Years ago, at a different job, a coworker asked if I had always been a contrarian. The question struck me like an apple falling from a tree. I had never seen myself as a contrarian, but perhaps that one word could explain why as a young man I so often felt at odds with the world.

Years ago, at a different job, a coworker asked if I had always been a contrarian. The question struck me like an apple falling from a tree. I had never seen myself as a contrarian, but perhaps that one word could explain why as a young man I so often felt at odds with the world.

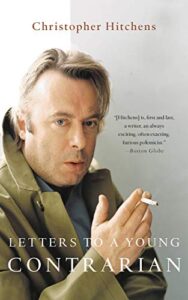

Invigorated by the potential for self-understanding, I went to Barnes & Noble and began reading Christopher Hitchens’ “Letters to a Young Contrarian.” The book, Hitchens writes in the first chapter, is addressed to those who feel “a disposition to resistance, however slight, against arbitrary authority or witless mass opinion, or a thrill of recognition when you encounter some well-wrought phrase from a free intelligence.” My ego was tickled.

But a few pages later, I encountered a splash of iconoclasm that stopped me in my tracks. After assailing anti-Semites and racists and the atom-bombing of Japan, Hitchens shifts his aim to a very different target: the Dalai Lama. Quoting a speech in which the Tibetan leader relates his belief that we are all seeking happiness, Hitchens sneers: “The very best that can be said is that he uttered a string of fatuous non sequiturs.”

“[H]uman beings do not, in fact, desire to live in some Disneyland of the mind, where there is an end to striving and a general feeling of contentment and bliss,” Hitchens writes, adding: “Even if we did really harbor this desire, it would fortunately be unattainable.”

Suddenly, I was off the contrarian train almost as quickly as I’d hopped on.

Spared by the Dalai Lama

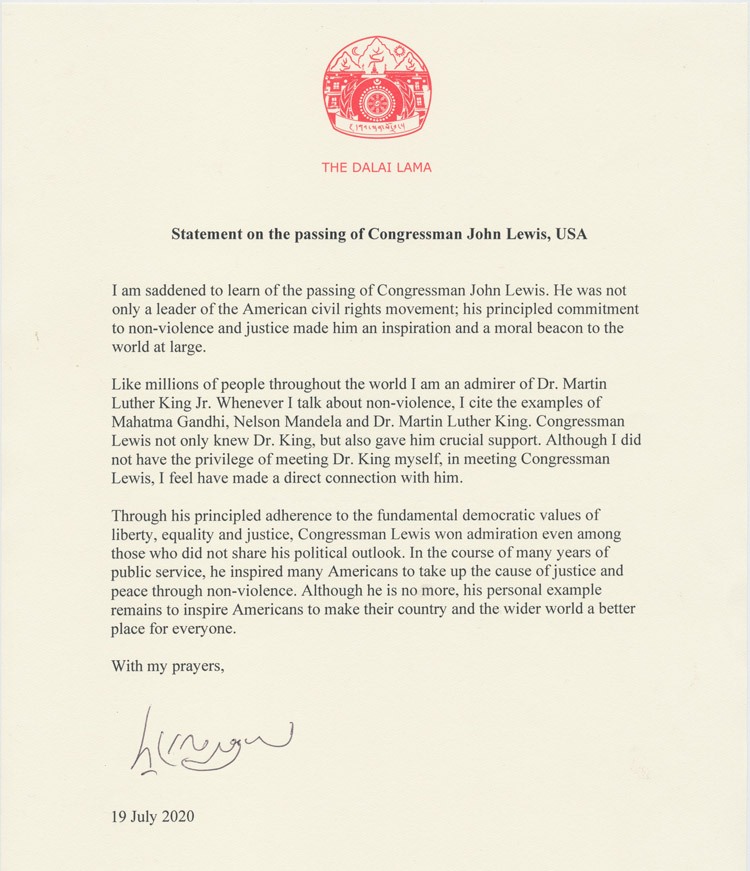

It turned out “Letters to a Young Contrarian” was not the only time Hitchens, who died in 2011, sicced his estimable wit on the Dalai Lama. In a piece for Salon in 1998, he dismisses His Holiness as a “[creature] of the material world.” Elsewhere, he maligns the Dalai Lama for claiming to be a “hereditary king appointed by heaven itself” and enforcing “one-man rule” in his exile home of Dharamsala (more on that later).

I, for one, don’t believe anyone is beyond reproach. Good-faith criticism can be made of the Dalai Lama—his words and actions, as well as his status and followers.

As one of those followers, I hold myself up for critique—though my behavior shouldn’t reflect on anyone else—in part because I see how far short I fall of His Holiness. I can’t deny I’m prone to pessimism and hand-wringing; I tend to be doubtful of attempts to improve the world while simultaneously mournful over the state of it. (I’m also too self-critical, if you haven’t noticed.)

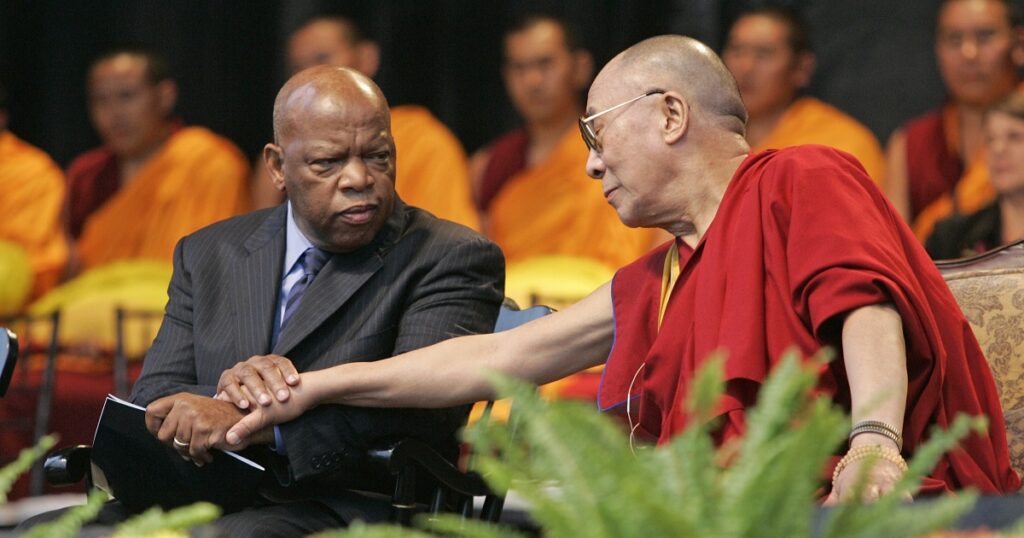

And yet, even before I joined ICT, I never felt the need to doubt His Holiness. In fact, the Dalai Lama and figures like him—Gandhi and John Lewis come to mind—have helped spare me from a life of total cynicism. If it weren’t for them, I might not believe in anything. That’s not because I think they’re unimpeachable. It’s not even, for me, whether they achieved their overall goals or not.

Instead, the mere fact that a person like His Holiness exists in this world helps sustain my faith in humanity. From his humble living quarters to his transcendent wisdom to his innumerable displays of kindness—let alone his remarkable ability to forgive and seek reconciliation with his Chinese antagonists—His Holiness lives much the way you’d want everyone to live.

Who could ever be cynical about that?

Contrary to facts

It seems Hitchens was motivated to ‘take down’ His Holiness not just because Hitchens was an anti-theist and a libertine, but because His Holiness is a popular leader around the globe. The public generally loves the Dalai Lama, so Hitchens, driven by a need to look down on the herd, felt compelled to diminish its “witless mass opinion.” I can’t say that for certain, but it’s the impression I get reading Hitchens’ work and knowing other people like him.

There’s no denying Hitchens’ eloquence, and often, he trained his sights on deserving victims, especially politicians and people in government. But one of the problems with contrarianism—with preferring to disagree and express unpopular views—is that it prevents you from seeing things as they truly are (the same can be said of partisanship). Hitchens’ Salon piece, for instance, relies more on breezy suppositions and tendentiousness than on objective reporting.

Although Hitchens disdained religion, he was just as zealous as some fundamentalists in overlooking facts that got in the way of his faith. Take his claim about the Dalai Lama’s “one-man rule” in Dharamsala. That is simply, demonstrably false; ask the democratically elected Indian and Tibetan governments in the city if you have any doubt.

Hitchens’ assertion that His Holiness claims to be a “hereditary king appointed by heaven itself” is also easily refuted by the evidence. As Andrew Goodwin writes in Tricycle, the Dalai Lama

“has said, repeatedly and in plain language, that he is not a special person or a supernatural being, but an ordinary man. The second point of significance is his comment that if science proved Buddhist teachings incorrect in any way, then Buddhism would have to change. One might have expected that a book written by a well-informed journalist [Hitchens] who is appalled at the irrationality of religion would have found space to mention this.”

Hitchens is famous, among other things, for “Hitchens’s razor,” the belief that “what can be asserted without evidence can also be dismissed without evidence.” Heaven forbid his razor should be applied to his own writing on the Dalai Lama.

Rebels without a cause

I’ve spent a lot of time talking about Hitchens, who has been dead for over a decade. But unfortunately, his vapid views on the Dalai Lama have found voice in some contrarians of today.

Take, for example, media personality Max Blumenthal, who is almost comical in his contrarianism. Blumenthal doesn’t just criticize the US government—which is totally fair and appropriate, as I argue below—he actively defends the governments of Russia, Syria and, yes, China. In fact, he has appeared several times in Chinese state media to dispute accusations of atrocities by Beijing, including the claim of genocide against Uyghurs.

In a 2019 article in MintPress News, Blumenthal ahistorically describes the Dalai Lama as “the head of a relatively minor Buddhist sect until it was exploited by the CIA as a weapon against communist China.” He also asserts that “Tibetan Buddhists seek a return to theocratic feudal rule in the [Tibetan] plateau.”

That might be news to Tibetans in exile, who had a voter turnout of over 70% in 2021 when they elected Penpa Tsering the Sikyong (President) of the Central Tibetan Administration, the position to which His Holiness devolved political power in 2011 in line with his belief in the separation of church and state. Before China forced him into exile in 1959, the Dalai Lama even tried social and land reforms inside Tibet, but the Chinese blocked his efforts. It seems the Tibetan Buddhist leader does not seek theocracy or feudalism after all. (One gets the impression Blumenthal has never actually spoken to a Tibetan Buddhist in his life.)

Blumenthal is founder and editor of The Grayzone, a news website that’s also home to Aaron Maté, a fellow Chinese state media contributor and the son of world-famous doctor Gabor Maté. Blumenthal, for his part, is the son of a former senior advisor to President Bill Clinton, and he graduated from Georgetown Day School in Washington before matriculating to the Ivy League.

I don’t know Blumenthal or Maté or their motives, but it’s not surprising to me that two of the most aggressive apologists for China in US media are wealthy, White—Blumenthal’s claim about Tibetan Buddhists seeking feudal theocracy is racist and colonialist—children of famous parents. Part of contrarianism is rebellion, and these two sons of privilege fit the part of rebels without a cause.

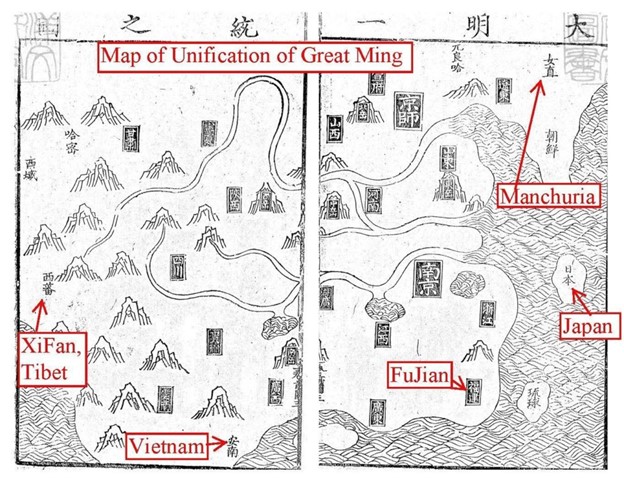

Rewriting history

Sadly, a parade of contrarians, useful idiots and CCP shills have come out in full force recently in the wake of a misleading video clip showing His Holiness with a young boy in India. The video clip understandably provoked controversy and a flood of news coverage, and the Dalai Lama’s office quickly responded with an apology on his behalf.

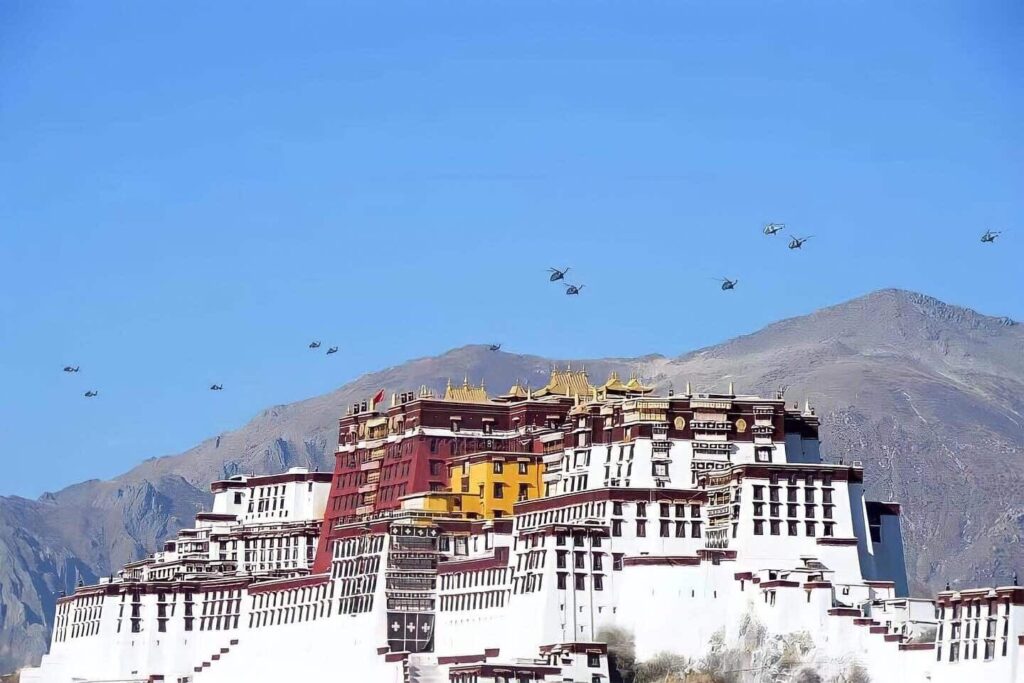

As I write above, good-faith criticism of His Holiness is fine. But several commentators have sickly exploited this incident to rewrite history and justify China’s brutal occupation of Tibet. For some, that’s likely because it serves their brand to do so. But others seem to have genuinely let their critique of the United States blind them into drinking China’s Kool-Aid.

Indeed, long before the current headlines, I saw several self-proclaimed progressives write off Tibet as a vehicle for America’s foreign interference and imperialism, conveniently ignoring that China’s rule in Tibet is imperial. (In fact, it seems quite likely China lackeys helped engineer this recent controversy by purposefully spreading an out-of-context clip from over one month ago to manipulate the news cycle and discredit one of Beijing’s oldest foes without concern for the effect this would have on the young child.)

Don’t be a dum dum

No one can deny our leaders in the US have done horrible things and lied about them. Many institutions in this country—from government to media to banks to schools to houses of worship—have betrayed the public trust, leaving people feeling powerless and atomized. In this environment, it’s easy to give in to a nihilistic urge to tear everything down or an ego-wish for moral superiority.

I get the allure, but it is a siren call. I’m reminded of a statement from the late YouTube host Michael Brooks, who tragically died three years ago. I never met Michael in person, but I did interact with him a couple times online, and he was kind enough to engage me on Twitter, perhaps out of solidarity with Tibetans and perhaps because of his long interest in Buddhism. (One of his video clips inspired my previous blog post about human rights.)

Brooks was a true man of the left, but in one of his most enduring segments, he called out what he termed “the dum dum left”:

There is, unfortunately still, a dum-dum left who confuse moral posturing with revolutionary fervor. Who confused ahistorical throwing anything at the wall and endless whining about the Democrats for a real radical stance towards politics … And I get why that’s emotionally appealing to people because we live in absolutely disgusting times and the governing class of this country and the globe is disgusting. It’s abusive, it’s cruel, it’s abusive, it’s stupid, it’s arrogant, it’s insular and they need to be mocked, ridiculed, debunked, and they need to be taken out, to keep it simple. But not too simple. We need to keep it as simple as it can be, but not simpler than that.”

Working toward a vision

It’s too simple to think: America bad, therefore China good. It’s too simple to believe the whole world is bad, so let’s just blow everything up. You have to have some positive, humane vision to work toward. In my opinion, His Holiness and Tibetan Buddhist culture provide that.

In my own case, I don’t think I ever truly was a contrarian, just someone with a perspective shaped by an immigrant, minority, lower-income background. I have no problem holding contrary views on sacred cows like Winston Churchill, for instance. I am still skeptical of mainstream politics and business, along with a litany of other things.

But I am not so skeptical that I can’t recognize a good person, however imperfect, when I see one. His Holiness the Dalai Lama is a good person, to say the least, and Tibet is a good cause. There are many things in this world worth taking down, but the Dalai Lama’s vision is worth building up.

Instead of contrarianism that leads to cheerleading the invasion of Iraq (like Hitchens) or parroting Chinese government propaganda (like Blumenthal, Maté and other online critics of Tibet), His Holiness offers a superior radicalism for today’s world. As the Dalai Lama says: “Compassion is the radicalism of our time.”