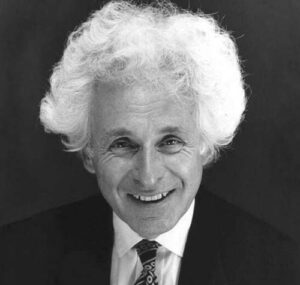

Jerry Mander

In this year of climate disasters and artificial intelligence, a future of ecological and technological destruction feels as inevitable as the April death at age 88 of the author quoted above. But looking back at his writing, I’m convinced we needn’t accept such inevitability.

Jerry Mander (yes, that was his real name; no, he had nothing to do with election rigging) was an activist and advertiser for environmental causes. He’s best known for writing 1978’s “Four Arguments for the Elimination of Television,” a weighty treatise that lays out why, in Mander’s view, “television and democratic society are incompatible.”

Even 45 years ago, arguments against TV probably felt as quaint as arguments against mobile phones do today. But Mander had a knack for inspecting our casual acceptance of technology, investigating its ramifications and offering alternatives. We should get rid of television, he says, because of its (1) mediation of experience, (2) colonization of experience, (3) effects on the human being and (4) inherent biases. If you want to know more, I highly recommend reading the book.

Struggles of ‘native’ people

Mander advances his arguments in 1991’s “In the Absence of the Sacred: The Failure of Technology and the Survival of the Indian Nations.” This time, he broadens his aim to target not just TV but also computers and space travel. However, about halfway through the book, Mander pivots from critiquing technological society to hailing “Indian” (by which he means Indigenous) alternatives. That’s where Tibet comes in. (Disclosure: I’ve read “Four Arguments” in full but have not yet finished “In the Absence of the Sacred.”)

Mander, an American, focuses mainly on Native Americans. But in a later section of the book, he surveys the struggles of Indigenous people around the globe. About Tibetans living under China’s occupation, he writes:

The most well-known of today’s conflicts [between the Chinese government and “minority” groups] is taking place in Tibet. Chinese armies invaded Tibet in 1950 … Since then more than one million Tibetans have died resisting the invaders. In an open effort to forever suppress the elaborate and celebrated Tibetan culture, the Chinese have destroyed more than 6,000 monasteries, which also housed most of the Tibetan nation’s art, religious artifacts, and books.

I can imagine some of you shaking your head right now. A lot of Tibetans reject the “Indigenous” label, although some in the younger generation have embraced it (here’s a good explainer). Moreover, people like Mander, who exalt Indigenous cultures, risk promoting “noble savagery,” the belief that Indigenous people lived in a state of perfect nature before they fell under the control of “civilization,” a claim that critics deride as racist and ahistorical.

On the other hand, the Chinese government uses the opposite argument—that Tibetans are backward and in need of development—to justify its forced resettlement of Tibetan nomads and despoilment of the Tibetan Plateau. Unfortunately, even we Tibet supporters in the West can fall victim to this mindset due to the inherent biases of our “modern” world.

Myth of progress

There’s no doubt Beijing and the West have different visions of the future. But both are plagued by a myth of progress. This is the belief that change is necessary, beneficial and inevitable. According to this view, things are perpetually getting better. Hatred and bigotry are fading away; poverty and disease are disappearing; violence and war are vanishing from the Earth. At the same time, people are growing smarter and more tolerant, while technology carries us toward a paradisaic future. (In the Chinese version, there may be less emphasis on social justice, but the narrative of continuous improvement is still there.)

This belief has been a driving force of the West for ages. It was used to justify America’s own abhorrent colonization of native lands, and I think it lingers in our collective unconscious. But over the past few years, with the emergence of COVID-19, the eruption of war in Ukraine (not to mention all the wars happening in non-White places) and the return of fascism, it’s not so easy to believe in the march of progress anymore. (To his credit, Mander rejected this eschatology even during the boom times of the post-World War II era and the “end of history” period when the Soviet Union fell and liberal democracy looked destined to reign forever.)

My disenchantment with progress is partly why I joined the Tibet movement in 2018—because I believed that Western progress, rooted in the destruction of nature and alienation of people, was driving us off a cliff, and we needed alternatives from different traditions. As a result, I’m still a bit wary of using Western institutions and concepts like individual rights to defend Tibet from China’s predations, even though I recognize the usefulness of doing so. To me, that’s akin to expecting technology to save us from the problems technology has created.

I think it would be a mistake to frame our goal of liberating Tibet as the triumph of progress against the darkness of Chinese authoritarianism. I have no say in the matter—and as a non-Tibetan, I don’t deserve one—but to me, it would be a shame if a free Tibet ended up like just another cog in the liberal order, with a veneer of cultural difference but ultimately the same beliefs and same problems as the contemporary West. I don’t know what the future Tibet should look like, but I hope it will look better than what we have in the US today.

Things don’t have to change

That gets me back to Jerry Mander. In one of my favorite passages so far from “In the Absence of the Sacred,” he describes speaking with Oren Lyons, faithkeeper of the Turtle Clan, Onondaga Nation, who explains to Mander the Iroquois governance system. Far from the despotic chiefdoms that Native Americans are stereotyped as living in, the Iroquois instead had a democracy purer and more participatory than the “representative democracy” other Americans have.

Rather than majority rule, the Iroquois required consensus for decision-making. At council meetings, all adults had the right to speak, so long as they did not speak too loudly or try to dominate others. And the discussion would take as much time as needed. (Mander writes, “Lyons added that only in machine-oriented societies is there pressure to get human matters processed quickly, because society is moving at machine-speed.”) If three meetings went by without a consensus, the issue would be dropped. “We figure it will come up again some other time,” Lyons says.

Mander writes:

At first I was shocked by this idea of just dropping something that cannot be agreed upon. But eventually I realized that the Indian decision-making system is biased toward the idea that things don’t really have to be changed. They can stay the way they are. If some step really is needed—say there’s an attack of some kind—then a consensus will be reached and steps will be taken. The equivalent principle in American terms is “If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.”

Save Tibet

Unfortunately, too many of us moderns, me included, are still trying to fix things that aren’t broken. We continue to adopt (or are coerced into adopting) new technology, from the smartphone a decade-and-a-half ago to generative AI today. The problems these technologies supposedly solve are generally made-up or not really problems at all—our species survived without an iPhone for 300,000 years after all—and whatever good they do is overwhelmed by the enormous harms they fuel: the destruction of the climate, the subversion of democracy, the crisis of mental health, the concentration of wealth and power, the rise of hate movements and the descent of humanity into a post-human future. If progressives really want the things they say they want, they might do better to turn the clock back on technology rather than forward.

The acceptance of these “innovations” is based in part on people’s belief in their inevitability—that even if we don’t want them, we have no choice but to assimilate. Adapt or die. That same belief shaped the attitude toward television decades ago. But one key takeaway from Mander’s books is that we don’t have to accept things we don’t need. We can choose to reject change that will subtract more than it adds.

When it comes to Tibetans, they don’t have to become Chinese. They don’t have to become Western, either. If they need to change—and the Dalai Lama himself has been a staunch reformer—they deserve the freedom to discuss and decide that for themselves.

As Mander writes, Tibetans “are considered among the world’s most refined people, psychologically, socially, spiritually, and artistically.” So rather than sail on to the next techno-utopia after trashing this continent and leaving it behind, we should seek to preserve the Tibetan civilization that China is trying to toss on the ash-heap of history. True progress isn’t colonizing Mars; true progress is saving Tibet.

One last thing: Carmen Kohlruss recently wrote a lovely piece for Tricycle magazine about the connection between Tibetans and Native Americans in western Montana. Check it out.

I appreciate the effort; – really I do. But I’m reading such a mish-mash of ideas, framed with poorly understood wokeisms, that I’m at a loss for words. The CCP loves to invoke the genocide against American Indian tribes as justification for the CCP’s brutality against Tibet & Tibetans. But it’s a false equivalency. The CCP should have learned better. So the sad reality now, is that the old Tibet is under Han Chinese subjugation. Over 1,000,000 Tibetans have fled for their very lives, to countries all over the planet. That means that the WHOLE PLANET EARTH, – minus China & Tibet, is now FREE TIBET….