There are multiple ways to view China’s decade-long refusal to return to the negotiating table with the Tibetans. For example, it can be seen as proof of China’s intent to resolve the Tibet issue through repression and forced assimilation instead of dialogue and compromise, as the result of Xi Jinping’s authoritarian outlook, or, within the Tibet movement, as a point of contention between different strategic approaches.

For the American government, this 12-year period without further dialogue should be seen as a failure to achieve one of America’s foreign policy goals. The Tibetan Policy Act of 2002 establishes that it is American policy to promote dialogue without preconditions between Tibetans and the Chinese government and to “explore activities to improve prospects for dialogue, that leads to a negotiated agreement on Tibet.”

The fact that negotiations have not been concluded, and in fact that they have not taken place since 2010, should, therefore, cue an effort to see what more can be done. The American government has consistently taken some opportunities to press China to resume dialogue; see the most recent Report to Congress on Tibet Negotiations for examples. But it is becoming very clear that the current efforts aren’t sufficient to revive the dialogue process. What the United States is doing now isn’t succeeding in bringing China back to the negotiating table, making it incumbent on the government to reevaluate its efforts and find new ways to pursue this policy goal.

The Congressional-Executive Commission on China’s latest hearing on Tibet examined the barriers to dialogue. ICT’s report on the hearing lays out some of the biggest takeaways, and it can be watched in its entirety here. In brief, the commission heard from Professor Hon-Shiang Lau on the falsehood of China’s historical claim to Tibet, from Tenzin N. Tethong on the Sino-Tibetan dialogue process, from Professor Michael van Walt van Praag on how China’s occupation of Tibet violates international law and from writer/activist (and ICT Board of Directors Member) Ellen Bork on the development of America’s Tibet policy.

Tenzin N. Tethong, Hon-Shiang Lau and Michael van Walt van Praag at the CECC hearing. Eagle-eyed readers might recognize staff members of the International Campaign for Tibet among those seated behind them.

Where the United States can go from here

Considering the facts raised at the hearing, I believe several steps are needed to bring the government’s actions in line with its policy goal of successfully concluding the dialogue process.

First, the United States should do no harm. For years China has been using American statements referring to Tibet as a part of China to undermine America’s policy goals for Tibet; Beijing insists that calling Tibet a part of China—even in a statement urging China to resume negotiations—commits a country to abandoning the Tibetan side. In 2014, for example, Chinese Foreign Ministry Spokesman Qin Gang criticized President Obama for meeting with the Dalai Lama, accusing him of reneging on American’s “commitment of recognizing Tibet to be a part of China.”

The best way to undercut this tactic is to stop referring to Tibet as a part of China. As Professor Lau points out, it isn’t true historically, and as Michael van Walt points out, it isn’t true according to international law. Each time the United States says it, then, it is strengthening China’s hand and weakening Tibet’s case. It’s worth noting that the State Department removed a sentence which called Tibet a part of China from the 2020 Human Rights Report, as Sens. Leahy and Rubio approvingly noted at the time, although it was disappointing to see it reappear in the 2021 Report to Congress on Tibet Negotiations. Congress, meanwhile, has passed legislative language intended to prevent the State Department from recognizing Tibet as a part of China in the absence of a negotiated agreement between China and the Tibetans.

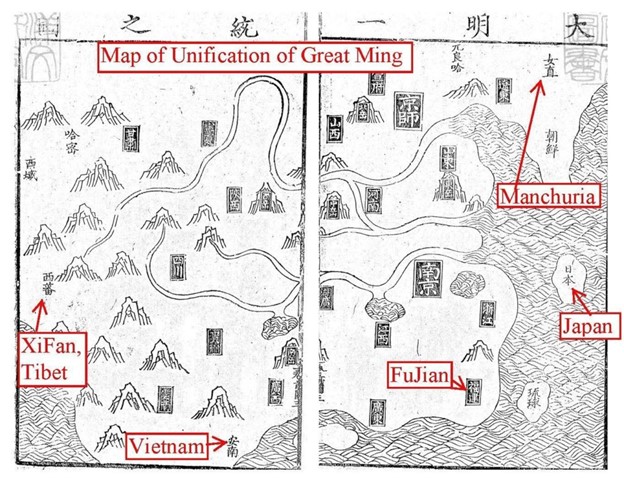

A Ming Dynasty map of China procured by Hon-Shiang Lau shows Chinese territories with shaded backgrounds, while foreign countries such as Japan, Vietnam, and Tibet are shown with white backgrounds.

Second, the United States should draw a clear line on Tibet and the Central Tibetan Administration. Before the Chinese invasion, Tibet was referred to as a country separate from China on multiple occasions by the United States government, and in the years after the invasion, the US continued to do so. Acting Secretary of State James Webb wrote in 1951 that the United States did not consider Tibet a part of China “except to the extent that it is occupied by Chinese Communist forces,” and Congress referred to Tibet as occupied in the Foreign Relations Authorization Act for Fiscal Years 1992 and 1993.

Beijing has not done anything since then to establish legitimacy for its rule in Tibet, and beyond merely declining to refer to Tibet as a part of China, the United States should not shy away from pointing this out. When the PRC claims that Tibet has been a part of China since ancient times, or refers to Tibet as an internal issue, the United States should be ready to refute both ideas and state unequivocally that Tibet’s future status remains an unresolved question that can only be settled through negotiations with the Tibetan side—which is to say, the Dalai Lama and the leaders of the democratically elected Central Tibetan Administration, who are legitimate representatives of the Tibetan people.

US Special Coordinator for Tibetan Issues Uzra Zeya meets with the Dalai Lama in Dharamsala, India, home to the Central Tibetan Administration.

Finally, if the current level of pressure on China isn’t sufficient, the United States must adjust accordingly and find ways to increase this pressure. Beijing wants Washington to stop mentioning Tibet or, failing that, to do so either behind closed doors, perfunctorily, or both. Based on the most recent Tibet Negotiations Report it seems that neither President Biden nor Secretary of State Blinken pushed for a resumption of dialogue in private conversations with Chinese leaders; they certainly haven’t done so in public forums with the PRC. This clearly isn’t helping to promote America’s policy goal with Tibet.

Senior government figures should treat China’s refusal to conclude negotiations with the Tibetans like a problem they need to actively solve, not a foregone conclusion or a box to check off in statements. Beijing’s continued absence at the table is not a justification to put America’s policy goals for Tibet aside; it is, in fact, the very reason that the US adopted them in the first place. Reviving dialogue is a challenge that the White House, State Department and Congress must rise to meet.

Breaking down the barriers

As a candidate, Joe Biden promised that “a Biden-Harris administration will stand up for the people of Tibet.” He went on to specifically pledge that his administration would “work with our allies in pressing Beijing to return to direct dialogue with the representatives of the Tibetan people to achieve meaningful autonomy, respect for human rights, and the preservation of Tibet’s environment as well as its unique cultural, linguistic and religious traditions … and step up support for the Tibetan people.”

This promise is rooted in longstanding American policy, and now it is time to translate this policy and this promise into heightened pressure and stronger requests, incentives and engagement with Beijing on Tibet. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi and Rep. Jim McGovern recently promised new legislation designed to “encourage a peaceful resolution to the ultimate status of Tibet,” and the White House must interpret this legislation as a mandate for bolder action to end the occupation of the Land of Snows.