A research attempt into China’s visa practice, transnational repression and the limits to overcome the fears in Tibetan diaspora

By: Simon van Dongen

I am a Dutchman who is fascinated by Tibet, because of its nature and culture. A country with a two-thousand-year-old history, situated on a plateau with an average elevation of 4500 meters above sea-level. Today, Tibet is a highly restricted area. I have never been there, and I will probably never go there. Instead of travelling to Tibet I went to Nepal. Over there I met people from the Nepalese Himalayas who share Tibetan heritage. They are called Sherpa. Calm and warm people. There, in Langtang National Park, I had my first encounter with Tibetan culture.

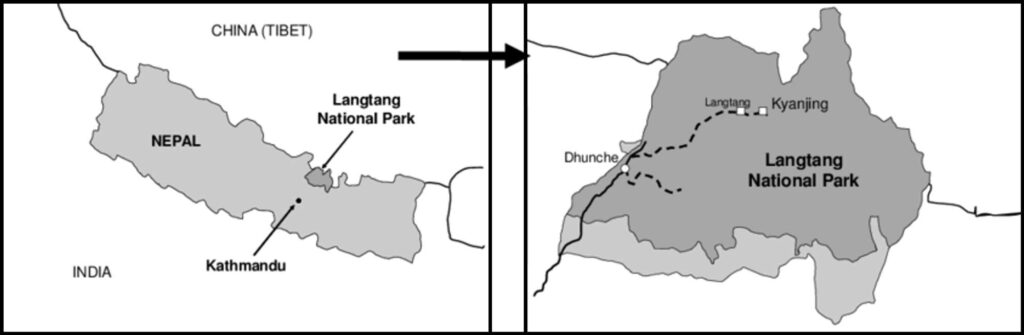

It was a long journey. Although it looked nearby on the map, it took 7 hours to reach Langtang National Park from the capital Kathmandu. This narrow mountain dirt road was a horrifying experience. Eventually, I arrived at Dhunche, which is close to the Tibetan border and the starting point for a major trekking route. The road I took is portrayed on the map below.

Walking up the Langtang valley was like walking in a different world for me. Coming from a country below sea level, I was now walking between the highest mountains on earth. As shown on the map, I walked from a place near Dhunche towards Kyanjing. On the third day hiking, near Langtang village, I helped planting potatoes at a local farm. A picture I made that day is shown here. This intercultural interaction felt very special, partly because it all happened at an altitude of around 3500m.

Just before my travels, I finished my Human Geography thesis at Utrecht University: The flip side of the Chinese expansion of Tibet. Also, I read the biography of the former Tibetan political prisoner Palden Gyatso. Because of these documents, it became obvious to me that China has a full grasp on Tibetans within Tibet. After everything I had learned about Tibet, I realised that on the other side of this mountain in Langtang Valley, the Tibetan culture is eradicated.

A major part of my knowledge about Tibet I retrieved from two interviews during my thesis research. I interviewed Tsering Jampa and Wangpo Tethong, respectively the former and the current executive director of the “International Campaign of Tibet (ICT) Europe”. They predominantly spoke about repression within Tibet, but also mentioned Chinese transnational repression of Tibetans in the Netherlands. How and why does China repress people in my country? My curiosity around this question kept on triggering me after my trip to Nepal. This made me want to take action and return to the ICT to apply as a volunteer.

Tibetan anxieties form obstacles too high

Wangpo Tethong is a 61-year-old ICT director who came to the Netherlands two years ago. He gave me a warm welcome at the ICT office in Amsterdam. We realised that we wanted to add to the recent research: Chinese Transnational Repression of Tibetan Diaspora Communities of ‘The Tibetan Centre for Human Rights and Democracy’ (TCHRD). Although this research provides proof of transnational repression on Tibetans, I think it gets too little attention. After a discussion with Wangpo, I decided to try to create context around this subject in the Netherlands specifically.

The story of journalist Marie Vlaaskamp in De Volkskrant added to my concern about transnational repression. Chinese police in the Netherlands used intimidation to silence her critical view on China. Within this newspaper article she exposed these acts. I realised the Chinese intimidation not only impacts Tibetans and Uyghurs in the Netherlands but also journalists. While this scared me, I still felt the urge to research transnational repression.

Wangpo Tethong introduced me to Dawa Tsering, former president of the Tibetan community in the Netherlands. He fled from the Chinese occupation in Tibet when he was a child. We had a long discussion about potential research. The three of us came up with a plan for a small case-study on Tibetans in the Netherlands. By analysing what happens when Dutch Tibetans apply for a visa to travel to Tibet, we were hoping to provide proof of transnational repression of Tibetans in the Netherlands.

Dawa Tsering spoke about Chinese intimidation he experienced while applying for a Visa for Tibet. He was also invited to Brussels, where he spoke to the audience in the European parliament. I quote from Dawa Tsering’s speech on Novembre 30th 2023:

“I feel like I am being watched constantly and every step of me is being tracked. It is a scary thought to think about how much they actually know about me and my family and what they could do to us.”

I was optimistic about conducting research to uncover more of these Chinese intimidation stories. However, Dawa Tsering warned us about difficulties we would face when trying to interview Tibetan people. He explained that most Tibetans in the Netherlands will not speak up about the Visa application.

“While now, most of us are being denied a visa, it is not clear why some people do get visas and others do not. This unclarity intensifies the worries amongst Tibetans to come under the attention of the Chinese government. It might mean that they will not ever be able to return to Tibet and see their family again.”

According to this quote from Dawa Tsering, Tibetan people are scared to attract attention of the Chinese government. This is especially the case when people still want to visit their family in Tibet. Because of this, Wangpo proposed to search for Dutch Tibetans who do not have aspiration to travel to Tibet, nor have family over there. Although we searched for these participants, we did not find anyone as people were unwilling to speak for different reasons. Some Tibetan people were interested to apply for a visa and talk about the process at first. Later, they turned down the request to speak with us. This process was food for thought for me. How is it possible that virtually no one wants to talk about this?

New visa types leave doubts unanswered

To illustrate the problem, it is important to know the context about visa applications for Tibet. To gather information about documents required to travel to Tibet, I read the ICT-report “Access Denied”, I searched on the web and talked to travel agencies and a tourist who went to Tibet. Additionally, I used some of the knowledge I gathered during my thesis to provide context

If someone in Europe wants to travel to Tibet as a tourist, they only need a Tibet-permit if they stay shorter then 15 days. This is a trial policy announced by the Chinese government for visitors from six European countries, including the Netherlands. This policy was introduced on the first of December 2023 and will last a year. In order to stay longer then 15 days, tourists also need to apply for a visa at a Chinese consulate. The permit is provided by the tourists’ travel agency. If you have patience, you can deal with the restrictions and have a deep pocket, you can travel to Tibet as a Tourist.

It appeared like China has adopted a liberal tourist policy. However, travels through Tibet are regulated by China. On top of that, a fake reality is portrayed to these tourists. Tourists are only allowed to go to specific locations where they often see actors imitating Tibetan culture. These aspects make me strongly doubt the liberalism in Chinese tourist policy.

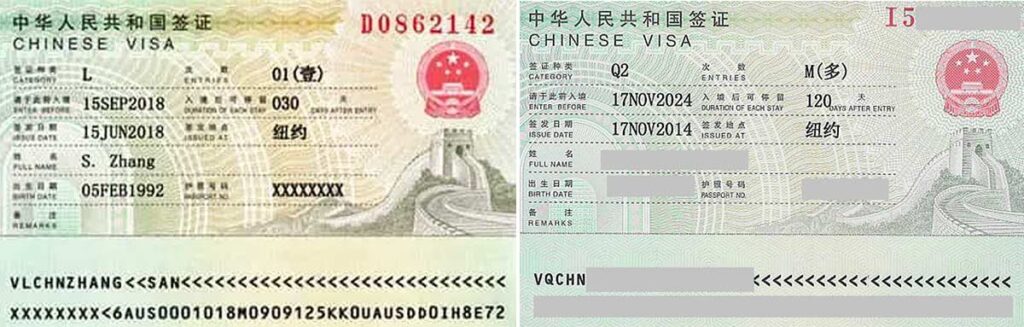

From what I have learnt, European citizens with Tibetan heritage experience way more difficulties in applying for a visa to travel to Tibet than people without. This is because they are limited to apply for the family-visit-visa. This type of visa comes with two extra conditions, namely an interview at the Chinese consulate and Chinese surveillance.

The two mentioned visa are shown here. (Left: tourist visa; Right: family-visit visa)

In the next part some stories of Tibetans applying for a visa to travel to Tibet will be given.

The ICT office in Brussels conducted a survey online in 2019. Tibetans were asked to anonymously tell their stories about their visa application for Tibet. Most of the respondents were Belgian Tibetans. One of these people explained the following about their visa application:

“My interview was around 25 minutes. The interview was all about my past and present life. I applied in Brussels Chinese visa application Center. They have asked about His Holiness the Dalai lama and his political perspective.”

So, the Chinese officials are gathering personal information, which I think they can use against you. Additionally, if an applicant says one critical thing about China, the visa will most probably not be given. Another Belgian respondent provided the following statement to the ICT:

“They asked me my birthplace and I answered them “Tibet”. Immediately they changed the visa form in English to Chinese. Then I had to give them all the information of my family members and I need to have introduction of to whom I want to visit and need two invitation letters… (…) Finally they denied to give me visa”[1]

Even after sharing the required invitation letters from family in Tibet and sharing personal details of family members, this person is still denied access to Tibet.

Of course, I would like to speak to people like from the last quote. Unfortunately, visa application volunteers were not available. A few weeks ago, Vincent Metten, EU Policy Director at ICT, told me the situation in Belgium is comparable:

“… you said Tibetans were not willing to speak and so on. (…) I think that’s also something we face in Belgium because there is a lot of prudency, people don’t want to have an impact on their chances to visit their families and friends in the future.”

ICT Europe’s EU Policy Director Vincent Metten, who conducted the online survey, says ‘there is a lot of prudency” among Tibetans in Belgium to speak up about their visa application. Some awareness about the situation was created in 2019, but because of the pudency not much information has come out since then.

Some Tibetans who want to return to Tibet restrain from speaking up against China because they fear that their visa application will be denied. During the application process China can surveil Tibetans abroad and keep them quiet. Eventually most Tibetans abroad are not granted a visa. China presents itself as liberal with their 14-day free visa period, but to me this is just a sham.

Intimidation is effective

While trying to uncover what Chinese actions caused intimidation of Tibetans, I realised that the intimidation is the reason that it is not uncovered. It is painful to admit, but intimidation as a means of transnational repression by China is effective. Tibetan voices all over the world are silenced because of it. Although stories about Chinese transnational repression are exposed by the TCHRD and the ICT, the subject does not get the attention it deserves.

Personally, it feels very unfair that Tibetans cannot access their homeland freely. I was lucky to experience the mountain culture and nature near the Tibetan border. With that in mind, I try to imagine how painful it is for the Tibetan diaspora to see this all be locked away by China. The Chinese border does the same thing as the visa constrains do; it breaks up Tibetan families. Nevertheless, during my time as an ICT volunteer I experienced the strong sense of community in the Tibetan diaspora. To me, this is pure inspiration and a sign of resilience.

Footnote:

[1] Some spelling adjustments were made to make it more readable

* The author is an ICT volunteer. He tells the story how he tried to find evidence of Chinese interference and intimidation of the Tibetan community in the Netherlands