Yudru Tsomu’s meticulously researched new book, Chieftains, Lamas, and Warriors: A History of Kham, 1904-1961, provides a welcome addition to narratives on Tibetan history by framing Tibet’s eastern province not as a remote periphery but instead as a crucial zone of contestation between Central Tibet and China.

In doing so, Tsomu shows a line of continuity between successive governments of China that otherwise have little in common: namely, how swiftly each one resorted to violence in their efforts to extend sovereignty over non-Chinese lands.

The more things change…

A History of Kham begins in 1904 during the waning years of the Manchu Qing empire. It then follows developments in Kham during the founding of the Republic of China, the Warlord Era, the Nationalist government, and finally through the rise of the Communist Party and the establishment of the People’s Republic of China.

Each of these regimes attempted to take control of Kham with varying degrees of effort and success. Over the span of a few decades the Khampas were subjected to incursions by murderous Manchu bannermen, despotic Sichuanese warlords, and the People’s Liberation Army, which relied on brutal violence to secure an occupation that continues to this day.

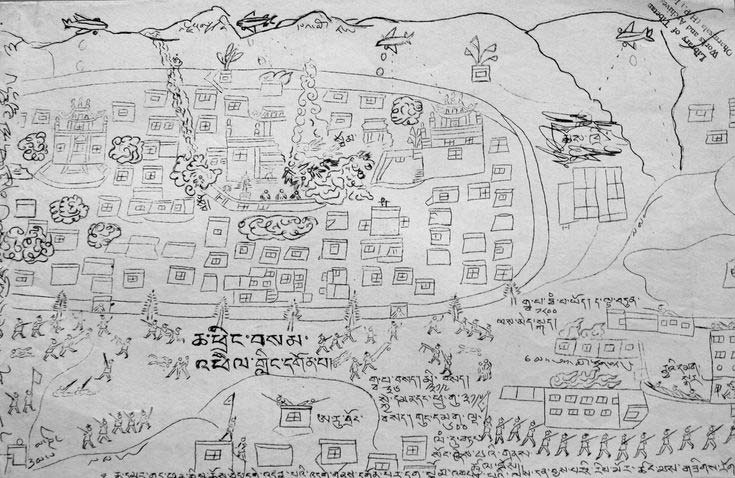

Despite the wildly differing ideologies of these governments, each one reached for the same set of tools upon encountering Tibetan resistance to their rule; the Qing general Zhao Erfeng (1845-1911) earned the title “Zhao the Butcher” for slaughtering Tibetan villagers and burned down monasteries in 1905, the warlords who succeeded the Qing dynasty used their armies to punish Tibetans for resisting, and in 1956 Mao’s China employed methods of destruction Zhao Erfeng could have scarcely imagined when they used Tupelov Tu-4 bombers to assault Lithang Monastery.

Illustration of the aerial bombardment of Chatreng Monastery, another major monastery in Kham.

Zhang Yintang, a Chinese official who served in the Qing and Republican eras, expressed this philosophy succinctly. “China should rule Tibet as Britain ruled India,” he said as he unveiled a campaign of forced assimilation which serves as a prequel to the CCP’s current effort.

… the more they stay the same

Consider some of the incidents detailed in A History of Kham.

- In 1904, the Qing Empire’s Sichuan Governor-General Xiliang ordered the provincial commander-in-chief to embark on a punitive expedition in Kham after the monks of Gartar Monastery and local Tibetans attempted to disrupt a Chinese mining operation that had been established in Tibet.

- In 1912, Tibetans in Drakyab revolted against Chinese rule, and a general serving Yuan Shikai’s Beiyang government brutally suppressed the revolt and burned down Yemdo Monastery.

- In 1920, Tibetans in Bathang rose up to expel Chinese commander Yang Dexi and his garrison. Their attempt to restore Tibetan leadership in Bathang failed, and Yang executed the leaders of the uprising.

- In 1932, Chinese warlord Liu Wenhui dispatched a regiment for a punitive expedition against Gara Lama in the town of Tawu, which had thrown off Liu’s control.

- In 1936, Red Army units on the Long March entered Kham. Tsomu notes that despite disciplinary measures, Communist troops still went on rampages.

- In 1937, Guomindang commander Zeng Yanshu violently suppressed a Tibetan rebellion in Gangkar Ling.

- In 1956, Tibetan revolts against Chinese rule occurred in 18 of the 21 counties of Kardze prefecture. The Chinese People’s Liberation Army used overwhelming force to quell the uprisings, including the aforementioned aerial bombardment of Lithang Monastery.

Over this period empires, warlords, republics, and people’s republics came and went, but Chinese forces securing control of parts of Kham through violence remained a constant.

The targeting of Tibetan monasteries continues to the present. The CCP justifies their ongoing efforts to restrict, control, and eliminate Tibetan Buddhism according to their own principles, but these assaults on monasteries are consistent with prior regimes which held completely opposite principles. Only the justifications change: “disobeying the emperor” for the Qing, “securing the border” for Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalists, and “smashing the reactionary upper class” for the Communists.

In reality they have always been, first and foremost, efforts to break down centers of Tibetan nationalist power in order to subjugate Tibetans to Chinese power instead. Modern Chinese propaganda on the subject is shaped by Beijing’s persistent efforts to frame Tibetan resistance as a class issue, but their true motivations clearly line up with those of previous Chinese governments trying to impose their rule on an unwilling Tibetan population.

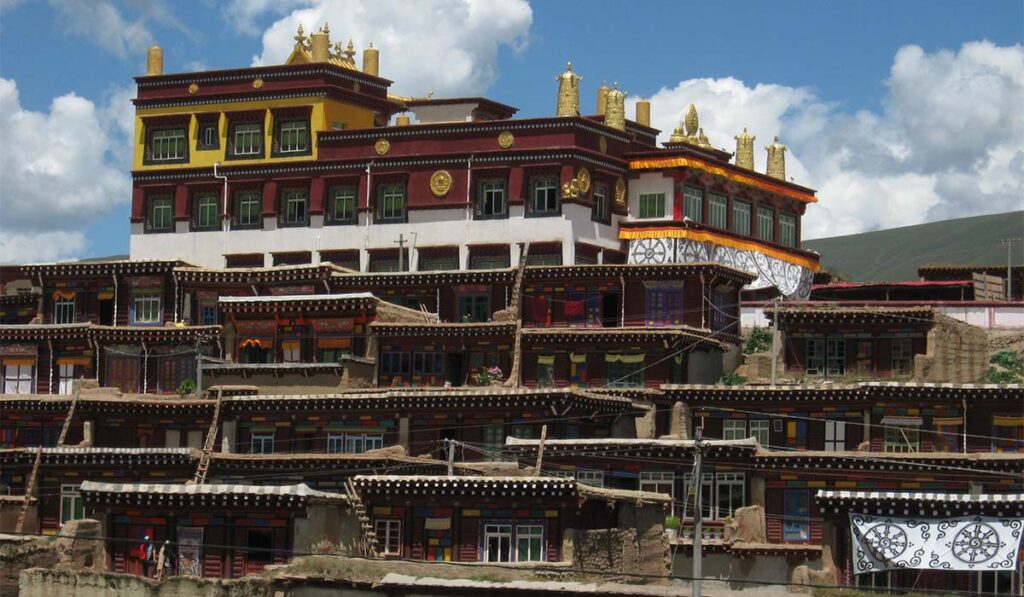

Dargye Monastery provides an instructive example of this continuity in action. A large institution located in Kham with close ties to the Tibetan government in Lhasa, it was assaulted by Chinese forces in a 1930 punitive campaign and then ransacked again and burned down in 1932. Under Communist rule – theoretically the antithesis to the Guomindang – the monks would be forced to leave the monastery in 1958, and it would be completely demolished during the Cultural Revolution before later being rebuilt.

Dargye Monastery today (Photo: Andelicek.andy)

Kham since 1961

Tsomu’s book ends in 1961, but the story doesn’t stop there.

Dargye Monastery, for example, remains a center of both Tibetan resistance and Chinese repression to this day. In 2008 a Dargye monk named Kunsang Tsering staged a peaceful protest and was shot by members of the People’s Armed Police, while in 2011 two Dargye monks were arrested for shouting slogans in Lhasa’s Barkhor district, including “We want freedom and human rights in Tibet.” Five years later, Chinese authorities cancelled a religious gathering and horse race festival organized by Dargye Monastery after monks and local residents refused an order to fly the Chinese flag at the two events, at the monastery, and from residents’ homes.

Efforts for forcibly converting Tibetans into Chinese culture have continued as well. As part of their linguistic repression of Tibetan, in recent years Chinese authorities have been busy forcibly closing Tibetan schools and replacing them with a system of colonial boarding schools.

Some of the figures mentioned in A History of Kham have received something of a recent reappraisal. The Chinese Communist Party would never endorse the Qing Empire’s methods of rule over China, but how about in Tibet? Tibetan writer Woeser noted that Zhao the Butcher, a certifiable homicidal maniac, has been given the seal of approval by from current Chinese leaders and nationalist voices:

Many Chinese mention that Zhao Erfeng killed Han Chinese people, which they consider the “dark spot in his life,” but his evil behavior in Tibet is endlessly being praised; one finds headlines such as “the misunderstood national hero of the last century,” “the historical contributions of the great Qing minister Zhao Erfeng who led an army into Tibet to put an end to the rebellions,” “cherish the memory of the national hero Zhao Erfeng,” or “recapturing a Tibetan hero.” This very clearly shows that killing Han Chinese is cruel and mean, whereas killing Tibetans is an act of patriotism.

Ruling Tibet like the British ruled India, indeed.