The terrorist attack of last week in Paris against the satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo is sparking a debate that goes beyond reflecting on the killings of innocent people for political or religious reasons.

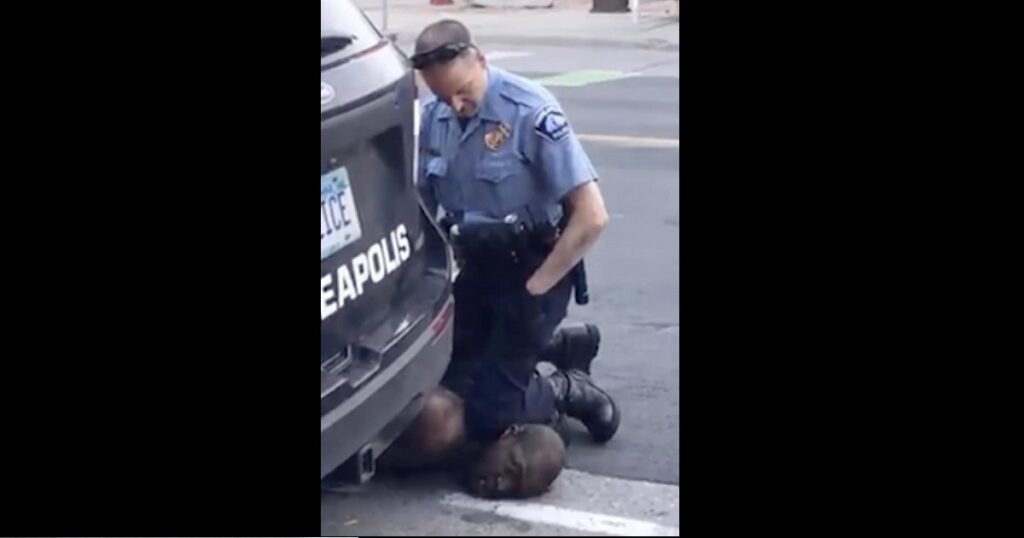

Unfortunately, the killings of innocent people as a result of different extremist ideologies happen every day and in huge numbers in many parts of the world.

Sometimes, the violence comes from individuals, sometimes it comes from organized armed groups, and sometimes it comes directly from authoritarian governments.

We should all remember that the loss of innocent lives is always unacceptable and we should learn to stay away from the moral double standards that the media inevitably impose on us by choosing which events (often tragedies) should deserve our attention instead of others.

Having said this, the genuine outpour of indignation and attention that has emerged as a result of the Paris terrorist attack has an objective basis. A satirical magazine represents the essence of freedom of expression in any free society, and to violently and brutally target its employees, as it happened in Paris, has raised the concerns of every citizen who is interested in protecting this right.

What is now becoming clear is that while the “international community” generally agrees to “condemn” this kind of violence, it has not yet agreed on the central issue that is at stake here: how to advance the fundamental human right of free expression for billions of people who do not yet enjoy it.

Globally, nation states have approached this issue with too many different laws and regulations, many of which are in direct contrast with the Universal Declaration of Human Rights approved by the UN General assembly in 1948 after a war that left millions upon millions dead after the rise of authoritarian ideologies.

Article 19 states:

“Everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression; this right includes freedom to hold opinions without interference and to seek, receive and impart information and ideas through any media and regardless of frontiers.”

The technological revolution of the last decades has made the visionary aspiration of sharing information “regardless of frontiers” a concrete daily possibility. In fact, the advent of the Internet makes it possible for everyone not only to express, but most importantly, to “seek, receive and impart information and ideas through any media and regardless of frontiers.” But this can happen only if one fundamental condition is met: that national governments do not censor the information that citizens are entitled to receive.

There are an increasing number of countries that explicitly limit this right by censoring media content available on the Internet. This is allowed to happen without serious challenges from the UN or democratic governments.

Pay attention, freedom of speech is the battleground chosen by extremists and authoritarian governments to change the way in which democratic societies operate.

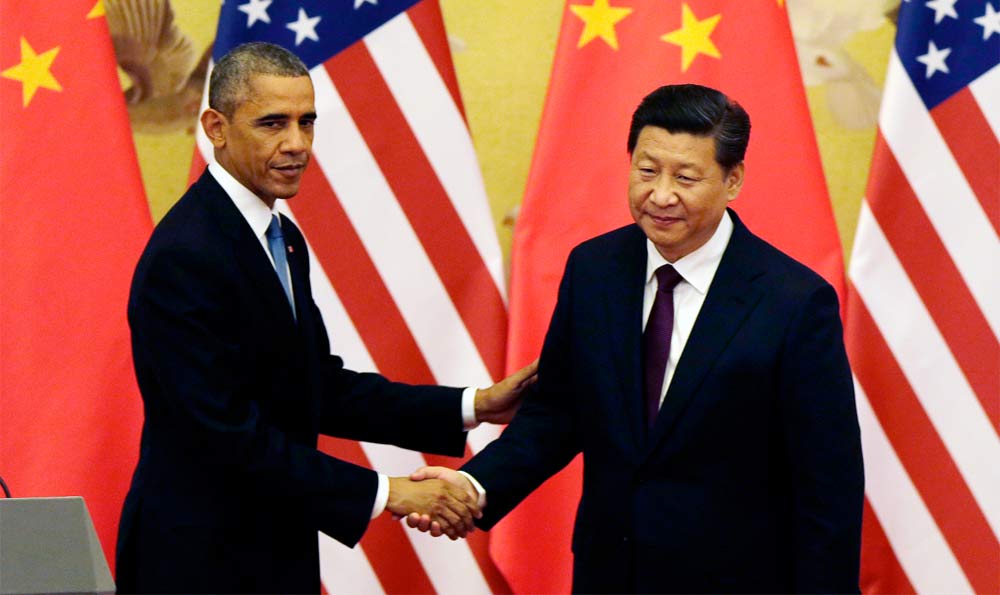

In fact, by focusing on “offensive”, “immoral” or “graphic” manifestations of freedom of expression, the goal is to intimidate and limit the right of the people to freely express themselves on sensitive political or social issues, as clearly emerged by the Chinese state news agency’s comment on the Paris attack.

The reasons are simple: the main enemy for any authoritarian government or extremist group is the people’s capacity to question or criticize its actions and motives. Imposing fear, and then silence, through violence, imprisonment, and torture are the means used to achieve this goal.

Democratic societies have ignored the importance of this issue for too long, and the future of freedom of expression cannot be left to Internet companies to negotiate or decide.

It is urgent for our countries to start publicly contrasting the measures that are taken by national governments to limit the right to access information through the Internet. China is leading this effort, having built a firewall and having set up a huge censorship machine, and putting pressure on Internet companies that want to do business in China.

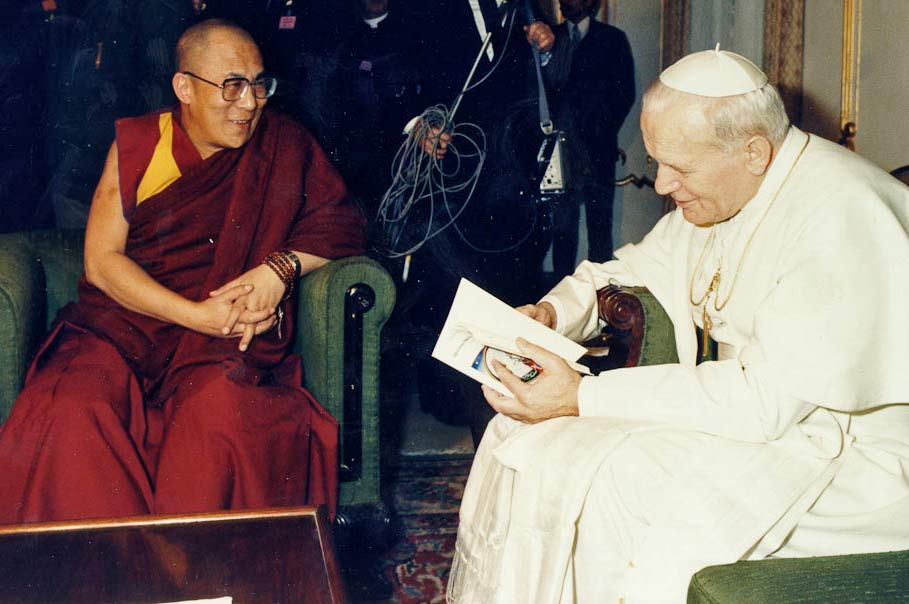

And this is why, even before the Paris attack, we were worried to see Facebook, a giant and global social media enterprise, deleting the post of a video of a Tibetan monk’s self-immolation (videos that are censored in China) citing “graphic” concerns regarding a purely political action; and that is why we decided to launch a petition to restore it that has now been signed by over 17000 people.

Worryingly, earlier this week, while meeting in Paris also a number of EU Ministers of the interiors called on Internet providers to increase their surveillance capacities.

This is the wrong path to follow. It is not by increasing censorship and controls on the general public, like China does, that terrorist attack will be prevented. This will only increase abuses. Experience tells us that a society is more secure when civil liberties are respected.

We at ICT are following very closely this debate. We do not want our societies to follow China’s censorship practices on the Internet and we are working to make sure that the opposite happens and that, one day, the flow of free information will break China’s firewall and reach the Chinese and Tibetan people.

Matteo