“On March 31, 1959, my party entered India. I have not been able to go back to my homeland since,” His Holiness the Dalai Lama writes somewhat poignantly about his dramatic escape from Tibet in his latest book, Voice for the Voiceless: Over Seven Decades of Struggle with China for My Land and My People (Harper Collins, 2025). Being published in the 66th anniversary of his escape and on his 90th birthday year. Through this book, His Holiness succinctly outlines his master plan for Tibet. Allow me to expand.

Master plans of the Dalai Lamas

First, the background. In the 1980s, during an interview with Tibetan Buddhist scholar Glenn Mullin (who later incorporated it in few of his books) the present 14th Dalai Lama shared his view about the previous Dalai Lamas having “master plans” in administrating their affairs. He surmised there was such plan that spread from the First to the Fifth Dalai Lamas, another that the Sixth Dalai Lama embraced, and one by the 13th Dalai Lama. His Holiness said the First to the Fourth Dalai Lamas expanded the sphere of their influence from southwestern Tibet to broader Tibet to make it possible for the Fifth Dalai Lama to assume overall leadership in Tibet. The Sixth Dalai Lama’s master plan was to alter the system of succession of the Dalai Lama, from reincarnation to blood lineage. Apparently, he wanted this change to do away with the power vacuum in the transition period between one incarnation and the next.

His Holiness the Dalai Lama looking at thangkas depicting the lives of the Dalai Lamas during his visit to Norbulingka Institute, India on March 9, 2017. Photo by Tenzin Choejor/OHHDL

The master plan of the 13th Dalai Lama was to make Tibet a modern state, a harmonious blend of temporal and the spiritual. He organized a monastic education system and bestowed ordinations to a large number of monks. He wanted significant administrative reforms, including social and political reforms like bringing modern education in Tibet. He was prophesied to live until his 80s (which would be in mid 1950s), but it is believed that he foresaw the dangers ahead from the imminent Chinese Communist invasion and the need for a Dalai Lama to be of age to meet the challenge. Therefore, it is believed that he chose to pass away in his fifties.

Having expanded on his predecessors thus, the present Dalai Lama told Mullin, “Perhaps I will have to come up with some fourth master plan.” Although His Holiness does not say so, my contention is that Voice for the Voiceless reflects his master plan for Tibet?

His Holiness begins by giving an overview of the historical developments of Tibet’s ties with China and India, two countries that significantly impact the Tibetan people even to this day. This includes Chinese Communist invasion of Tibet, his efforts from Lhasa, as well as during his visits to China and India in the mid-1950s, to find peaceful co-existence and subsequent escape to exile in India in 1959. These are laid out in more detail in his two memoirs, My Land & My People and Freedom in Exile.

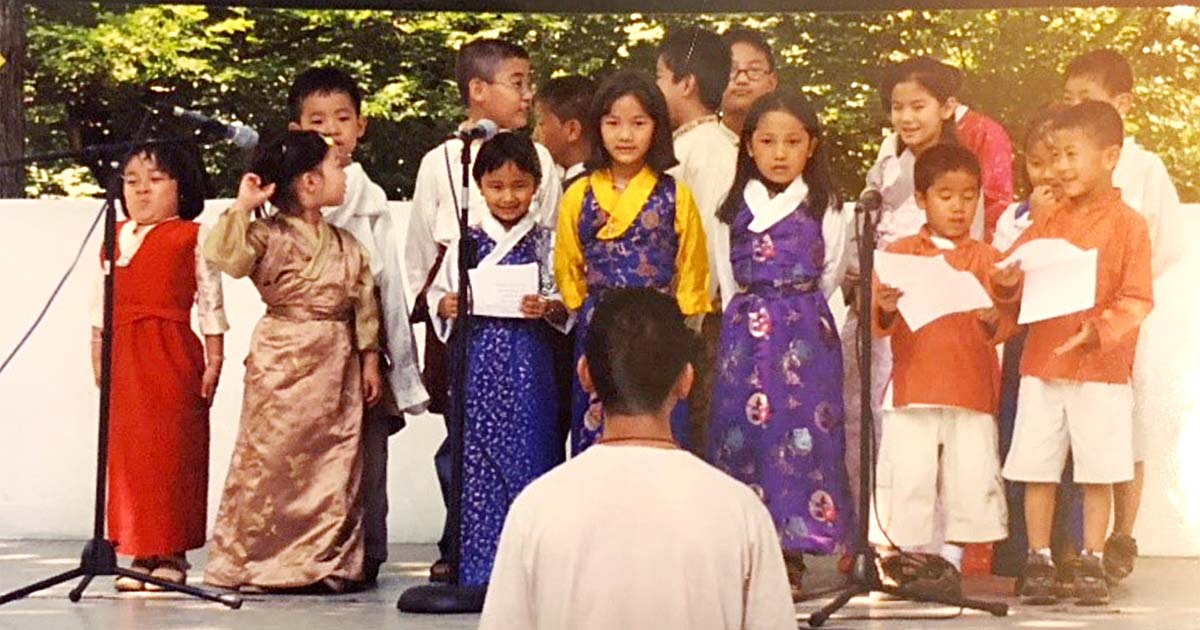

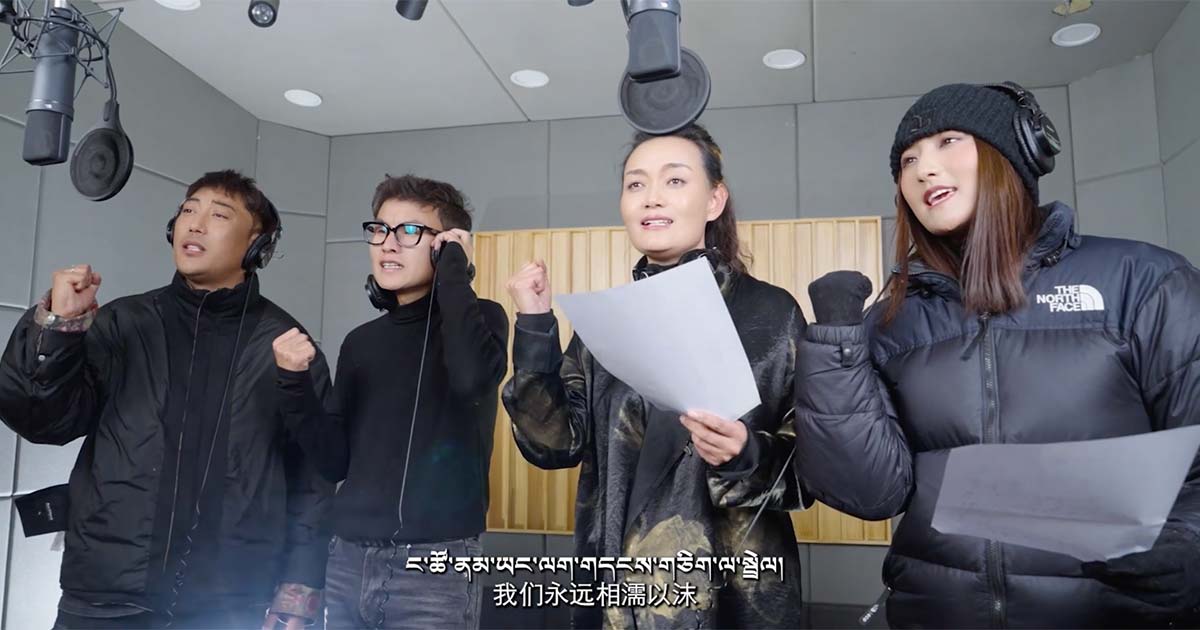

Then, His Holiness outlined the challenge, recalling his public statement in 1960, saying, “On that first anniversary [of the Tibetan National Uprising of March 10, 1959], I stressed the need on our part to adopt a long-term view of the situation of Tibet. I said that for those of us in exile in a free country, our priority must be ensuring the survival of our civilization, especially through the protection of our distinct language and cultural traditions. I assured my people that truth, justice, and courage would be our weapons and that we would eventually prevail in our struggle for freedom.” He even went so far as to say, “Ours is an existential crisis: the very survival of an ancient people, their culture, language and religion is at stake.”

Having outlined the challenge, His Holiness’ plan for addressing the issue of restoration of Tibetan independence was two-pronged: “to remind the world of what happened and what was still happening in Tibet and to care for the Tibetans who escaped with me to freedom.” The book details his outreach to the international community, particularly the United Nations. There is a whole chapter on outreach to Tibet supporters with a Buddhism-inspired headline, “Reaching Out to Our Fourth Refuge”.

Beginning in the seventies, His Holiness turned his attention to direct dialogue with the Chinese Government to address this challenge. In this, as outlined in the chapter “Overtures Toward a Dialogue” His Holiness felt we needed to consider not only the Tibetan aspirations but also “to take into account seriously the perspective of the Chinese side.” Thus, “The seed was sown for what later came to be known as the Middle Way Approach—seeking not independence but genuine autonomy within the framework of the People’s Republic of China.”

His Holiness outlines the initiatives from the late 1970s, including his Five Point Peace Plan in 1987, the Strasbourg Proposal in 1988, “up until 2019, I did maintain informal and at the time confidential contacts with Beijing leadership through individual Chinese.” I myself was privileged to be part of this process, including being a member of the team that engaged with the Chinese authorities from 2002 to 2010.

H.H. the Dalai Lama outlining his proposal for future Tibet at the European Parliament in Strasbourg in June 1988

Next Dalai Lama will be born in the free world

As is the nature of the Tibetan system, His Holiness’ master plan also crossover into the spiritual realm.

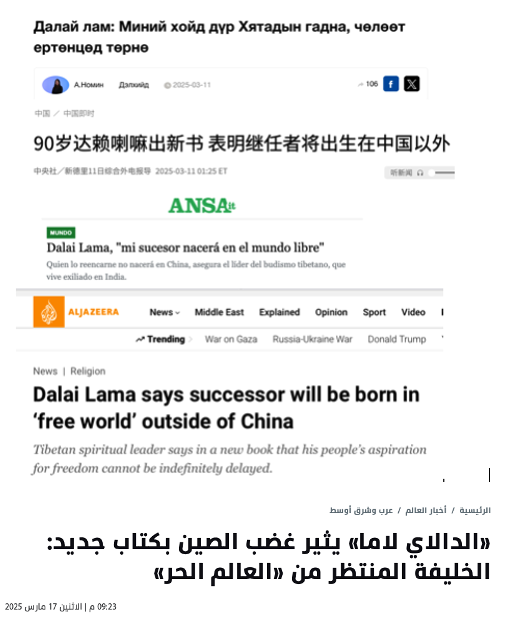

One section of the book that has garnered international attention is the reference to the next Dalai Lama. The relevant sentence is this, “Now, since the purpose of a reincarnation is to carry on the work of the predecessor, the new Dalai Lama will be born in the free world…”

Media coverage in Mongolian, Chinese, Italian, English and Arabic on HH the Dalai Lama’s reincarnation reference in his new book

He prefaces this by referencing his 2011 statement on reincarnation conditioning the coming of the next Dalai Lama to whether the Tibetan Buddhists see benefit. If so, he had said it will be his Gaden Phodrang Trust (the Office of the Dalai Lama) that will have the sole authority on search and recognition. The spiritual element is further emphasized by his reiteration that the process should include “consulting the oath-bound Dharma protectors historically connected with the lineage of the Dalai Lamas, as was followed carefully in my own case” and also “that I will also leave clear written instructions on this.”

In the Tibetan Buddhist system, Palden Lhamo is one such Dharma protectors who is believed to have pledged to particularly stand beside the Dalai Lamas. Invocation of Palden Lhamo is a familiar ritual in the Tibetan community in exile and she is believed to be able to provide visions, including in the search of the Dalai Lamas. The present Dalai Lama considers Palden Lhamo as someone close to him. During a Long-life Offering to him in Dharamsala on June 11, 2024, the Dalai Lama told the gathering, “I have dreamt of Palden Lhamo sitting on my shoulders and telling me that I would live to be a hundred years old or more.”

One update this book has on the reincarnation, since his 2011 statement, is that His Holiness has “received numerous petitions and letters from a wide spectrum of Tibetan people—senior lamas from the various Tibetan traditions, abbots of monasteries, diaspora Tibetan communities across the world, and many prominent and ordinary Tibetans inside Tibet—as well as Tibetan Buddhist communities from the Himalayan region and Mongolia, uniformly asking me to ensure that the Dalai Lama lineage be continued.” Thus, in accordance with his 2011 statement, His Holiness is expected to issue some statement this year on the future course of action.

Irrespective of any development this year, His Holiness draws this conclusion on the connection between the institution of the Dalai Lama and the Tibetan issue: “Some might think, given my age and Communist China’s position as a global power today, that time is not on our side. I disagree. Yes, the Dalai Lama institution plays today an important role in unifying Tibetans everywhere, but let us not forget that while the Dalai Lama institution is only five hundred years old, Tibet’s history is older by more than a millennium and a half. So, I have no doubt that our struggle for freedom will go on, for it pertains to the fate of an ancient nation and its people. As an inherently unstable system, totalitarianism definitely does not have time on its side. Time is on the side of the people, Tibetans as well as Chinese, who aspire for freedom.”

Survival of Tibetan identity and Broken promises from the Chinese side

So, how does His Holiness view the effectiveness of his master plan? In recent years, in his public remarks, he has repeatedly talked about his contribution. Most recently, during an offering of Long-life Prayers in Dharamsala on March 6, 2025, His Holiness summed up his contribution saying, “As you have seen, I have been able to benefit the people of the world to a good extent. In addition, I feel I’ve been able to help Tibetans both inside Tibet and in exile with advice and instructions I have given sincerely.”

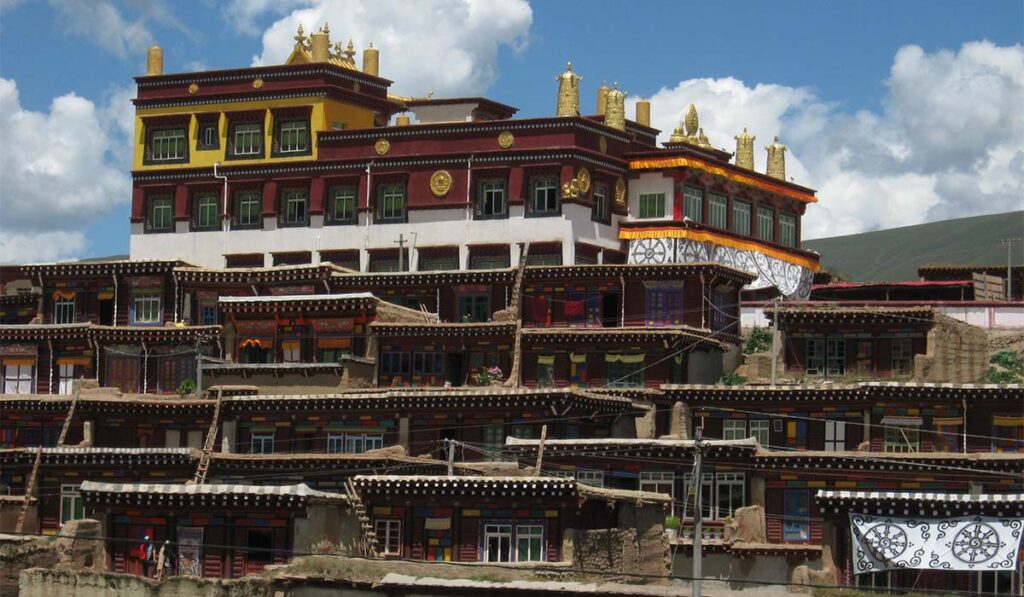

The book details the reestablishment of the “historically important cultural and religious institutions of Tibet”, and the establishment of Tibetan refugee resettlement camps as well as many new institutions that complimented the changed situation of Tibetans. All in all, Tibetan identity, religion and culture survives in exile. In comparison, in Tibet, His Holiness says, “the repressive policies on the ground targeting Tibetan identity, culture, and traditions, as well as the large-scale demographic change taking place on the Tibetan plateau caused me great alarm, compelling me to say that what was happening inside Tibet was either willingly or unwillingly, a form of cultural genocide.”

The book clearly shows His Holiness’ disappointment with Chinese leadership at different stages to his overtures for a mutually beneficial negotiated settlement of the Tibetan issue.

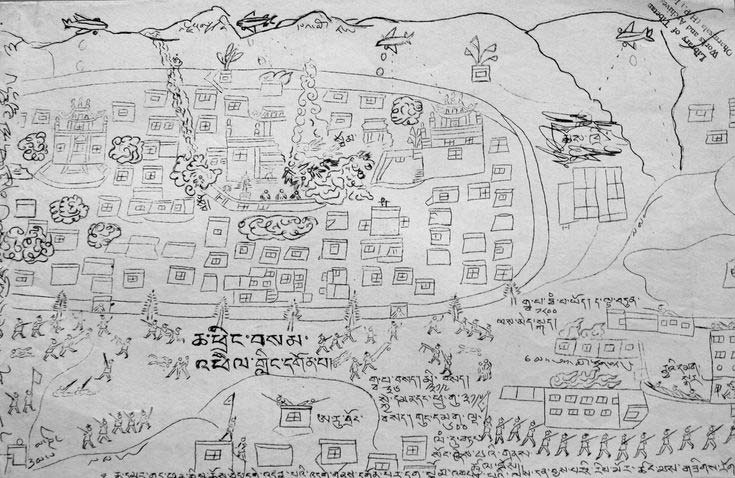

In the aftermath of his visit to Chinese capital Beijing in 1954-55 and meetings with Mao Zedong when commitments were made to preserve Tibetan autonomy under a new political system, the book says, “The promises and assurances received in Beijing turned out to be empty.” Similarly, during his visit to India in 1956 he had received commitments from then Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai who was also in India, but “Chinese pledges; Zhou was simply lying.” His Holiness includes a Tibetan quote with which he seems to be agreeing, “There is an old Tibetan saying that captures the essence of the relationship between the Tibetans and the Chinese: “Tibetans are let down by their hopes; the Chinese are let down by their suspicions.”

The Dalai Lama (first right) with Mao Zedong, the Panchen Lama and Zhou Enlai at the Tibetan new year reception he hosted in Beijing in 1955

It is also interesting to see His Holiness take a philosophical perspective on the Tibetan issue. He says, “Tibet and its people were the victims of tragic circumstances of history.” This is because the major powers that had historic connections with Tibet were all preoccupied during the crucial period. Similarly, in his advice to the Tibetan people (in the last section of the book), His Holiness says, “Today’s dark period of Communist Chinese occupation may seem endless, but in our long history, it is but a brief nightmare. As our Buddhist faith teaches us, nothing is immune to the law of impermanence.”

He concludes, “At the time of publishing this book, I will be approaching my ninetieth year. If no resolution is found while I am alive, the Tibetan people, especially those inside Tibet, will blame the Chinese leadership and the Communist Party for its failure to reach a settlement with me.”

Given that this book is about what the Dalai Lama has done for Tibet, much of what is in it is a matter of public record. However, it expands on the thought process on some of the decisions taken, whether it is about not accepting the Chinese invitation in the wake of the death of the 10th Panchen Lama or when the 13th Dalai Lama left an extraordinary and prophetic warning of Communist incursion from the east, way back in 1932. “Tragically, the regency and the Tibetan leadership, following the Thirteenth Dalai Lama’s death, failed to grasp the urgency and seriousness of his warning. Pretty much every aspect has proven to be precisely correct.” Is there a similar message here by him to the present Tibetan leadership and community?

In one sense, this book could be seen as the last of its kind from His Holiness the Dalai Lama given that he had devolved his political authority in 2011 and his age. We are unlikely to see any such writing of this scale in the future by him. China has shown through its policies that its plan is to annihilate the Tibetan identity through Sinicization. The present Dalai Lama’s master plan is to continue the work of the 13th Dalai Lama and to build on it. His objective was to enable Tibetan identity to survive eventually in Tibet, while preserving it in exile. By becoming the voice for the voiceless Tibetans under Chinese communist rule, this book shows how the Dalai Lama has been able to achieve that.

Be that as it may, I believe the final chapter of the present Dalai Lama’s life is yet to be written.

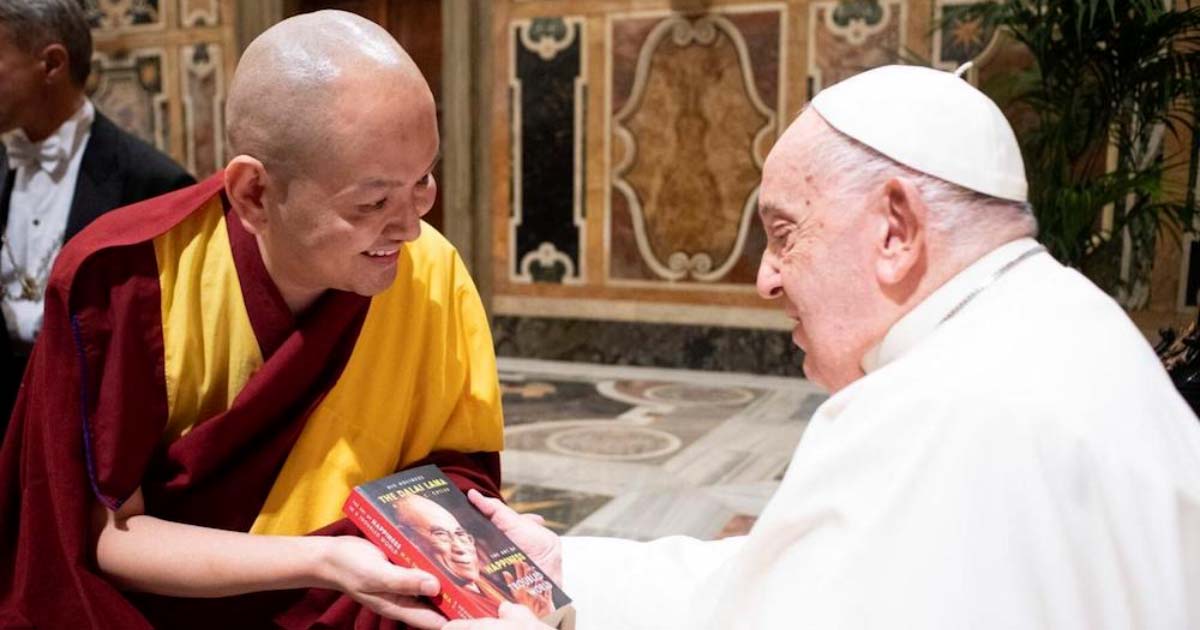

The third initiative was in the form of a book, Our Wish-fulling Gem Part 2: A Biography of His Holiness the Dalai Lama” (Library of Tibetan Works & Archives, Dharamsala, 2025), by educationist Chophel compiling the details on visits by His Holiness the Dalai Lama throughout the world outside of India from 2011 till 2018. Additionally, this second volume also has details on His Holiness’ visits within India from 2011 onwards. As in the first volume, in this book, too, the author provides an overview of His Holiness’ meetings and remarks at events big and small in different countries which are “a testament to the enduring influence of one of the world’s most revered spiritual figures.” His first volume,

The third initiative was in the form of a book, Our Wish-fulling Gem Part 2: A Biography of His Holiness the Dalai Lama” (Library of Tibetan Works & Archives, Dharamsala, 2025), by educationist Chophel compiling the details on visits by His Holiness the Dalai Lama throughout the world outside of India from 2011 till 2018. Additionally, this second volume also has details on His Holiness’ visits within India from 2011 onwards. As in the first volume, in this book, too, the author provides an overview of His Holiness’ meetings and remarks at events big and small in different countries which are “a testament to the enduring influence of one of the world’s most revered spiritual figures.” His first volume,