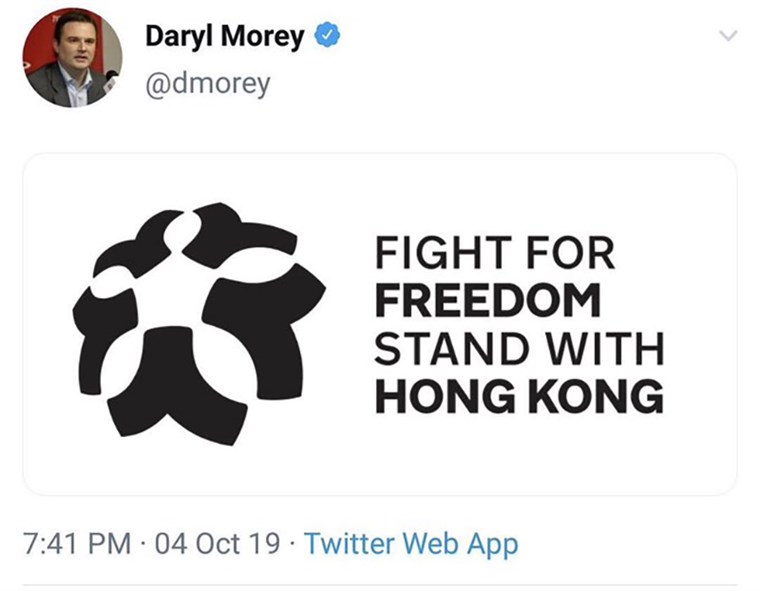

The scandalous—and quickly deleted—tweet in which Houston Rockets General Manager Daryl Morey showed support for Hong Kong protestors.

In case you haven’t heard, a public relations catastrophe has erupted in the National Basketball Association since Daryl Morey, general manager of the Houston Rockets, tweeted an image late last week captioned “Fight For Freedom. Stand With Hong Kong.” Morey later deleted the tweet and apologized, but that didn’t spare him or the league from China’s predictable wrath.

The Chinese consulate in Houston proclaimed it was “deeply shocked” by Morey’s “erroneous comments” and urged the Rockets to “take immediate concrete measures” to repair the damage. The Chinese Basketball Association suspended cooperation with the Rockets (which was particularly stinging, since the association is led by Chinese basketball legend Yao Ming, who spent his entire NBA career in Houston). Some Chinese businesses also ended their sponsorship deals with the Rockets.

Chinese entities also took revenge on the NBA itself, in part because of the league’s qualified response to Morey’s tweet. State broadcaster CCTV declared it would no longer air two NBA preseason games that were scheduled to be played in China; CCTV also said it was reviewing its cooperation with the NBA in toto. And on Wednesday, a press event in Shanghai with LeBron James, the greatest NBA player of this generation, was cancelled just hours before it was slated to begin.

Morey marooned by NBA peers

While this histrionic response from China was no surprise to anyone who monitors the country, the reaction of the NBA community has been far more troubling. It’s important to note that Morey, who helped revolutionize the NBA through his use of analytics, is often considered one of the best general managers in the league and was already a household name among basketball fans. But because he provoked China, his team allegedly considered firing him. The team’s owner, Tilman Fertitta, tweeted that Morey “does NOT speak” for the Rockets and that the Rockets “are NOT a political organization”—as if Hong Kongers’ fight for their basic freedoms were tantamount to voting for the local school board.

Another badge of shame goes to Rockets star James Harden, the 2018 NBA Most Valuable Player award winner, who responded to his general manager’s tweet by saying, “We apologize. You know, we love China.” In the past, Harden has rightly spoken up about racial injustice in the US. But when it comes to justice for Hong Kong, he is apparently willing to look the other way.

Perhaps most eye-roll-inducing was the “Open letter to all NBA fans” from Joe Tsai, owner of the Brooklyn Nets and executive vice chairman of the Alibaba Group, one of China’s most powerful companies. In his lengthy screed, Tsai writes that “1.4 billion Chinese citizens stand united when it comes to the territorial integrity of China and the country’s sovereignty over her homeland. This issue is non-negotiable.” I would like to tell Tsai that earlier this month, I attended an event on Capitol Hill led by Chinese dissidents who decried the 70th anniversary of Communist Party rule in their homeland; does Tsai believe he also speaks for them? In addition, the protestors in Hong Kong are Chinese people who appear to have a different take on national sovereignty than Tsai does. (If only the wealthy could realize that being rich doesn’t qualify them to act as spokespeople for the unwashed masses.)

To his credit, NBA Commissioner Adam Silver—after a confusing initial statement that any communications professional would recognize as the stitched-together work of multiple PR flaks—said the league would protect its employees’ freedom of speech and would live with the consequences of Morey’s tweet. However, Silver’s qualified response stands in contrast to the decisive action he took when he led the ouster of former Los Angeles Clippers owner Donald Sterling, who was caught on tape making repulsive, racist remarks.

Today Hong Kong, yesterday Tibet

Tibet supporters have seen this script before. In recent years, several Western businesses have prostrated themselves before China after invoking Tibet and Tibetans in ways that displeased the Communist Party.

Last year, Marriott President Arne Sorenson issued a statement saying “we don’t support anyone who subverts the sovereignty and territorial integrity of China.” That came after China shut down the hotel chain’s Chinese website as punishment for listing Tibet, along with Hong Kong, Macau and Taiwan, as separate countries from China. The International Campaign for Tibet (ICT) responded to Sorenson with a letter seeking clarification of his views on Tibetan human rights.

Most egregiously of all, Marriott then fired a US employee in Nebraska who accidentally liked a pro-Tibet tweet from a company account. As Sen. Marco Rubio (R-Fla.) said at the time, “This is the long arm of China. They can get an ‘American’ company to fire an American worker in America.”

Also in 2018, Mercedes-Benz apologized for quoting the Dalai Lama in an Instagram post. The quote itself—“Look at situations from all angles, and you will become more open”—was not overtly political, but the German carmaker disowned the post as an “extremely erroneous message.” As ICT Germany Executive Director Kai Müller said at the time, “Mercedes-Benz not only adapts to the language rules of the Chinese Communist Party, but even pledges to support Beijing in its worldwide effort to export its censorship.”

The film industry has also fallen under China’s sway. In December of last year, I wrote a blog post exploring how, after the 1997 twin releases of “Seven Years in Tibet” and “Kundun,” Beijing has been able to cut Tibet almost entirely out of Hollywood films. One galling example was how Disney changed the character of the Ancient One in “Doctor Strange” from a Tibetan in the original comic books to a Celt played by Tilda Swinton in the movie version, cynically claiming its goal was to avoid racial stereotyping. However, the screenwriter of “Doctor Strange” admitted that, “If you acknowledge that Tibet is a place and that [the character is] Tibetan, you risk alienating 1 billion people.”

In my post, I pointed out that it is not just businesses that are adhering to Chinese views on Tibet. According to the 2018 annual report of the US-China Economic and Security Review Commission, European diplomats choose not to discuss Tibet because they don’t want to face Beijing’s wrath.

As I wrote, “The result is arguably the most insidious form of censorship: self-censorship. And it’s becoming more common on the issue of Tibet.”

Taking a page from Orwell

To understand how self-censorship works, we can look to George Orwell’s “Animal Farm”—not the main narrative itself, but rather the stunning preface that Orwell wrote.

“Animal Farm” is, of course, a thinly-veiled allegory about the Soviet Union, the West’s great adversary during the Cold War. So it is a bit surprising to read in the preface just how difficult it was for Orwell to get British and American publishers to accept the book. At the time, the Soviets were allies of the UK and US in the war against Nazi Germany. That made Orwell’s anti-Stalinist drama simply unpalatable.

What’s most shocking is that the British government never outright banned publishers from printing Orwell’s book. Instead, publishers simply felt it “wouldn’t do” to distribute the book in light of Britain’s alliance with the Soviets. One publisher even voluntarily ran the book past the UK’s ministry of information. That publisher later wrote to Orwell that “the choice of pigs” to represent Soviet leaders “will no doubt give offence to many people, and particularly to anyone who is a bit touchy, as undoubtedly the Russians are.”

Substitute “Chinese” for Russians, and swap out pigs that mock Stalin with tweets that support Hong Kongers or Tibetans or Uyghurs, and you basically have the situation we’re in today.

Resist Chinese censorship

Though Orwell is recognized as one of the most acute critics of totalitarian societies, such as China, his preface to “Animal Farm” is invaluable for understanding how censorship is imposed on supposedly free societies such as ours. In place of government restrictions, private entities like the Houston Rockets, Marriott and Mercedes act as consenting enforcers of Chinese thought proscription. That’s how an action as mild as Daryl Morey tweeting could incite such a firestorm.

The actual substance of his tweet—fight for democracy and freedom, stand with those who are doing so—is so unremarkable that it’s hard to imagine many Americans disagreeing with it. But because the tweet agitated the people in charge of one of the most important business partners for the NBA, Morey was hung out to dry. (Thankfully, while US businesses have demonstrated time and again that they can’t be trusted on the issue of China, US lawmakers on both sides of the aisle continue to stand up to Chinese attacks on our free speech.)

In the long run, the Pandora’s Box that Morey’s tweet seems to have opened may come back to bite China, because the American public is now much more aware of how the Chinese Communist Party impedes their ability to speak freely. It’s one thing for China to strong-arm a car company or hotel chain; it’s quite another to mess with the highly visible and opinionated arena of sports fandom. (It also helps that “South Park” just aired an episode mocking Chinese censorship, followed by a sarcastic ‘apology’ to China from the show’s creators.)

Americans should be terrified by the way Chinese censorship has taken hold in our public life and determined to prevent it from going any further. Let this moment be a turning point where all of us speak out against the deep reach of Chinese free speech curtailment in the US and refuse to be quiet about our support for Hong Kongers, Uyghurs, Chinese dissidents and Tibetans.