The spread of an edited video clip depicting an interaction between the Dalai Lama and a young Indian boy on stage at a recent teaching has provoked intense discussions of cultural differences, children’s rights, and the line between appropriate and inappropriate behavior. The tenor of the coverage of this clip and the discourse surrounding it has, in turn, been deeply distressing to many Tibetans and Tibet supporters, and activists such as Lhadon Tethong, Jigme Ugen, Dhardon Sharling, Tenzin Pema and Tenzin Tsundue have shared their eloquent thoughts on the issue.

I can’t help but notice that some commenters are using the clip as a pretext to advance unrelated attacks on Tibet, the Dalai Lama and the Tibet movement, though. My colleague Ashwin Verghese covered some aspects of this phenomenon in his recent blog post, but given the way the discussion of the video clip has developed this week I want to take a closer look at one commenter: Boots Riley, the musician and filmmaker. In doing so, I want to examine three of the misleading or false claims he’s advancing and explore where they come from and why they appeal to some people.

In the interest of full disclosure, I have to admit that I didn’t pick Riley solely because of his relatively large reach. I’ve been a fan of Riley since 2009 when I heard Street Sweeper Social Club, his collaboration with Tom Morello. From there I found The Coup, his other band; their single “The Guillotine” has been a constant refrain for me in light of the political developments in the United States over the last few years. Riley’s film “Sorry to Bother You” was also a subject of some discussion in our office after it came out in 2018.

My intention is therefore not to criticize Riley personally but rather to look at how someone with genuine and heartfelt anti-imperialist and anti-racist sentiment can end up so firmly on the wrong side of this issue.

Distorted history

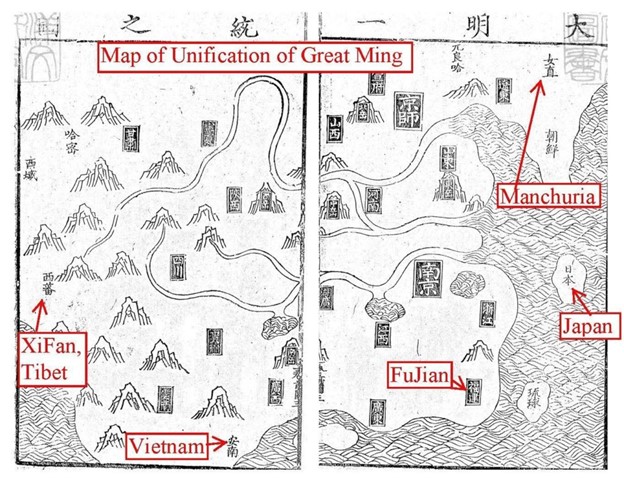

First, Riley has repeatedly advanced false claims about the social status of Tibetans before the Chinese invasion. It’s hard enough to come up with one word that covers the entirety of the very different systems that existed in different parts of Tibet; the lives of farmers in Tsang and nomadic pastoralists in Chabcha and town-dwellers in Dartsedo took place in vastly different political and social contexts.

As Riley tells it, though, pretty much all Tibetans were serfs. The issue of serfdom has been very thoroughly investigated and researched, and one of Robert Barnett’s chapters in “Authenticating Tibet” summarizes the results of this research:

Franz Michael and Beatrice Miller argued that the less loaded words ‘commoner’ or ‘subject’ are more accurate than the word ‘serf,’ [while] Dieter Schuh (1988) [shows] that in many cases they were not ‘bound to the land’ and so were not technically ‘serfs.’ W.M. Coleman (1998) has pointed out that in practice the Tibetans had more autonomy than appears in the written documents, and that Tibetans could equally well be described as peasants … Other scholars have noted that such social categories, Marxist or otherwise, are in any case rooted in European history and do not match the social system of pre-1951 Tibet, let alone the very different arrangements found among the people of eastern Tibet.

This may seem like splitting hairs; neither subjects nor serfs have the rights they deserve. But when you push a cartoonish claim that all Tibetans were serfs, meaningful criticism of the actual social hierarchy and human rights in Tibet becomes impossible. The real failings of the socioeconomic systems in Tibet—failings which have been critiqued by Tibetans themselves—fall to the wayside as peasants and nomads are transformed into serfs and then, in the most outlandish form, slaves. Who benefits from distorting the historical record in Tibet? It’s not Tibetans, nor is it Riley.

Second, Riley misstates China’s impetus for invading Tibet. In a tweet he claims that China had been pushing Tibet to reform its society prior to the invasion, but in fact Beijing’s rhetorical preoccupation with serfdom began only after the invasion was complete, and after their original justification—freeing Tibet from foreign imperialism—turned out to be untenable given the lack of major Western involvement in Tibet at the time.

There are keen ironies at play here. Ostensibly anti-imperialist Beijing was trying out and discarding various justifications for annexing another country, a classic imperial maneuver Americans will readily recall from the way the George W. Bush administration pivoted from weapons of mass destruction to ‘spreading democracy’ as a justification for the war in Iraq after finding that Saddam Hussein had, contrary to their claims, discarded his weapons of mass destruction programs. For their part, the only way Chinese occupiers could find armies of foreign imperialists in Tibet was by looking in a mirror.

Social reform as the impetus for invasion is also a poor fit for China’s actions after the invasion was complete. Instead of removing the Dalai Lama and addressing the conditions of Tibetan workers, Beijing gave the Dalai Lama and other senior clerical and aristocratic figures important positions in the new bureaucracy they established—a strange promotion to give someone they now claim was so greatly abusive.

In fact, it seems to be that the only major constituency Beijing was able to develop in Tibet during their first decade in power was among the top echelon of society itself, where some nobles and senior monks were swayed by China’s promises of preserving the status quo and a constant flow of silver. This, in turn, provoked derision and anger from common Tibetans who saw them as collaborators with an occupying force. Khenchung Sonam Gyaltsen, a monk official and to my knowledge the first official beaten to death by the Tibetan masses during the era of Chinese rule, was targeted not because of any social abuses but rather because of his cooperation with Chinese authorities.

Researchers like Benno Weiner and the Chinese writer Liu Xiaoyuan have documented how Beijing quickly alienated Tibetans, with policies formulated by Chinese leaders who had no understanding of Tibet’s culture and society – and little interest in learning. Who benefits from trying to recontextualize an imperial annexation into a war of liberation? Again, it’s not Tibetans, nor is it Riley.

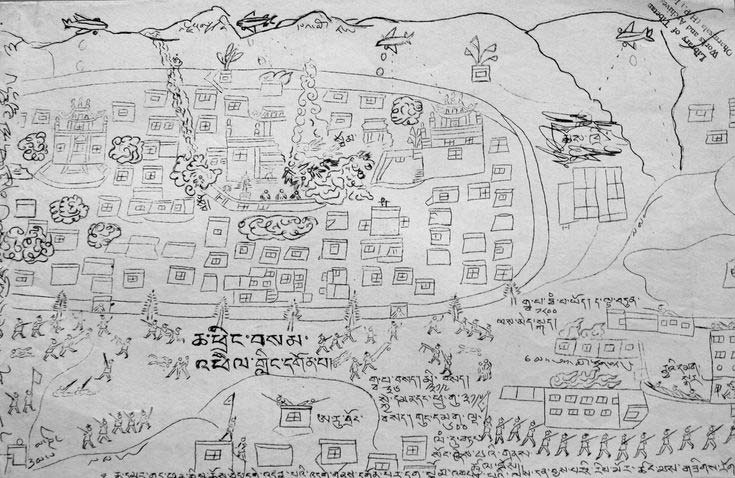

Third, Riley misleadingly portrays Tibetan armed resistance as the result of CIA covert action. It’s well-known that the CIA provided arms and training to some Tibetan guerillas, but Riley’s claim elides the fact that grassroots Tibetan uprisings against Chinese rule in Tibet and the development of a unified resistance movement predated CIA involvement, which was fairly limited in scope. To attribute Tibetan armed resistance primarily to the CIA only serves to fundamentally misrepresent the nature of this resistance. Beijing would have you believe that lamas and aristocrats and CIA agents forced common Tibetans to take up arms, but there’s plenty of evidence that on the contrary many common Tibetans were in fact deeply frustrated that much of the ruling class seemed paralyzed by – or perhaps even permissive of – China’s invasion.

Tibetan guerillas display captured Chinese weaponry.

By late 1955 Tibetans in eastern Tibet had begun planning, without any support from the Tibetan government in Lhasa or any foreign power, to rise up against Beijing’s increasingly abusive rule. By 1956 fighting was widespread across Kham, and in 1958 local uprisings in northern Tibet—again, fueled by popular resistance to Chinese rule and without any assistance from outside parties—were put down with extreme bloodshed by Chinese authorities. The formation of Chushi Gangdruk, the unified resistance army, took place in summer 1958.

In contrast to the underground organizations and mass uprisings led by the Tibetans themselves, the CIA involvement began by training a half dozen guerillas in how to use radios, small arms and guerilla tactics. Although the numbers grew later and America continued to supply them with arms for some time to come, the great popular uprisings against Chinese rule in 1956, 1958 and 1959 were all started and sustained by Tibetans, mostly or entirely with weapons they had purchased themselves or stolen from Tibetan military bases.

If Riley were to ask Tibetans, he would find that there are a wide range of opinions about the CIA’s involvement, and plenty of them are guided by anti-imperialism. Some people are grateful for the supplies, which were put to use including during the Dalai Lama’s flight to India, but many other Tibetans are frustrated that the CIA gave the Tibetans just enough to irritate China but not enough to expel it, spending Tibetan lives in the process. In the words of Gyalo Thondup, one of the chief Tibetan interlocutors with the CIA:

For the twenty-five thousand resistance fighters on the ground in Lhokha, the CIA supplied about seven hundred guns. For the five thousand fighters active in Amdo, the CIA dropped maybe five or six hundred rifles. An area with two thousand fighters got maybe three hundred or four hundred … Had I understood how paltry the CIA’s support would be, I would never have sent those young men for training. Mao was not the only one to cheat the Tibetans. The CIA did, too.

If Riley wants to critique the CIA’s involvement in Tibet, there’s his angle – and straight from the mouth of a Tibetan. But accepting Gyalo Thondup’s perspective would require acknowledging widespread popular opposition to Chinese rule in Tibet, something he is conspicuously unwilling to do. Riley is clear that the CIA cheated the Tibetans. Can he admit that Mao did so, too?

When principles clash

I’ve asked who benefits from portraying pre-PRC Tibet as a uniquely abusive society, who benefits from framing the invasion of Tibet as a ‘peaceful liberation,’ and who benefits from depicting Tibetan resistance as something foisted on Tibet by outsiders instead of growing organically from the conditions on the ground. The answer to all three is the same: China.

It should come as no surprise that these narratives were developed and promulgated by the PRC, which has sought for decades to portray the annexation of Tibet in a manner consistent with the self-professed values of a government dedicated to “socialism with Chinese characteristics” and a country which was repeatedly victimized during the colonial era. To borrow one of Riley’s lines from “The Guillotine,” Boots didn’t write out these lies, he’s just quoting them.

Of course the PRC wants to explain their occupation of Tibet as a civilizing mission and a war of liberation. Empires have always sought to justify their looting and plunder as somehow being compatible with their values, and claiming that occupation and domination are actually beneficial for those who have been subjugated is a classic refrain. Similar claims were made about China itself during the Japanese occupation, but I don’t see Riley racing to endorse them.

And of course independent Tibet has to be portrayed as uniquely abusive, because Beijing hopes that every abuse it claims of the old regime—real ones and exaggerated ones and entirely fabricated ones alike—will encourage people who believe in communism and anti-imperialism to allow their support of the former to overrule the latter. For every human rights abuse they’re documented committing in Tibet, Beijing feels the need to present an equal but opposite abuse from the past which they can claim to have stopped.

In reality, Tibet also produced its own iconoclastic thinkers and political figures who leveled serious criticisms against the old systems, people like Gendun Choephel and Phuntsok Wangyal. Their existence is deeply inconvenient for supporters of Chinese imperialism because they show that Tibet had the potential to reform itself from within, a possibility that Beijing cannot acknowledge if it wants to justify Chinese rule in Tibet as a necessity. The idea that an independent Tibet in 2023 would look identical to Tibet in 1949 is completely absurd, but Beijing desperately wants the rest of the world to take it as a given.

Reconciling principles

I was planning to close by encouraging Riley to read about Phuntsok Wangyal, the founder of the Tibetan Communist Party. To my surprise, Phuntsok Wangyal actually came up on Riley’s twitter feed while I was writing, although unfortunately not in a way that accurately reflects his story.

In response to Tibetans begging Riley to consider their perspective on the occupation of their homeland, Riley shared a tweet from Carl Zha, a Chinese podcaster who is a steadfast supporter of the Chinese occupation of Tibet. Zha had quoted Phuntsok Wangyal’s early criticism of the Ganden Phodrang government, but there’s much more to his story than that quote might suggest.

Phunwang, as he was known, grew up idolizing the Tibetans who defended their lands from Chinese invaders and became a fervent believer in communism. He pushed for an independent eastern Tibet and later for a socialist revolution in central Tibet, and when the PRC invaded he set aside his Tibetan nationalist ideals to help them overturn the old order. After the invasion Phunwang had outlived his usefulness to the Chinese authorities, however, and he was sentenced to 18 years in solitary confinement in a Chinese prison after warning the Chinese leadership that the actions of one of their officials in Tibet was likely to spark further conflict. With Tibet firmly under Chinese control, they had little need for a homegrown revolutionary who firmly believed in Tibetan rights.

The cruelty Phunwang endured during almost two decades in solitary confinement was handed out not by lamas or Tibetan aristocrats but by the Chinese Communist Party, which turned on him as soon as he displayed signs of being a “local nationalist,” an imperial euphemism if I’ve ever heard one. If even the Tibetans who supported reforms found themselves purged and imprisoned – and Phunwang was not the only one to suffer this fate – it becomes very clear that there’s more to this story than Beijing’s cheery propaganda about “serfs rising up” would suggest.

Perhaps Riley is simply irritated by the Dalai Lama or the existence of his institution. He’s free to cast his judgment, but it’s a mistake to let his opposition to one man blind him to the reality of what Chinese rule has entailed for the Tibetan people. Communism and anti-imperialism are at the center of Boots Riley’s politics, and they sit in contradiction here for Riley and others who hold these values. Attempting to square that circle by praising China’s annexation of a neighboring country is a betrayal of anti-imperialism and an attack on a subjugated people who deserve solidarity.

It’s the customary tendency of imperialists to put forward a claim to someone else’s land, and it’s the duty of anti-imperialists to judge that claim and find it lacking—regardless of whether or not it’s phrased in a way you find pleasing.