The potshots from Liu came in response to criticism two of Hollywood’s most prominent directors—Quentin Tarantino and Martin Scorsese—made of the “Marvel Cinematic Universe,” of which Liu is a proud part. In an interview that premiered in November, Tarantino said Marvel’s stable of actors are “not movie stars.” “Captain America is the star,” he said. “Or Thor is the star.” It’s worth noting that Anthony Mackie, who actually plays Captain America, said much the same thing years ago. But Liu evidently felt he is a star and wanted the world to know it.

As for Scorsese, the eminent helmer of “Taxi Driver” and “Raging Bull” helped kick-start this whole controversy in 2019 when he told a British magazine that Marvel’s cinematic universe is “not cinema.” Scorsese elaborated: “It isn’t the cinema of human beings trying to convey emotional, psychological experiences to another human being.”

Scorsese is likely the most famous and accomplished director of English-language cinema in the world today. But that didn’t shield him from the ire of Marvel fans, who apparently felt they understood film better than the man who earned the American Film Institute’s Life Achievement Award in 1997. With his now wisely deleted tweet, Liu showed himself to be just as presumptuous.

There are so many things wrong with what Liu wrote. To begin with, Scorsese absolutely has the right to “point” his nose at others working in his form (I am not as familiar with the movies of Tarantino and am not here to defend him). A master in any field has the prerogative to critique an upstart.

There’s also Liu’s confusion about auteurism—a rare breed of filmmaking that expresses the personal vision of the director—versus the assembly-belt production of Marvel Studios. Liu basks in leading a “$400 million plus movie,” but he and Scorsese are after different goals. More on that later.

“Kundun” left unsaid

But the most egregious part of Liu’s remark was its obliviousness. He followed up his ill-conceived initial tweet by defending Marvel on the grounds of inclusion. “No movie studio is or ever will be perfect,” he said in another now-deleted tweet. “But I’m proud to work with one that has made sustained efforts to improve diversity onscreen by creating heroes that empower and inspire people of all communities everywhere. I loved the [Hollywood] ‘Golden Age’ too.. but it was white as hell.”

There’s no disputing the first or last part of that comment. But in the middle, Liu was being either embarrassingly ignorant or willfully deceitful. Perhaps he didn’t know—or didn’t want to acknowledge—“Kundun,” Scorsese’s sublime biopic about the current Dalai Lama of Tibet. “Kundun” just had its 25th anniversary last month, yet it remains one of the least seen, least accessible titles in Scorsese’s legendary filmography. That’s no accident: Disney, the same company that now owns Marvel, has deliberately tried to keep “Kundun” out of public view for the past quarter century.

Actually, Disney’s attempts to bury “Kundun” began even before its release date. In the 1990s, China was not the box office behemoth it has since become. The People’s Republic had only begun to open its market to foreign studios when Disney innocently went into production on “Kundun,” not realizing the furor it would provoke among Chinese authorities. But once China’s government started pulling Disney films and series from the country, Disney CEO Michael Eisner reportedly promised Chinese officials that “Kundun” would “die a quiet death.” He even recruited former Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, an alleged war criminal, to assure the Chinese that Disney wouldn’t aggressively promote the movie and that it would bomb at the box office.

“Kundun” premiered in the United States on Christmas Day 1997. It brought in just $72,000 in its opening weekend, ultimately finishing with a total gross of $5.7 million. The following year, Eisner traveled to China, where he apologized to government officials for releasing “Kundun,” saying it was “a stupid mistake.” According to the records of China’s former Premier Rongji Zhu, Eisner groveled:

“[W]e released the film in the most passive way, but something unfortunate still happened. The film was a form of insult to our friends and it cost a lot of money, but other than journalists, very few people in the world saw it. The bad news is that the film was made; the good news is that nobody watched it. Here I want to apologize, and in the future we should prevent this sort of thing, which insults our friends, from happening. In short, we’re a family entertainment company, a company that uses silly ways to amuse people.”

Twenty-five years later, that’s still what Disney is, despite Liu’s self-important claims about “creating heroes that empower and inspire people of all communities everywhere.” (As a CBR headline wisely puts it, “Simu Liu Sided with the Wrong Gatekeepers in His Tarantino Response.”)

Continued erasure

Although Eisner is long gone, the current leadership at Disney is no less dedicated to ensuring that as few people as possible see “Kundun.” The studio has pumped a fortune into Disney+, but “Kundun” is not available there, and as far as I can tell, it’s not on any other streaming service either. I am a cinephile; watching great movies is an important part of my life. I am even part of a film group that gets together every month to discuss a classic movie. But we probably couldn’t add “Kundun” to our lineup because most group members wouldn’t be able to stream it. (Thankfully the good people at Kino Lorber offer a special edition Blu-Ray and DVD of the film. Link below.)

Disney’s effacement of the Tibetan people is not limited to the Dalai Lama and “Kundun,” however. In 2016, the Marvel Cinematic Universe gained a new main player with the release of “Doctor Strange,” yet another superhero spectacle. In the comic books, Doctor Strange learns his magic powers from the Ancient One, a Tibetan sage. But in the movie, the Ancient One is a Celt played by Tilda Swinton, a White actress from Scotland. Although Disney claimed it was trying to avoid a stereotypical portrayal of Asians, the screenwriter, C. Robert Cargill, shockingly admitted, “If you acknowledge that Tibet is a place and that [the character is] Tibetan, you risk alienating 1 billion [Chinese] people.” In contemporary discourse, I think that’s called erasure.

Marvel’s attempt to hide its invisibilizing of Tibetans behind false concerns of racism set the stage for Liu to brandish racial injustice to ballyhoo his own success and bodyguard the studio that pays him. That’s one of the things that annoyed me most about his tweets. As a person of color, I do not see “Shang-Chi and the Legend of the Ten Rings” as some breakthrough, even though Liu obviously does. As a South Asian, I also couldn’t care less about “Ms. Marvel” or “Eternals,” both of which feature actors born in Pakistan. Instead, I’d rather watch the enriching cinema of the late Bengali auteur Satyajit Ray or the 2020 Marathi movie “The Disciple,” which is now streaming on Netflix. And I appreciate what I’ve seen from the Tibetan director Pema Tseden. Such films are the “cinema of human beings trying to convey emotional, psychological experiences to another human being.”

When Liu says that he “would never have had the opportunity to lead a $400 million plus movie” with Scorsese and Tarantino as gatekeepers, he’s in effect saying that people of color should have the same freedom as Whites to create trashy, dehumanizing entertainment. I suppose that’s only fair, but I’d like to think we can all set our sights a little higher.

Purifying effect

Warning: Spoilers ahead.

“Kundun” is a perfect example. There are no superhuman powers in the film; instead of pummeling his adversaries into submission, the Dalai Lama tries to negotiate with them, which he continues to do to this day.

There also isn’t any whitewashing. All the Tibetan characters are played by Tibetans. And rather than use a Western intermediary to guide the audience through the story, Scorsese and screenwriter Melissa Mathison—a late ICT Board Member—throw us right into the family home of Lhamo Dhondrup, a 2-year-old boy in a Tibetan outskirt who would soon be recognized as His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama. From there, we see how the young reincarnate and his people lived their traditional lives before Communist China swallowed their homeland.

Shot on a budget of $28 million (still only about 1/8 of “Shang Chi’s” budget in today’s dollars), the movie generates more power and suspense in one roughly 15-minute sequence showing His Holiness’ escape to India than any green-screen battle Marvel has ever programmed into existence. Soundtracked by Philip Glass’ hypnotic score and edited by Scorsese’s longtime collaborator Thelma Schoonmaker, this climax of the film envisions the Dalai Lama’s perilous route to freedom as a sermonic spiritual journey.

That finale alone makes “Kundun” worth watching. Yet some of the moments that have stuck with me most are the quieter, more pacific recreations of the old Tibet. One scene that has a purifying effect on my mind involves the 5-year-old Dalai Lama playing with toy soldiers, the way any child might. His Holiness throws his figures at the soldiers of his playmate: a sweeper working in the Potala Palace. “I have more men!” he thunders. “I have smarter men,” the sweeper calmly replies, pulling the boy’s soldiers toward him. “I have all the men.” The Dalai Lama slumps. “Today you lose, Kundun. Tomorrow you may win,” the sweeper says as the camera zooms in. “Things change, Kundun.”

Need for preservation

It is this ancient culture of wisdom that all of us in ICT’s community of compassion and the wider Tibet movement are trying to preserve. That vital heritage has already been fractured by China and its assimilationist regime. But it has also been swept away by shameless corporations like Disney and Marvel, which will sacrifice anything of artistic or spiritual value at the altar of the almighty buck.

After 25 years, a film like “Kundun” would never even make it into production today. Instead, we get junk like “Shang Chi” and whatever the latest intellectual property iteration is from Disney and its brethren. But as our lives grow ever more digitized and soulless, we should seek out and preserve great art like “Kundun.” And as the modern world leads us further astray from compassion and nonviolence, we need the wisdom of the Dalai Lama, captured so expressively in “Kundun,” now more than ever.

Buy “Kundun” on Blu-Ray or DVD from Kino Lorber!

The Dalai Lama’s wisdom is also on vivid display in the soon-to-be-released book, “Heart to Heart,” illustrated by Mutts’ cartoonist Patrick McDonnell. Proceeds from the book will benefit ICT. Preorder your copy of “Heart to Heart” today!

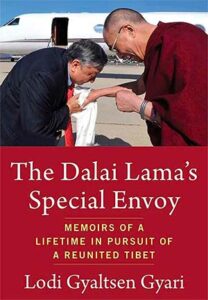

Even though Rinpoche, as he is reverently addressed by people in the Tibetan cultural world, is no longer with us, his legacy lives on and is a daily reminder to many of us at ICT who knew him. Now, a book that he had been working on since his retirement has been published by the Columbia University Press. It is aptly titled,

Even though Rinpoche, as he is reverently addressed by people in the Tibetan cultural world, is no longer with us, his legacy lives on and is a daily reminder to many of us at ICT who knew him. Now, a book that he had been working on since his retirement has been published by the Columbia University Press. It is aptly titled,