By Katerina Bursik Jacques

On Dec. 18, 2011, ten years ago, Václav Havel passed away. Czech human rights advocate Katerina Bursik Jacques writes about the extraordinary friendship between the Czech president and the Dalai Lama. Photo: Zdenek Merta.

Human rights are universal and indivisible. Human freedom is also indivisible: if it is denied to anyone in the world, it is therefore denied, indirectly, to all people. This is why we cannot remain silent in the face of evil or violence.

-Václav Havel, “Summer Meditations,” 1991

In Czechoslovakia, 1989 began with police arrests on Wenceslas Square in Prague during a low-key commemorative event, marking the death of student Jan Palach who, in January 1969, had burned himself to death, in protest against the occupation of Czechoslovakia by Warsaw Pact troops, in an attempt to rouse a society that was descending into apathy. Among those arrested was playwright and leading Czechoslovak dissident Václav Havel, for whom this was nothing new. He had served more than four years in prison in the past. There was no indication in January that 1989 would become a year of ‘miracles’ that would bring freedom to the entire Soviet bloc and make the imprisoned dissident Havel president before the year was out.

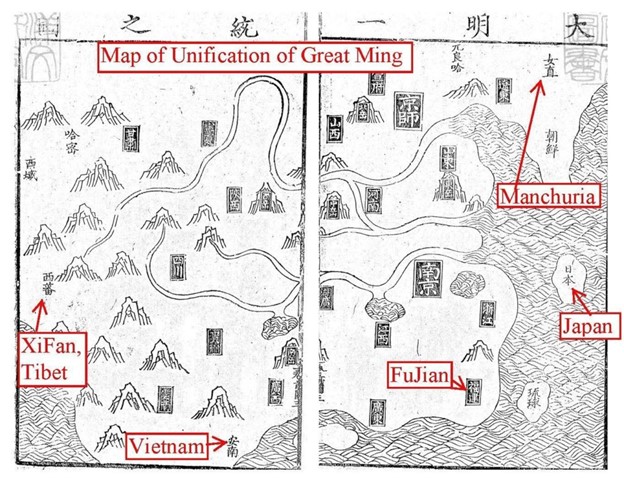

Virtually no one knew—and not only in Czechoslovakia—that martial law had been declared in the Tibetan capital, Lhasa, in March 1989. But when, a few months later, at the beginning of June, images of the brutal crackdown in Tiananmen Square in Beijing were circulated around the world, the public was badly shaken. At the sight of tanks targeting defenseless young people, Czechoslovak citizens also felt solidarity and anxiety, as it recalled their own humiliation in 1968 when Soviet tanks had arrived on the streets of Prague.

During the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia, Czechoslovaks carry their national flag past a burning tank. Photo: Wikimedia Commons.

In August 1968, brute force had dashed any hopes of freer conditions in the country. In Czechoslovak cities, streets were aflame, and people were injured and died. Twenty years of so-called ’normalization’ followed, during which the Czechoslovak public (except for a small group of convinced Communist ideologues or opportunists who profited personally from Soviet influence) regarded the Soviet Union, whose regime they despised, as their greatest enemy. The topic of a remote Communist China was somehow beyond the European horizon at the time—most people, apart from insiders, were not interested.

But it was the Tiananmen Square massacre in June 1989 that shocked the world. It reminded everyone that there was another totalitarian power besides the Soviet bear —Communist China, which did not hesitate to send in the army against its own people and inflict a bloodbath on them, even in front of media cameras. The nature of the Chinese Communist regime, in all its monstrousness, was thus suddenly visible to anyone who wished to see. Tiananmen resonated in Czechoslovakia too and only served to reinforce the sense of disgust with Communism and a degree of hopelessness about the future.

A fateful encounter

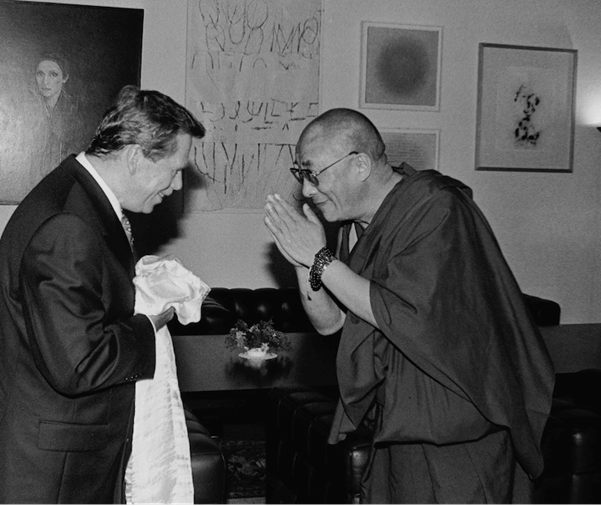

The first fateful connection between Václav Havel and His Holiness the Dalai Lama was on Oct. 5, 1989, the day of Havel’s birthday, and also the date on which the annual Nobel Peace Prize was to be announced. Václav Havel was about to celebrate his birthday with friends, but he had to be on the alert. As in previous years, he was on the shortlist of candidates for the prestigious prize and had to be prepared to answer questions from foreign journalists (their Czechoslovak counterparts were certainly not interested in such a thing; they may even have been terrified at the thought of having to report on an award to a prominent opponent of the regime …). According to witnesses, the first person to inform Václav Havel that the prize had been awarded to the Tibetan Dalai Lama was a journalist from Reuters. Havel’s response in English was brief and typical for him: ‘He deserves it!’ Later, the Dalai Lama made the same remark about Havel.

Although there were plenty of reasons in 1989 why Havel should finally have been awarded the most important human rights prize of all, the situation of the Tibetans was more arduous than that of the Czechoslovaks, and the massacre in Beijing certainly contributed to the choice of the Dalai Lama, who was both a symbolic victim of Chinese Communist subversion and an embodiment of its antithesis, the policy of nonviolence.

Moreover, nonviolence was also what Havel symbolized. Both were prominent representatives of their occupied nations, one a dissident and prisoner of conscience, the other a political exile who had lost his homeland. For their compatriots, they were moral authorities who kept alive the hope of freedom and a life of dignity, however unimaginable it was on that October day. Without being acquainted with each other or knowing much about each other, they were already linked by the similarity of their personal fate and the parallels between their peoples.

The Czechoslovaks and Tibetans both experienced firsthand subjugation and military occupation, coupled with the loss of fundamental freedoms—the elimination not only of political and civil rights, but also of culture and religion, combined with censorship and a pervasive state ideology. In both Czechoslovakia and Tibet, the occupying regimes imposed a harsh materialist doctrine that deprived individuals of their creative potential and their religious and spiritual dimension. The Communist ideal of the human being was—and is—in stark contrast to what the monk Dalai Lama and citizen Václav Havel represented.

Czechoslovaks and Tibetans mirrored each other’s experiences not only of foreign occupation but also of government-in-exile. The Dalai Lama created his shortly after escaping to India, the Czechoslovaks created theirs in London during the Second World War. And both in Czechoslovakia and among Tibetans there were individuals who shouldered the burden of the moral dilemma and made themselves individually the loudest voice of conscience of their people, the so-called burning torch.

In October, neither Havel nor the Dalai Lama could have foreseen the changes that would take place in a few weeks’ time. However, events gathered momentum quickly, and the fall of East Germany’s Berlin Wall in November was followed by demonstrations in Czechoslovakia and the so-called Velvet Revolution, which, apart from the initial violent clash between armed security forces and students on Nov. 17 in Prague, took an unexpectedly smooth course, inadvertently materializing Havel’s ideal of nonviolence.

When His Holiness the Dalai Lama received the Nobel Peace Prize at a ceremony in Oslo on Dec. 10, Human Rights Day, the Velvet Revolution was already in full swing. Havel was at the center of the action and was somehow naturally heading for the presidency.

One of those who participated in nominating the Dalai Lama for the Nobel Prize and who also attended the award ceremony in Norway was a former Indian diplomat in Prague, a supporter of the democratization process in Czechoslovakia and a supporter of the Tibetan cause, Mr. Manohar Lal Sondhi. He decided to connect his idols, the Dalai Lama and Havel. Before returning to India from Oslo, he stopped in revolutionary Prague, where he visited the Civic Forum office to convey the Dalai Lama’s wish “that Czechoslovakia become a centre of peace in Europe” together with a personal message to Václav Havel. In return, Mr. Sondhi then took to India a greeting from Mr. and Mrs. Havel to the Dalai Lama. He thus became one of the driving forces behind the events surrounding the Dalai Lama’s historic visit to Prague.

First time in Czechoslovakia

On Dec. 29, 1989, six weeks after the outbreak of the Velvet Revolution, Václav Havel was elected president amid general euphoria. A few days later, millions of Czechoslovak households were watching his New Year’s message on television screens. Havel began his speech by stating that the citizens had been lied to for decades, and that he had not been elected president in order to lie to them too. According to Havel, truth and love were supposed to triumph over lies and hatred. Empty Communist platitudes about class struggle and happy tomorrows were replaced by truthful words from President Havel about the poor state of society and a proposal for the direction a free country should take together with the policies it should pursue. In his speech, Havel formulated the values on which the new democracy was to be based.

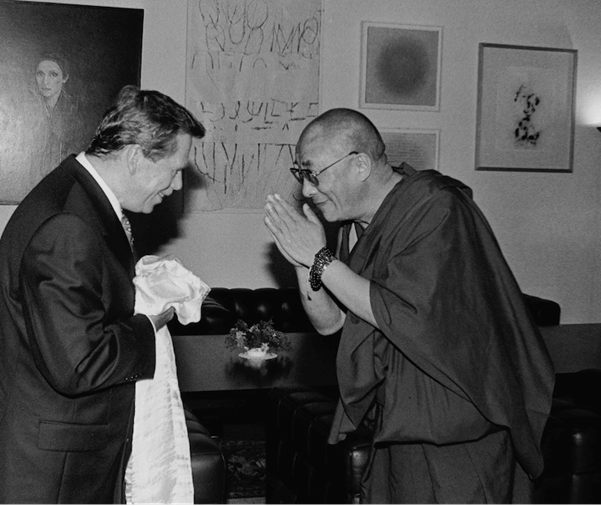

Václav Havel welcomes the Dalai Lama in Prague. Photo: OHHDL.

And surprisingly for some, Havel concluded his television appearance by expressing his wish that Czechoslovakia be visited as soon as possible by two important spiritual authorities, the Catholic Pope John Paul II and the Tibetan Dalai Lama. As a man not firmly anchored in religion, but deeply grounded philosophically and spiritually, Havel understood the value of “interreligious dialogue,” which he publicly encouraged and later fully developed at the FORUM 2000 conferences, of which the Dalai Lama later became a regular guest and an integral part.

In his speech, Havel said verbatim that he would be “happy” if they both came, even if only for a single day. It’s obvious what he meant: restoring spirituality in a society which had been distorted by “historical materialism” and was spiritually arid. Later, when Havel recalled the Dalai Lama’s first invitation to Prague, he spoke about how the Dalai Lama had brought a little bit of light into our midst for a time. And witnesses confirm that this was indeed the case.

Apart from the spiritual motivation for both invitations, there was also a political aspect, of course. John Paul II was known for his opposition to Communism and his sense of human rights, and his arrival signaled not only the return of religious liberties to Czechoslovakia, but also the end of the Communist ideology in Central Europe. Likewise, the Dalai Lama, as the spiritual leader of Tibet, was also the foremost representative of a hard-pressed nation, who carried the hopes of his people on his shoulders. The Dalai Lama and the Pope arrived in Prague on Feb. 3 and April 21, 1990, respectively.

In retrospect, the Dalai Lama’s entire visit to Prague seems like a small miracle, when one considers that it took place only a month after Havel introduced the idea. On the Czechoslovak side, there was no experience of diplomatic protocol, and those who were present recall that everything happened somewhat chaotically. At a time when there were no mobile phones or the internet, and it was not possible to buy a ticket with just a couple of clicks on a computer as it is today, it was also an extraordinary organizational feat on the part of the Tibetans. Havel’s office prepared a three-day program, which in practice was modified in various ways and consisted of a series of public appearances, impromptu meditations and meetings with the general public, who turned up at various points to see and greet the distinguished guest. The most important of these meetings was the initial audience of the Dalai Lama with Cardinal František Tomášek in the Archbishop’s Palace at Prague Castle, and especially the meeting with Václav Havel himself at Lány Castle.

Few people in Czechoslovakia had any clear idea about the Dalai Lama, rather just a vague notion of what and whom he represented and that he was a recent Nobel Peace Prize winner. Apparently, not even Václav Havel knew exactly what to expect. In this connection, he later remarked that at that time his “knowledge of Tibet and its brave inhabitants was almost entirely from books.”

As both men recall, and as eyewitnesses testify, their first meeting was warm and, in a sense, surprisingly informal from the very outset. People described the intimacy that developed between the two men almost immediately. Both had a pleasantly detached approach to their functions and roles, both were informal and both liked to laugh. The Dalai Lama appreciated Havel’s sense of humor, humanity and naturalness. Havel, too, was pleasantly surprised by the warmth and directness of the holy man, who had a ready wit and a broadminded assessment of worldly transgressions. He told Havel, a heavy smoker, that he looked forward to “a second revolution when the country will stop smoking at the dinner table.”

What drew Havel to the Dalai Lama was his desire for spirituality, and many agree that he was fascinated by him on a human level. But it was also Havel the politician who felt the need to support the Dalai Lama in his legitimate efforts to preserve Tibetan autonomy against Chinese Communist oppression. Even as a president and statesman, he did not change his priorities and was actively concerned about human rights everywhere, so that his attitude toward Tibet and the presence of the Dalai Lama were a logical outcome of that attitude.

As soon as the plane touched down, sympathizers gathered at the airport with improvised banners welcoming the “exotic visitor.” Video footage shows His Holiness’ beaming face as he steps off the plane and sets foot for the first time in his life on the soil of a former Communist bloc country (apart from a brief visit to East Berlin on his way to receive the Nobel Prize).

The Dalai Lama’s visit seemed to be telling the people of Czechoslovakia and the whole world: This is the new us, these are the values we profess; Communism is gone and will never return. We stand for the oppressed elsewhere in the world; Tibet has our support, it too deserves its freedom.

The Chinese embassy protested, but nobody was too worried about it. As president of a now-free country, Havel, who had always been guided less by interests than by principles, had simply extended an invitation to the Tibetan leader.

The Dalai Lama’s first visit to Prague was a political and cultural milestone for hosts and visitors alike. For the Czechoslovaks, the arrival of the Tibetan leader marked one of the new regime’s first significant acts of foreign policy, a clear symbol of the rejection of the old order in the newly liberated country. For the Tibetans, they were able to see their spiritual and political leader walking side by side with one of the most important representatives of the democratic movement in the world. This gave them great hope that they too would one day rid themselves of authoritarian rule in a similar fashion. Since then, the Dalai Lama has visited the Czech Republic 10 times—twice since the death of Václav Havel—as a participant in conferences and ecumenical meetings within the framework of FORUM 2000.

The Dalai Lama had traveled abroad prior to his first visit to Prague, but not nearly as much as after his meeting with Václav Havel. He toured Europe in 1973 and at the end of that decade he visited the United States for the first time, including Congress, and around the same time he also addressed the European Parliament. The Nobel Prize has contributed to his prestige and his universal renown, and fostered the interest of the world public in the Tibetan issue. However, it may be said that Václav Havel was the one who, with his unexpected invitation, really broke a longstanding taboo, because until then no head of state had honored the Dalai Lama in such a way.

The voice of Czechoslovakia in the World

If people in the world knew about Czechoslovakia, it was mainly thanks to Václav Havel. He quickly became a globally recognized moral icon and authority, and not only politicians but people from all walks of life, including business and show business, not to mention rock stars like the Rolling Stones, were interested in meeting him. What Havel did or said attracted unprecedented media interest, and choosing to meet the Dalai Lama worked like a spell, opening other important doors, from the White House to the Élysée Palace and the Bundestag.

That there was something mystical in Václav Havel’s relationship with the Dalai Lama is confirmed by their last meeting. In the summer of 2011, Havel’s health deteriorated, and the Dalai Lama was informed of the fact. That October, Václav Havel celebrated his 75th birthday, but he gradually withdrew from public life. In November, Czech television broadcast his last ever public interview—with his former cellmate who had deepened his relationship with faith and spirituality while in prison, the current Cardinal Dominik Duka.

On Saturday, Dec. 10, 2011, again symbolically on Human Rights Day and on the anniversary of the awarding of the Nobel Prize to the Dalai Lama, the two men met for what we now know was the last time. The two of them first spent some time alone and then made a joint appearance before the press. Václav Havel was visibly frail and obviously very ill, but he was smiling and pleased to meet his precious friend. A week later, on Dec. 18, Václav Havel breathed his last and, as described by Sister Boromejka, the nun who cared for him in his last moments, it was as if he had blown out a candle. The flame of a fulfilled life had gone out, and His Holiness the Dalai Lama was the last guest and friend to say goodbye to him in person just before his death. In a way, it was otherworldly and completed the circle.

The Dalai Lama has returned to Prague twice since Havel’s death. Each time he stressed how strong their relationship was, but most importantly he appealed to us to carry on fulfilling Havel’s legacy. What the Dalai Lama has in mind are Havel’s universal principles and moral fortitude, his lifelong concern for human rights and the environment, and his belief in the meaningfulness of dialogue and bringing nations together, as is happening, for example, in the European Union, which received the strong support of both Havel and the Dalai Lama.

But we should also feel a commitment because of Havel’s attitude to Tibet, a country to which he offered moral support uncompromisingly from the time he took office until the end of his life. He remained firm in his view that human rights take precedence over economic interests. Once, while still in office, he wrote to His Holiness that if the Beijing government ever invited him to China, he would insist on visiting Tibet and Taiwan as part of the trip. Needless to say, the Chinese never invited him.

On the occasion of the important 4th International Meeting of Tibet Support Groups hosted by the Czech Senate in 2003, Havel gave a speech that clearly illustrates his retrospective view of the decision he had taken over a decade earlier and that shows that he stood by it and would not act differently in the future:

“When in 1990, at the very beginning of my first presidential term, I welcomed the supreme spiritual leader of the Tibetan nation to Prague, I caused some confusion; allegedly the invitation to His Holiness was due to my lack of political and diplomatic experience. To risk worsening relations between Czechoslovakia and mighty China seemed to many to be an act of sheer recklessness. Since then, however, His Holiness has visited our country several times and Beijing has not yet declared war on us.

“However, we keep hearing that we should not interfere in matters that are none of our business, that we do not understand the problem at all and that the Czech Republic and Tibet have nothing in common. This is the same attitude for which the Czech nation has already paid dearly for the loss of freedom on more than one occasion. Will we never learn? Unlike some of my critics, I believe that if the Czech Republic was unable to export some of its goods to China, it would only be because we have been overtaken by our competitors, not because of our friendly relations with the government-in-exile in Tibet or because we put respect for human rights ahead of momentary commercial interests.

“Why should the greatest power in Asia be afraid of His Holiness the Dalai Lama, who commands no troops? I can personally testify (although it never ceases to fascinate me) that autocratic politicians, backed by the entire state apparatus, including the military, are always annoyed when someone stands up to them, even though that person is armed with nothing more than a belief in truth and non-violence.

“I am convinced that the desire for freedom is one of the fundamental traits of human nature. No politician in the world can ignore this fact. The struggle for freedom by non-violent means may be temporarily halted, but never destroyed.”

Not to fear meeting

The politicians who have succeeded Havel in the Czech Republic and elsewhere have not been so principled. This has also contributed to the current situation in which China has unprecedented influence and, with the help of state-of-the-art technology, is undermining and subverting Western democratic countries and their values, as well as manipulating the media and practicing censorship at home, while seeking to exercise it abroad.

The current geopolitical situation seems to be extremely complex, and world politics is once again lapsing into the taboos of the pre-Havel era, when meeting the Dalai Lama was something unacceptable, something that top leaders were reluctant to do for reasons of so-called realpolitik, lest they provoke some kind of imaginary retaliation from China.

We must ask ourselves why liberal democracies are succumbing so readily to this pressure and abandoning their own values and principles in the name of so-called economic interests. Let us ask ourselves what would happen if the entire free world were to say at the same moment a clear “no” to Chinese intimidation and blackmail. What would happen if Western leaders were to say to China with one voice that they stood behind Tibet and the Dalai Lama, that they stood behind the right of the people to freedom of religion and the development of their own culture. That, like Havel, they placed human dignity and human rights above narrow utilitarian interests and behaved in a way that was right. The answer is banally simple: “nothing” would happen at all. China would not stop doing business with the world, its threats would be empty saber-rattling with no real impact.

If the world will be commemorating the outstanding figure of Václav Havel on the 10th anniversary of his death, and if statesmen will be lauding with due emotion his merits and the ideas he promoted, it might be a good idea for them to examine their consciences and emulate Havel with practical actions.

They should send a clear signal to China that they will not be intimidated or blackmailed, that they will meet with whomever they want, whether it be Tibetan emigrants or Uyghurs, that they will support dissidents and prisoners of conscience in China, the way that Havel stood up publicly and with complete commitment for the signatories of the 2008 “Charter 08,” inspired by the Czechoslovak “Charter 77.” The best-known of them, Liu Xiaobo, who lost first his freedom and then his life as a result of the Communist regime, was not allowed to personally accept the Nobel Peace Prize, which he was awarded shortly before his death. It was precisely for him that Havel drew up a petition calling for his release from prison, which he personally placed in the mailbox of the Chinese Embassy in Prague in 2008, in the presence of the media.

Photo: Ondrej Besperat.

We can all follow the advice of His Holiness the Dalai Lama and fulfil the legacy of Václav Havel: by being truthful, by seeing environmental and climate protection issues as absolutely fundamental, by supporting and protecting the European Union, and by not forgetting Tibet and its people. Because, as Václav Havel wrote: if human freedom is denied to anyone in the world, it is therefore denied, indirectly, to all people. Long live Havel, long live the Dalai Lama!

Katerina Bursik Jaques served as Head of the Human Rights Department in the Government of the Czech Republic. She was also Director of the Office of the Deputy Prime Minister and the Government Commissioner for Human Rights. She is a former Member of the Parliament of the Czech Republic, Chairperson of the Parliamentary Committee on European Affairs and a Member of the Foreign Affairs Committee. She founded and chaired the Tibet Support Group in the Czech Parliament and organized His Holiness the Dalai Lama’s official visit in the Parliament of the Czech Republic. Katerina is Co-founder of the NGO “Czechs Support Tibet.” She is a member of ICT Germany, Secretary of the Tibet Support Group in the Czech Parliament and Member of the Steering Committee of the International Tibet Network.