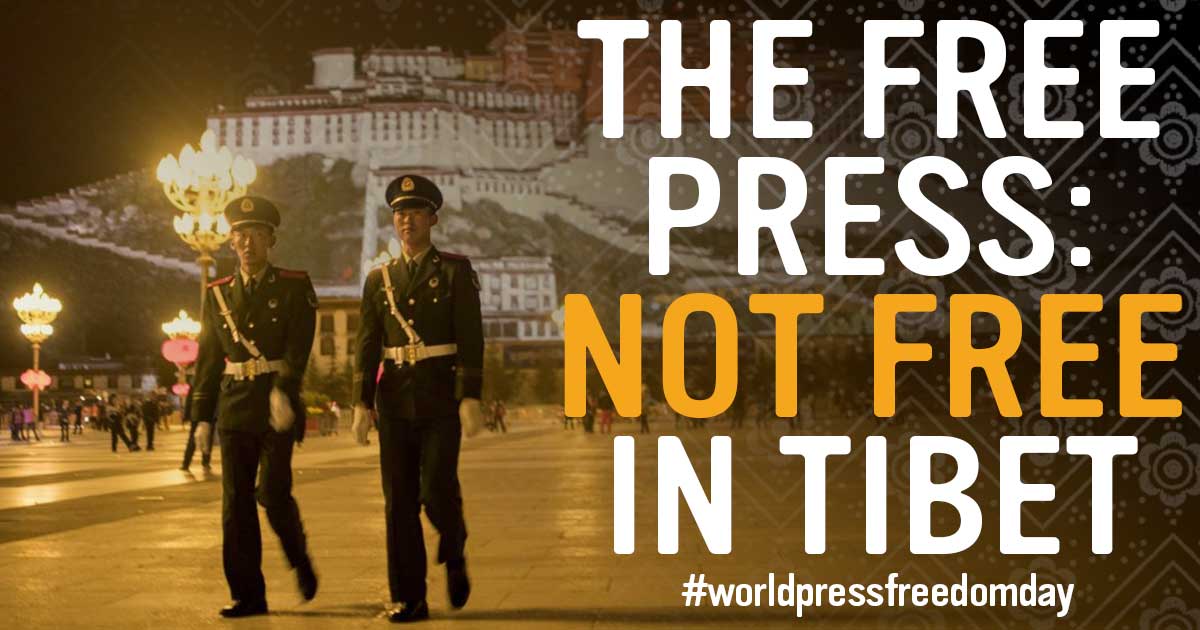

Press freedom, like most basic freedoms, is virtually non-existent in Chinese-occupied Tibet. But that hasn’t stopped Beijing from exploiting media freedom in other countries to spread its fake news about the Tibetan people.

Lack of media access

In the Foreign Correspondents’ Club report, several foreign journalists say they had less freedom in 2022 to make reporting trips around China than they did in years prior. “Perhaps the most dramatic escalation has been the tendency to be followed by carloads of officials almost every time we report outside Beijing,” says the BBC’s Stephen McDonell. “Apart from harassing journalists, they intimidate and pressure those we are trying to interview.”

But one area where no escalation was needed is the so-called “Tibet Autonomous Region.” That’s because foreign media have long been denied access to the TAR, which spans most of western Tibet.

The TAR is the only region that the People’s Republic of China requires foreigners, including journalists, to get special permission to enter. “Access to the Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR) remains officially restricted for foreign journalists,” the club’s report says. “Reporters must apply to the government for special permission or join a press tour organized by China’s State Council or” Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

However, those press tours are organized to keep journalists from seeing the truth about China’s oppression of the Tibetan people. And the special permission journalists must get is rarely if ever granted.

In the Foreign Correspondents’ Club’s annual survey, three journalists said they applied to visit the TAR in 2022. All three were denied. Even those who were able to visit other Tibetan areas outside the TAR faced restrictions.

No longer trying

Perhaps even more disturbing is the fact that so few journalists appear to even be trying to enter the TAR anymore. In 2021, four journalists in the club’s survey said they applied for permission to visit the region; all four were denied. In 2018, there were five applicants and five rejections.

The fact that even this small number has diminished over the years suggests that individual journalists don’t think it’s worth applying because they know they’ll never be accepted. Thankfully, higher authorities have taken up their cause.

In 2019, the Foreign Correspondents’ Club published a position paper calling on China to allow journalists “unfettered access to the Tibet Autonomous Region and all Tibetan-inhabited regions.” The paper adds that foreign governments should protest China’s intimidation of journalists who interview the Dalai Lama and request data from the Chinese government on journalists’ applications to report on Tibet.

The paper followed the passage of a pathbreaking US law, the Reciprocal Access to Tibet Act. Known as RATA, the law pressures China to give US journalists, diplomats and ordinary citizens the same level of access to Tibet that their Chinese counterparts have to the United States. Under RATA, the State Department has banned entry to the United States by Chinese officials involved in keeping Americans out of Tibet.

What happens in Tibet doesn’t stay in Tibet

RATA became law in 2018, the same year I joined the International Campaign for Tibet. During my time as ICT’s communications officer, I’ve spoken to several journalists who have tried to visit Tibet for a reporting trip but were physically stopped by Chinese authorities.

Given these experiences, I can understand why some journalists might give up on ever trying to enter Tibet. But Tibet’s story needs to be told.

For one thing, the Tibetan people deserve to have their voices heard around the globe. For more than 60 years, they have lived under one of the world’s most brutal occupations. China has routinely violated their basic freedoms, including religious freedom, freedom of movement and, yes, freedom of the press. In this bleak landscape, it’s not surprising—but nevertheless tragic—that over the past 14 years, nearly 160 Tibetans have self-immolated, lighting their own bodies on fire in a desperate act of protest.

However, it is not just Tibetans who suffer from this repression; as much as China keeps a tight lid on Tibet, what happens there doesn’t ultimately stay there. Beijing’s brutalization of the Tibetan people has spread to other territories under its command, most notably Xinjiang, which Uyghurs know as East Turkestan. China’s genocide of the Uyghurs was initially led by Chen Quanguo, who honed his vicious tactics as the Chinese Communist Party Secretary of the TAR from 2011-2016.

Now, China’s repression in Tibet is fueling Beijing’s repression in other parts of the globe, including here in the United States. I am not just talking about direct threats and transnational repression against Tibetan activists in exile. I also mean China’s efforts to censor the truth about Tibet, spread disinformation and fool media consumers into believing its lies.

State media inside the free media

As Freedom House’s “Beijing’s Global Media Influence Report 2022” states, the “Chinese government, under the leadership of President Xi Jinping, is accelerating a massive campaign to influence media outlets and news consumers around the world.” The report adds: “The possible future impact of these developments should not be underestimated.”

While China has long sought to warp global public perception in its favor, according to the report, its efforts increased starting around 2019, when Beijing began to suffer the bad press of its crackdown in Hong Kong, its genocide of the Uyghurs and its attempted coverup of the origins of COVID-19, among other issues.

Rather than try to mitigate this public relations disaster by, say, telling the truth about COVID or respecting the rights of Uyghurs and Hong Kongers, China instead tried to muscle the media into submission. It did this via several methods.

One of Beijing’s primary tactics has been to place content made by or friendly to the Chinese state in news outlets around the world, including print, TV, internet and radio news. Such content appeared in

over 130 news outlets across 30 countries studied in Freedom House’s report. “The labeling of the content often fails to clearly inform readers and viewers that it came from Chinese state outlets,” the report says.

Through these placements, Beijing is able to reach a much wider overseas audience than its own state media would allow. And it can do so without having those audiences know clearly that they are receiving CCP propaganda. Worryingly, China appears to be aggressively pursuing more of such placements in foreign media outlets. Coproduction arrangements in 12 countries allowed China to have a degree of editorial control over reporting in or on China in exchange for providing the foreign journalists with technical support or resources.

China has also resorted to blatant bribery. According to Freedom House’s report, CCP agents offered monetary compensation or gifts such as electronic devices to journalists in nine countries, including Kenya and Romania, in exchange for pro-China articles written by local journalists.

Intimidation of journalists, including Tibetans

Then there are China’s attempts to censor foreign journalists. According to the report, Chinese diplomats and government representatives intimidated, harassed and pressured journalists and editors in response to their critical coverage, at times demanding they retract or delete unfavorable content. The Chinese officials backed up those demands with implicit or explicit threats of defamation suits and other legal repercussions; a withdrawal of advertising; or harm to bilateral relations.

Sadly, those demands have at times been successful. In one glaring example, in August 2021, China’s embassy in Kuwait pressured the Arab Times to delete an interview with Taiwan’s foreign minister from its website after the interview already appeared in print. The interview was then replaced by—and this is not a joke—a statement from the embassy itself.

Even more sadly, journalists from communities that Beijing oppresses—including ethnic Chinese dissidents—have been the target of some of China’s most coercive attempts at overseas censorship. Last year, Erica Hellerstein reported in Coda that a Tibetan exile journalist in an unnamed country was tricked into meeting with a Chinese state security agent who appeared to make vague threats about the journalist’s family members still living in Tibet. A few weeks later, a group of men ambushed the journalist as he walked home, throwing a black bag over his head and forcing him into a van that drove around for hours as the men grilled him for information and searched his phone.

The journalist reportedly quit his media career after that, fearful of what would happen to his relatives in Tibet if he continued his important work.

Social media spread

It’s not just the traditional media that Beijing is preying on; it’s also social media. According to Freedom House’s report, Facebook and Twitter have become important channels of content dissemination for China’s diplomats and state media outlets. However, these state actors are not attracting attention via organic interest. Instead they are purchasing fake followers and using other tools of covert manipulation.

As Freedom House states:

“Armies of fake accounts that artificially amplify posts from diplomats were found in half of the countries assessed. Related initiatives to pay or train unaffiliated social media influencers to promote pro-Beijing content to their followers, without revealing their CCP ties, occurred in Taiwan, the United States, and the United Kingdom. In nine countries, there was at least one targeted disinformation campaign that employed networks of fake accounts to spread falsehoods or sow confusion.”

One of Beijing’s most noticeable—and unfortunately most successful—targeted disinformation campaigns has been its deliberate amplification of an edited video clip of His Holiness the Dalai Lama interacting with a young boy in India. The clip, which takes the interaction out of its cultural context and suggests lurid intentions where there were none, went viral over a month after the interaction took place, thanks to suspicious accounts that appeared out of nowhere and helped get the clip coverage in major news outlets.

Disinformation and disbelief

It’s important to note that according to Freedom House’s report, Beijing’s influence campaigns have had mixed results so far. The CCP has failed to get its official narratives and manufactured content to dominate coverage of China in the 30 nations studied in Freedom House’s report. And domestic journalists, civil society groups and governments in the 30 countries have been at least somewhat effective in pushing back on Beijing’s efforts at manipulation.

However, I can’t help but feel concerned about Beijing’s potential for long-term success. On this 30th World Press Freedom Day, the press is in tough straits. Layoffs and closures have ruptured the industry. Vice, which provided some of the fairest, most informative coverage of the aforementioned controversy surrounding His Holiness, apparently gutted its Asia-Pacific news desk and may be preparing for bankruptcy.

As the financial void in journalism grows, China is positioned to step in with bags of money. As Freedom House notes, “As more governments and media owners face financial trouble, the likelihood increases that economic pressure from Beijing will be used, implicitly or explicitly, to reduce critical debate and reporting.”

This softening of the traditional media model comes with public trust already on the decline. As I wrote in a previous blog post, contrarians and charlatans are spreading conspiracy theories that catch fire among the alienated in society. And now the Chinese government is working even harder to sow division. As Freedom House says, Beijing’s campaigns have “reflected not just attempts to manipulate news and information about human rights abuses in China or Beijing’s foreign policy priorities, but also a disconcerting trend of meddling in the domestic politics of the target country.”

On this World Press Freedom Day, we must find ways to buttress free and independent media from China’s attacks, including perhaps by allotting more government and philanthropic funding to journalists. And we must use our own freedom of expression to call out the double standard that allows Beijing to block foreign media from its country while barraging other countries with its fake news.