On Dec. 21, just four days before its rescheduled session was to begin, the

Tibetan Parliament-in Exile announced that it was being postponed again to March, this time due to lack of a quorum.

The initial postponement was made on Sept. 28, 2023, when the Tibetan parliamentary secretariat issued a terse notice saying, “The remaining business of the 6th session of the 17th Tibetan Parliament-in-Exile has been postponed due to the absence of the requisite quorum needed for the session to constitute.” This brought an uncertain close to the latest development in Tibetan diaspora politics that left some observers wondering whether Tibetan democracy in exile was failing?

On Nov. 16, 2023, the parliament made an announcement that it “will reconvene with the remaining business of the general session from 25th to 29th December 2023.” And thereby hangs a tale.

I had then wanted to write about this development looking at the overall state of Tibetan democracy, as the parliament is merely a part of it. As I began to draft something, another development took place in Washington, DC, in the US House of Representatives, on Oct. 3, 2023, leading to the dismissal of then-Speaker Kevin McCarthy and the inability of the House Republicans to come up with a viable new candidate, which paralyzed the House session. It was only on Oct. 25 that Republicans were able to somehow come up with a choice of a speaker in Representative Mike Johnson. Even now there is only temporary peace in the House, so to say.

The development in Washington, DC made me look at what happened in Dharamsala in relation to the fate of democratic institutions in the world in general. It would not be inaccurate to maintain that democracy can become as strong or as weak as its participants want or permit it to be, whether in one of the oldest democracies like the US, the largest democracy in India or the borderless democracy of the Tibetans in exile.

Exiles have democracy while those in Tibet suffer authoritarianism

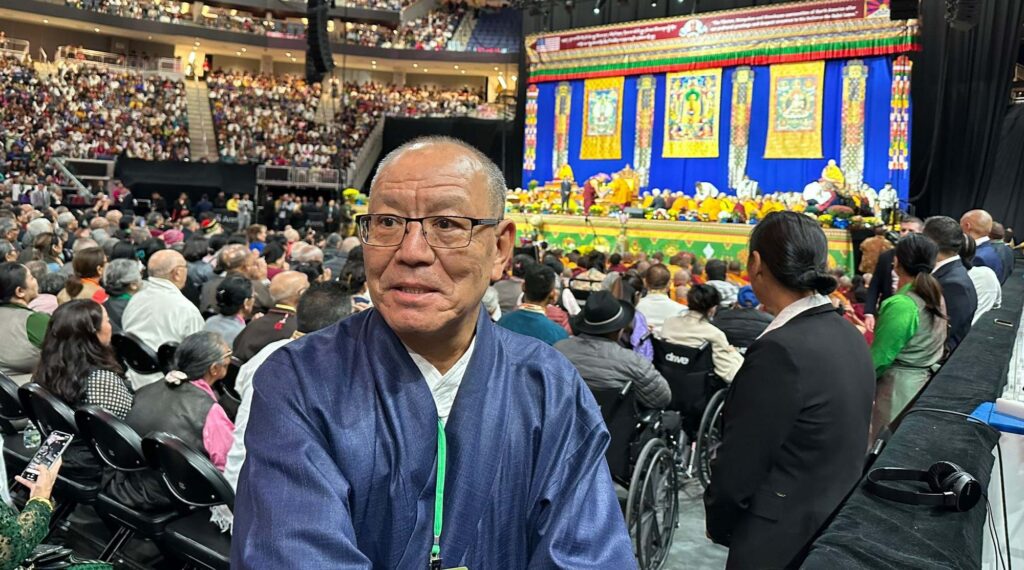

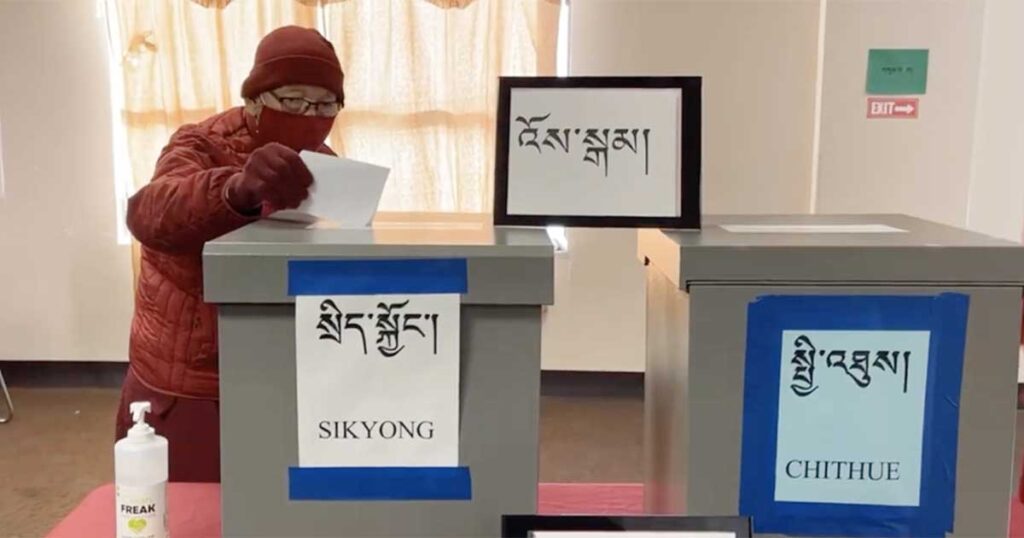

Let us put Tibetan democracy in perspective first. In stark contrast to the Tibetans in Tibet who live under an authoritarian regime and are denied their fundamental human rights, leave aside political franchise, the small population of Tibetans in Diaspora has been undergoing a unique experiment in democratic governance at the insistence of H.H. the Dalai Lama. This has been taking place both in the temporary headquarters of Dharamsala in India, as well as in all Tibetan communities in the Indian subcontinent and abroad, adapted to meet the needs of the local situation. Since 2000, the Tibetan leadership at the central level has been shaped by the direct will of the voting populace and been represented by the elected political leader (now known as Sikyong) and the parliamentarians. In short, despite the limitations posed by their situation, Tibetans in exile are better off than our brethren in Tibet.

However, democracy is a double-edged sword. When those participating in it exercise their franchise responsibly, there is progress. But when some participants do not do so, they can lead to the stagnation or, worse, the retrogression of the society. The irony will be that people who fall in either of these categories will stick by their position, asserting that they are exercising their democratic rights.

Secondly, democracy does not operate in a vacuum but has to function within the framework of a given society. It is again up to the participants whether or not they take into consideration the prevailing factors in undertaking their actions. Their decisions have consequences.

Dalai Lama’s intervention resolves a problem

This was most recently apparent since the beginning of the current parliament in 2021. The parliamentarians’ term began in an unusual manner on account of disagreement on the nature of taking their oaths of office. This was because some of them declined to take their oath before the then-speaker pro tempore on account of another development during the previous parliament, which is beyond the scope of this blog post. This led to a four-month impasse and a political vacuum, including the newly elected Sikyong not having any ministerial colleagues in the absence of a parliament to confirm them. In any case, this latest development has added fuel to the ongoing discussions about the perceived degeneration of the Tibetan society in diaspora, leading people to wonder about the future of the precious democracy that we were provided by the Dalai Lama. Even the US government had somehow felt it necessary to intervene, indicating the sense of concern even beyond the Tibetan community. In an unprecedented development, even the US State Department made a public call to the Tibetan parliament to resolve its issues. In a letter in August 2021, the State Department said, “Disputes over parliamentary procedures which are not resolved in a timely manner and in accordance with the rule of law risk undermining the confidence placed by the Tibetan diaspora and the international community in the CTA and TPiE. We urge the elected members to move past their differences and turn to the pressing matters that need their attention.”

Ultimately, unable to reach a solution themselves, the newly elected parliamentarians supplicated to His Holiness the Dalai Lama, and his intervention led to the parliament members taking their oath of office in October 2021 and being able to begin their work.

Speaker Pro Tempore Dawa Tsering addressing the Parliament after the members resolved their issue of the mode of taking their oath in October 2021. (Photo: https://tibetanparliament.org)

While the developments relating to the Tibetan parliament are certainly concerning and are negatively impacting the democratic process, at the same time they need to be looked at from the broader perspective.

Evolution of democratic governance in exile

Acknowledging the drawbacks of the administrative system in Tibet, the Dalai Lama implemented a series of initiatives to empower the Tibetan people soon after coming into exile. In 1960, His Holiness introduced the concept of representative democracy by asking Tibetans to elect their deputies to a “Commission” (now formally known as the Tibetan Parliament-in-Exile) that would have a say in the governance of the Tibetans in exile and also be a preparation for a future democratic Tibet. He then followed it up a few years later with the promulgation of a draft constitution for future Tibet, thus introducing the concept of rule of law of this nature. Much to the consternation of the Tibetan public he mandated that this constitution retain an impeachment clause to be applied to the Dalai Lama, if the need arises. This was a very important message that the Dalai Lama was sending, namely that the institution should be more important than individuals and that no one should be considered above the law.

His Holiness also laid out the infrastructural basis in the form of the Central Tibetan Administration and the various organs under it to implement democratic governance.

Initially, the parliamentarians were virtually embedded in the different offices of the CTA to be part of the direct governance.

In subsequent years, the Dalai Lama took further steps in empowering the Tibetan people; from enfranchising the people to elect the ministers (who were until then appointed by him); to the drafting of a Charter, specifically to govern the Tibetan Diaspora, which included provision for the establishment of the three pillars of democracy, legislative, executive, and the judiciary. The authority of the Tibetan parliament was clarified to separate it from the executive and expanded to highlight its legislative functions becoming the highest policymaking body in the Tibetan administration. In the case of the judiciary, given that the Tibetan Diaspora operates under host countries, the process was adapted to the prevailing situation. Thus the judiciary that was introduced to the Tibetan community is the Tibetan Justice Commission that works under the alternative dispute resolution system as permitted under arbitration laws of any country.

The Dalai Lama’s devolution of his political authority

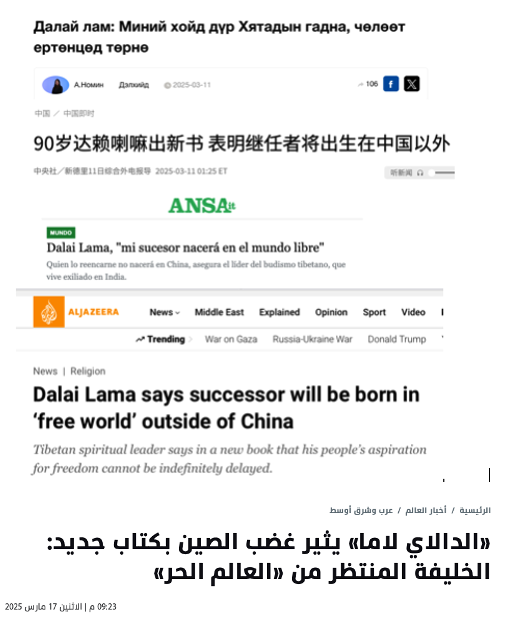

The Tibetan people were able to embrace these changes, some unwillingly though, as they had remained assured of the Dalai Lama’s role as the “head of state and government.” But a significant change took place in 2011 when the present Dalai Lama not only gave up all his political authority in favor of an elected Tibetan leadership, but also virtually removed the institution of the Dalai Lamas from all future political roles.

When His Holiness had initially broached the idea of his devolution of authority, there were concerns among a section of the Tibetan people about whether we were ready to shoulder the needed responsibility ourselves. His Holiness had then said it was better that the people tread on this path of self-reliance while he was still active as he could then provide guidance if things went astray.

In his announcement of this devolution of authority on March 19, 2011, His Holiness outlined the role of the Dalai Lama institution and the support and reverence he himself was receiving from the people. He continued, “If such a Dalai Lama with an unanimous mandate to lead spiritual affairs abdicates the political authority, it will help sustain our exile administration and make it more progressive and robust.” His Holiness also expressed his optimism: “So, the many political changes that I have made are based on sound reasons and of immediate and ultimate benefit for all of us. In fact, these changes will make our administration more stable and excel its development. So, there is no reason to get disheartened.”

Democratic institutions at the grassroots level

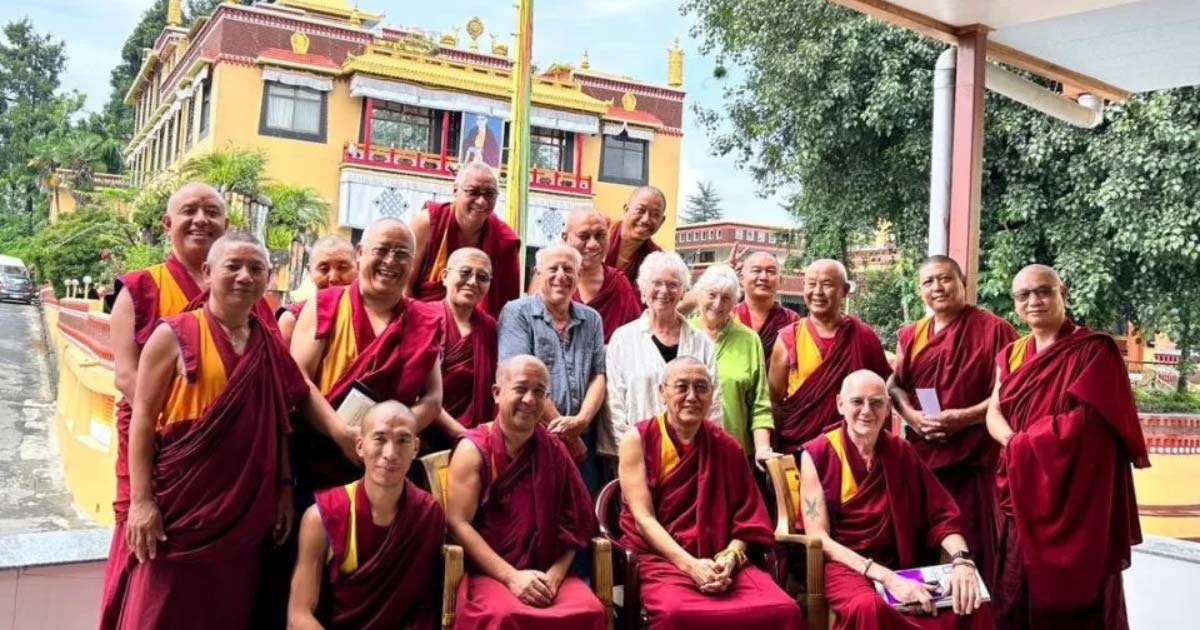

Tibetan democracy should not be seen in the context of the institutions in place in Dharamsala alone. Even while working to resettle the Tibetan refugees in the different settlements in the Indian subcontinent, His Holiness had the foresight to introduce grassroots democracy. I have not done a survey of the situation in all the settlements, but in the first settlement that began in Karnataka, Lugsung Samdubling in Bylakuppe, this empowerment began at the “camp” level, comparable to a village. The Lugsung Samdubling settlement had six such camps composed of 100 houses. Householders (Pachens as they were called) in every 10 houses elected their Chupon (leader of 10) to represent them while the camp as a whole elected two Gyapons (leader of 100) as camp leaders to look after the overall camp affairs. Such camp leaders were also known as Chimi (public person). Given that agriculture was the primary means of earning a livelihood the settlement also had a co-operative society (established to support their economic life) whose affairs were run by a board of directors elected by residents of each of the camps. In the early days when the cooperative society ran all-purpose stores in each of the camps, even the storekeepers were elected by the respective camp residents.

It was the camp leaders, assisted by the Chupons, who looked after the welfare of the residents. They would oversee water supply, undertake spiritual, cultural and social activities for the camp as a whole, be the coordinator between the co-operative society and the residents on agricultural work (including arranging for ploughing schedule and selling of crops). They would also be the mediators for any disputes between residents or even within a family. Since the local post office did not deliver mail to individual houses but deposited all mail with the camp leaders, they also had to serve as delivery persons of the mail. The camp leaders met with the Chupons to discuss issues, and for major matters they would convene a householders’ assembly for decisions.

Growing up in the Lugsung Samdubling settlement, I would see the camp residents eagerly taking part in elections for their Chupons, Gyapons and Board of Directors to the co-operative society. As quite many of the people were illiterate then, symbols like those in the eight auspicious symbols were assigned to candidates, and these would be pasted on the ballot boxes so that people could decide whom to cast their votes for.

Almost all the settlements would have elected camp leaders or other similar positions. This grassroots system of democracy in the settlements continues to this day with a new generation of younger residents taking over the mantle of the camp leaders and other locally elected positions.

Also, at the settlement level, there are co-operative societies that have been set up to assist the settlers in their socio-economic life. Their board of directors are elected by the people in the settlement who also technically own shares in the societies. Following democratization, these societies, which used to be administered by Dharamsala, are now overseen by a Federation of Tibetan Cooperatives (FTCI). FTCI lists 10 such societies under it in different Tibetan communities in India.

Signboard of a store for the Kunpheling Tibetan settlement in Sikkim, northeast India, run by its cooperative society (Photo: www.nyamdel.com)

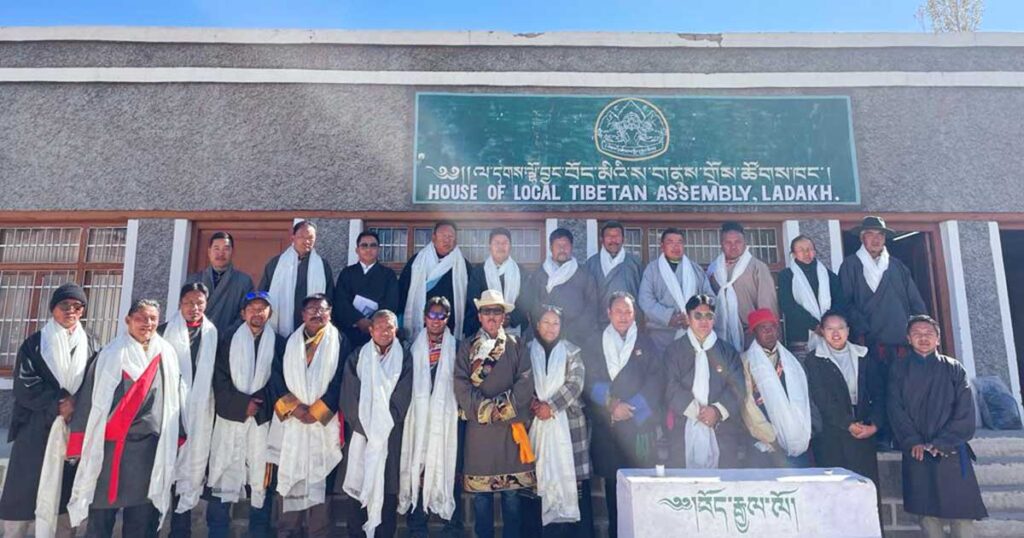

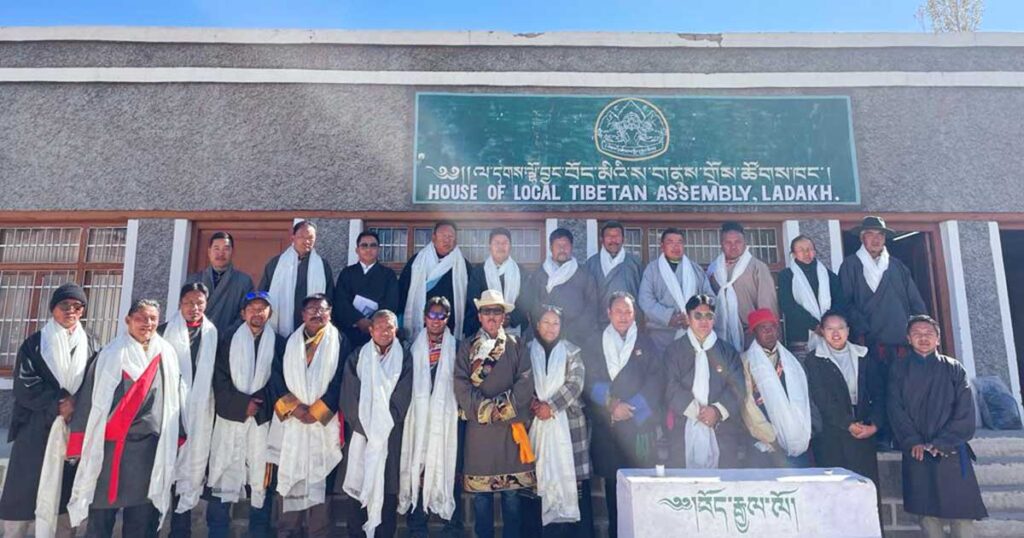

Since the promulgation of the Charter of Tibetans-in-Exile, there is provision for Local Tibetan Assemblies, to be composed of deputies elected by the people in the area to be the watchdog of the work of the settlement office in the region. The Tibetan Parliament website currently lists 40 such local assemblies in the Indian subcontinent as well as in Switzerland.

11th Local Tibetan Assembly of the Tibetan settlement in Leh, Ladakh after their swearing in on Oct. 30, 2023. (Photo: www.tibet.net)

Is the Parliament impeding Tibetan democracy?

The parliament is seen as the symbol of Tibetan democracy, as is the case with other democracies. Therefore, when parliamentarians, individually or collectively, become embroiled in controversies, there is an immediate negative impact in the public’s eye. This is the situation that Tibetans are in currently. Our parliamentarians who swear by democracy somehow end up being seen as causing impediments to the governance system. The disappointment is more so with the younger parliamentarians upon whom much faith was placed that they would be different from their “green-brained” (a derogative term for older people who are perceived as not using their brains) older colleagues. If not their action, the rhetoric of some of them does give that impression that they, too, subscribe to the herd mentality. Observing the proceedings of the parliament one cannot but avoid reaching the conclusion that consideration of personalities dominates discussions on substance.

The situation is further complicated by the surge in social media usage in the Tibetan community. To be fair, the rise of social media has had a positive impact in the community in many ways. It is common knowledge how social media, particularly messaging apps (unlike in the West students in India did not have individual access to computers and so had to depend on their mobile phones for their classes), were the lifeline for teachers to impart education to Tibetan children in India during the coronavirus pandemic when physical presence in classes was not possible.

Similarly, a major factor for the widespread craze for the Gorshey (circle dance) on Lhakar (White Wednesday) in the Tibetan community is because of social media that became the vehicle for Tibetans all over the world to impact each other. It did not matter whether they were residing in the remote settlement of Choephelling in Miao in Arunachal Pradesh, Bylakuppe in Karnataka, Gangtok in Sikkim (all in India), Pokhara in Nepal, Toronto in Canada or in Bhutan or any other places where Tibetans reside. This has also resulted in younger Tibetans taking pride in projecting their Tibetanness, whether in wearing Tibetan garments or speaking the language.

Tibetans in the remote settlement of Choephelling in Arunachal Pradesh in India, close to the Tibetan border, at one of the Gorshey performances. (Screengrab from a YouTuber: Evergreen ChungChung)

However, there have been negative impacts with the advent of social media, as individual content creators do not need to take into consideration accountability. Thus, issues are amplified and distorted and every development is followed by a blame game with polemical utterances through factional taking of sides.

We should, however, remind ourselves of the initial two-pronged objectives His Holiness the Dalai Lama had after coming into exile: to look after the socio-economic welfare of the Tibetan community and to resolve the Tibetan political problem. Thus, it is a no-brainer to realize that all of us should utilize our democracy to work to solve the Tibetan problem rather than lead to the community’s weakening. This power of democracy that the Tibetans have attained in the post-1959 period has enabled united efforts under His Holiness the Dalai Lama, which have been a source of hope for the Tibetans in Tibet and of concern for the Chinese leadership. Not only do the Chinese officials have concerns, but ironically there is an expectation from the Chinese leadership side that the CTA is capable of much more than what it is doing. As a case in point, way back in 1993, during a secret meeting to discuss their public relations strategy on Tibet, one of the Chinese government officials said, “According to analysis, since the beginning of 80s, the splittist activities of the Dalai Clique [the demeaning Chinese term to refer to the Tibetans in exile under the leadership of His Holiness the Dalai Lama] have entered a new cycle. It is still in the process of developing and has (not) yet reached its peak stage.” Thus, the Chinese government is certainly cognizant of the potential of the Central Tibetan Administration. There is the opportunity for all of us to prove to the Chinese authorities that they were right, at least on their expectations about the Tibetan leadership in exile.

In one sense, it is good that problems, like the recent one with the Tibetan parliament, are taking place now while corrective measures can be taken and when we have the presence of His Holiness the Dalai Lama to provide guidance, if all other efforts fail. But we need to think deeply.

The Tibetan people need to change their mindset on their understanding of democracy. Currently, whether it is the parliament or the public, it appears that we are only copying the worst of democratic practices of East and West. Unlike those countries, we Tibetans do not have the luxury of focusing on side issues and neglecting the more fundamental aspect. To the Tibetans in exile, democracy is not the end, but the means to get to the political end, and our recognizing that can pave the way for a smoother running of the Tibetan governance system.

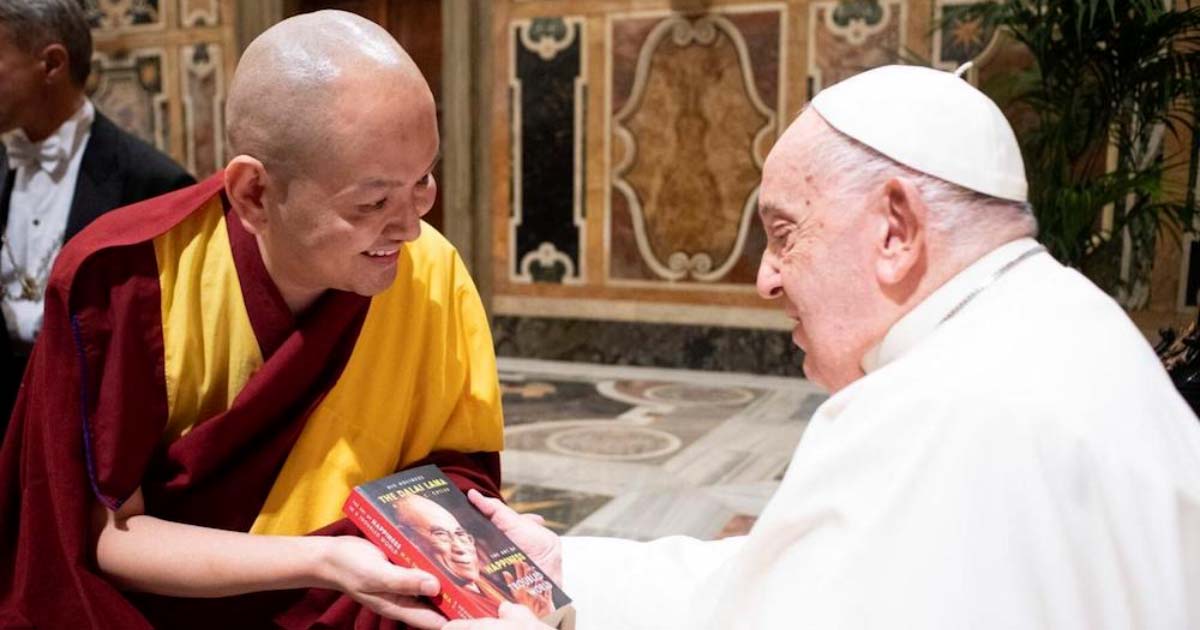

The third initiative was in the form of a book, Our Wish-fulling Gem Part 2: A Biography of His Holiness the Dalai Lama” (Library of Tibetan Works & Archives, Dharamsala, 2025), by educationist Chophel compiling the details on visits by His Holiness the Dalai Lama throughout the world outside of India from 2011 till 2018. Additionally, this second volume also has details on His Holiness’ visits within India from 2011 onwards. As in the first volume, in this book, too, the author provides an overview of His Holiness’ meetings and remarks at events big and small in different countries which are “a testament to the enduring influence of one of the world’s most revered spiritual figures.” His first volume, titled “Our Wish-Fulling Gem: A Biography of His Holiness the Dalai Lama” was published in 2022 and covered the first 75 years of His Holiness’ life. The author and I know each other, and I had the opportunity to read a drafts of both books.

The third initiative was in the form of a book, Our Wish-fulling Gem Part 2: A Biography of His Holiness the Dalai Lama” (Library of Tibetan Works & Archives, Dharamsala, 2025), by educationist Chophel compiling the details on visits by His Holiness the Dalai Lama throughout the world outside of India from 2011 till 2018. Additionally, this second volume also has details on His Holiness’ visits within India from 2011 onwards. As in the first volume, in this book, too, the author provides an overview of His Holiness’ meetings and remarks at events big and small in different countries which are “a testament to the enduring influence of one of the world’s most revered spiritual figures.” His first volume, titled “Our Wish-Fulling Gem: A Biography of His Holiness the Dalai Lama” was published in 2022 and covered the first 75 years of His Holiness’ life. The author and I know each other, and I had the opportunity to read a drafts of both books.