The water-village in Melle, France.

From July 16 to 21, the small village of Melle in the Deux-Sèvres region of France hosted a water village aimed at challenging mega-basin projects and the current agricultural model.

Protests against “mega-basins”

‘Mega-basins’ are huge open-air water reservoirs, over 70% of which are financed by public funds, and most of which pump water from underground aquifers.

A mega-basin in France.

According to the NGO Les Soulèvements de la Terre, a mega-basin refers to structures of over 50,000 cubic meters and/or more than one hectare in size. Mega-basins are different from hill reservoirs, which are filled by runoff and are more modest in size. These are ponds or puddles, used by less water-hungry farmers. But hill reservoirs can also be contested, particularly in the Alps, where they are used to produce artificial snow.

There is no official record of the exact number of mega-basins in France. So there’s a lot of mystery surrounding their number!

According to the independent investigative media Reporterre, the most reliable figure concerns the former Poitou-Charentes region, comprising the departments of Deux-Sèvres, (where the water village was installed) Charente-Maritime, Charente and Vienne. Nearly eighty-seven mega-basins are planned, all of which are the subject of legal challenges. Thirty-four have been cancelled thanks to the mobilization of associations.

According to Reporter’s estimates, based on information from Bassines non merci, nearly 300 mega-basins are planned throughout France. The real figure could be higher. An interactive map shows their location and characteristics.

This water issued from these mega-basins then benefits just 5% of French farms, and is used to boost the productivity of water-hungry crops (such as maize) that are ill-suited to climate change.

More than 120 environmental, farmers’, trade union and collective organizations mobilized to call for a nationwide halt to the construction and operation of the basins, and for an immediate moratorium.

Protests against mega-basins on 19 July and 20 July.

Protests against mega-basins on 19 July and 20 July.

This mobilization, which was followed by two major demonstrations on July 19 and 20, is the third of its kind, once again firmly supervised and repressed by the security forces. The previous two were held in 2022 and 2023 in the same region. The March 2023 demonstration against the Sainte Soline mega-farming project remains infamous for the scale and virulence of the police repression that befell the demonstrators (see the Reporterre report, Sainte-Soline, Autopsie d’un Carnage).

An international dimension of the water village

The village was attended by several thousand people, including some forty guests from abroad (India, Brazil, Colombia, New Caledonia…). Swedish activist Greta Thunberg was also present, albeit discreetly. The village thus had an international dimension, which was reflected in the many debates, meetings and screenings organized throughout the event.

Some of the guests from foreign countries reading a statement of support.

ICT was invited to take part in two events at the Water Village. Firstly, I was able to speak about the mining situation in Tibet as part of the discussion on “Investigating water, extraction and the energy transition”. It brought together a fine line-up of speakers from the academic world and NGOs such as:

- Célia IZOARD: journalist and philosopher, author of La Ruée minière au XXIe siècle : enquête sur les métaux à l’ère de la transition (The mining rush in the XXe century: an investigation into metals in the age of transition),

- Claire DEBUCQUOIS; Fédération nationale de la Recherche Scientifique (FNRS research fellow),

- Juan Pablo GUTIERREZ: ONIC delegate and member of the Yukpa people affected by an open-cast coal mining mega-project, Colombia,

- and numerous collectives in struggle: No Cav against marble quarries in Tuscany, Italy, Ende Gelände against kohl mining activities in Germany, the collective in struggle against the lithium mine in Allier in France, Stop Micro 38 in France…

All these testimonies converge to demonstrate that the current capitalist system, driven by greed for natural resources, is the main driving force behind the proliferation of these destructive mining and industrial projects across the planet. In all the examples cited, the quest for profit, particularly for the large multinationals, take precedence over human rights.

Large dams: how to put an end to these weapons of domination?

ICT also spoke on a panel entitled “Large dams: how to put an end to these weapons of domination”. In addition to ICT, the panel included three speakers: a representative of the association SOS Loire vivante and Paula Davoglio Goes of the Movement of People Affected by Dams in Brazil. The presentations demonstrated that the problems associated with dams are very similar from one country to the next. These projects are generally imposed from the top down without any involvement or consultation with local populations, and often inflict serious impact on the life and culture of the populations concerned, as well as on the environment.

ICT’s participation in the panel on dams.

In Brazil, for example, which has some of the largest dams in the world (second only to the Three Gorges), some dams have burst, such as the Brumadinho dam in January 2019, resulting in the death and disappearance of 270 people. The Vale mining group had not informed the authorities of any anomaly suggesting that the disaster could have been avoided.

In 2015, for the COP21 in Paris, ICT published a report on water “Tibet’s water and global Climate Change” which addressed the issue of dams. Today, ICT’s research continues to study hydropower projects in Tibet, either completed or underway (there are said to be around 200). Evidence shows that one of Beijing’s objectives is to turn Tibet into an energy exporter, initially supplying central and eastern China as part of the West-to-East Energy Transmission Project, and then neighboring countries in Southeast Asia.

Risks of hydroelectric projects

As highlighted by an ICT news report in April this year, dams entail serious inherent risks for the local environment and its inhabitants. Three risks stand out:

- Hydroelectric dams are sensitive to and increase the risk of earthquakes, landslides and flash floods, particularly in seismically active regions such as the Himalayas.

- Dams are not environmentally friendly. They increase the human footprint in fragile and biodiversity-rich ecosystems, and interrupt essential aquatic life, soil and nutrient flows downstream. As well, the reservoirs created by land flooding also produce methane pollution, a potent greenhouse gas.

- Dams also lead to the eviction of inhabitants from their traditional homes. Residents are often forced to leave, or forced to do so without consultation, and those displaced receive inadequate compensation or have no access to a fair procedure to seek redress for the damage they have suffered.

Dams in Tibet can certainly be seen as tools of domination both over the local population and the environment, but also more broadly over relations with neighboring countries. For example, along the Yarlung Tsangpo, which becomes the Brahmaputra, dams and other large infrastructure projects are used to lay claim to disputed territories on the border with India. They literally consolidate their territorial claims. India is wary of this situation and is also stepping up infrastructure development in the north of the country.

A threat to cultural heritage

To illustrate the impact of dams on cultural heritage, the water village screened the excellent documentary “La bataille du Côa, une leçon portugaise” (The Battle of the Côa, a Portuguese lesson) in the presence of director Jean-Luc Bouvret, about the resistance against a dam project in Sao that threatened to cover Paleolithic engravings over 20,000 years old. This mobilization, led by the schoolchildren, eventually paid off, and the state had to back down and halt construction of the dam.

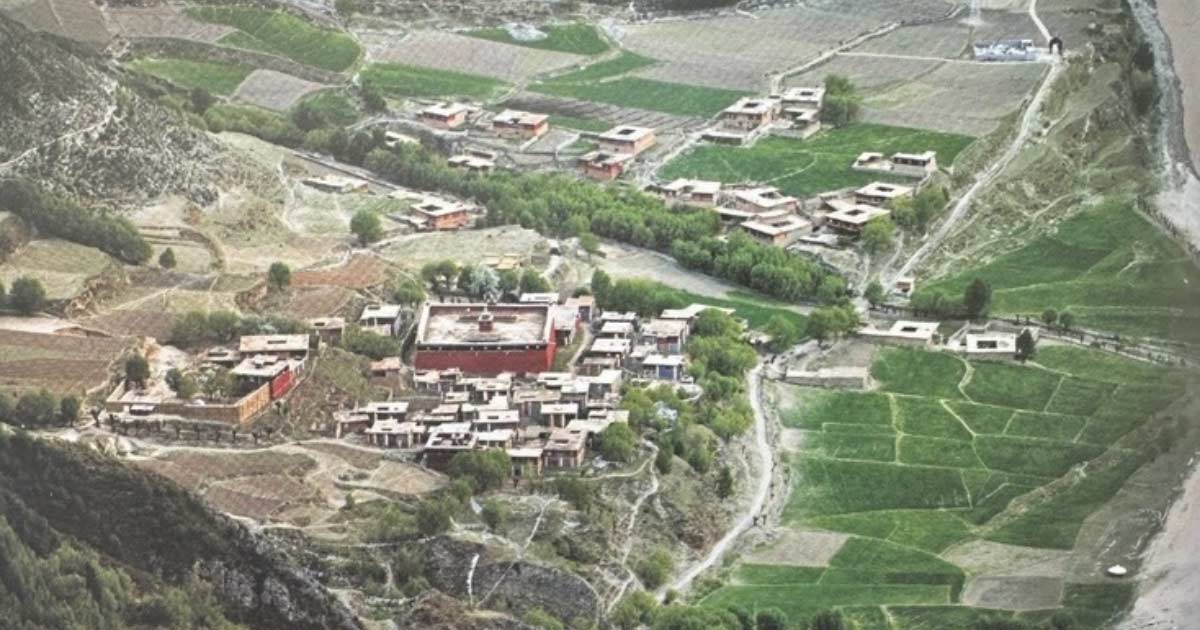

The film echoes to a certain extend the Kamtok dam on the Drichu River, a tributary of the Yangtze, in Sichuan province east of Tibet, which threatens to bury several villages as well as several monasteries including the historic monasteries of Wonto and Yena, which survived the Cultural Revolution and house important mural paintings dating for some of them from the 14th century.

Wontö Rabten Lhunpo Tse Monastery

14th century murals in Wontö Monastery offering a glimpse into the rich artistic traditions of Tibet.

Several hundred residents demonstrated in Dege County to implore the Chinese authorities to reconsider their decision. On February 22, armed police arrested numerous Tibetan monks from Wonto and Yena monasteries as well as local residents, many of whom were beaten and injured. Video footage shows Chinese officials in black uniforms forcibly restraining the monks, who can be heard shouting to stop the dam’s construction. The Chinese authorities’ response was very heavy-handed, with numerous arrests. Several local representatives remain imprisoned to this day, facing heavy prison sentences for their peaceful mobilization (see ICT report).

Alternatives to hydroelectric dams

Although there is a global consensus on the need to accelerate investment in renewable energy to reduce the effects of climate change, hydroelectric dams carry inherent, serious and disproportionate risks for the local environment and residents and in many cases contribute to climate change. It is important to assess each hydroelectric dam project on a case-by-case basis, whether in France on the Loire, in the USA, in Brazil or in Tibet, and to remain cautious about the range of risks and costs involved. There are other paths to renewable energy development, and all sustainable paths are based on the rule of law, transparency, inclusion and accountability.

As with the mega-basins in France, we call for a moratorium on all dams under construction or planned in Tibet.

A note of hope: the Indian tribes of the Klamath Basin

To end on a hopeful note, I’d like to highlight the victorious battle won by the indigenous Indian tribes of the Klamath Basin, a river in the western United States in California, against four hydroelectric dams that threatened their survival and that of the salmon are to be dismantled. They won their case and the state was forced to dismantle these infrastructures, an unprecedented undertaking to restore a river. This is the epilogue to a war that has been going on for over twenty years between ranchers, landowners, tourism professionals and the “salmon people”, the indigenous tribes whose fate has steadily declined along with that of the river. And, for once, the Indians have won.