“It’s in keeping with the philosophy of nonviolence. That’s what the movement was always about, to have the capacity to forgive and move toward reconciliation.”—John Lewis

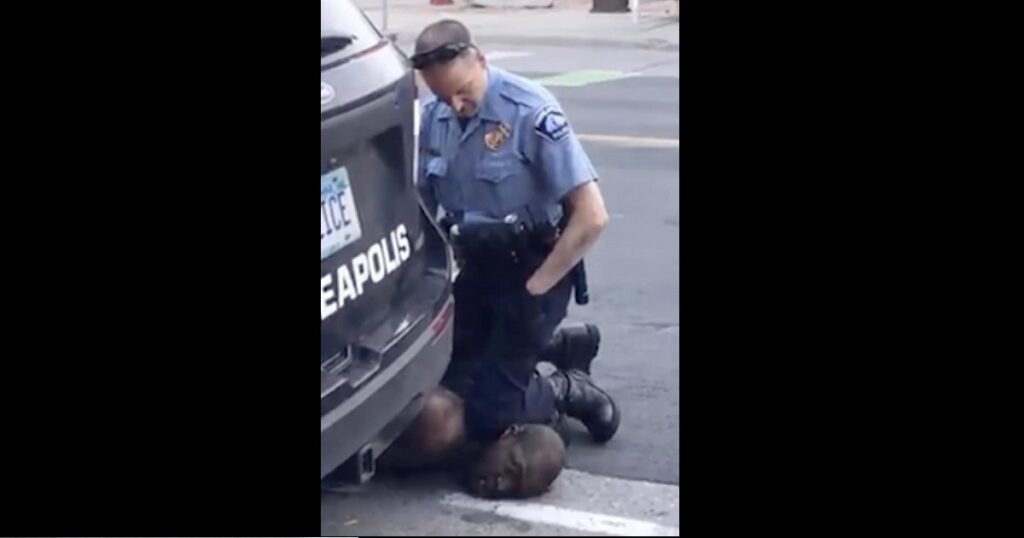

For obvious reasons, the timing of John Lewis’ death last week felt like a heavy blow. Not only have most of our lives ground to a halt in the wake of the coronavirus pandemic, but our country is also in the midst of a massive reckoning over racial injustice. And now we have lost the light of one of the last remaining luminaries of the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 60s. (The Rev. C.T. Vivian, another high-profile figure from the movement, died the same day as Lewis, July 17, 2020.)As a believer in the Dalai Lama’s nonviolent activism, I lament the passing of Congressman Lewis. I often fear that great moral leaders like Rep. Lewis, the Dalai Lama, Archbishop Desmond Tutu and their forebears are a rare species in our modern world, which—for whatever progress it has made—is also more fractured and imperiled than it ever has been in many of our lifetimes. The death of John Lewis only makes this frightening landscape feel a little dimmer.

Prayers from the Dalai Lama

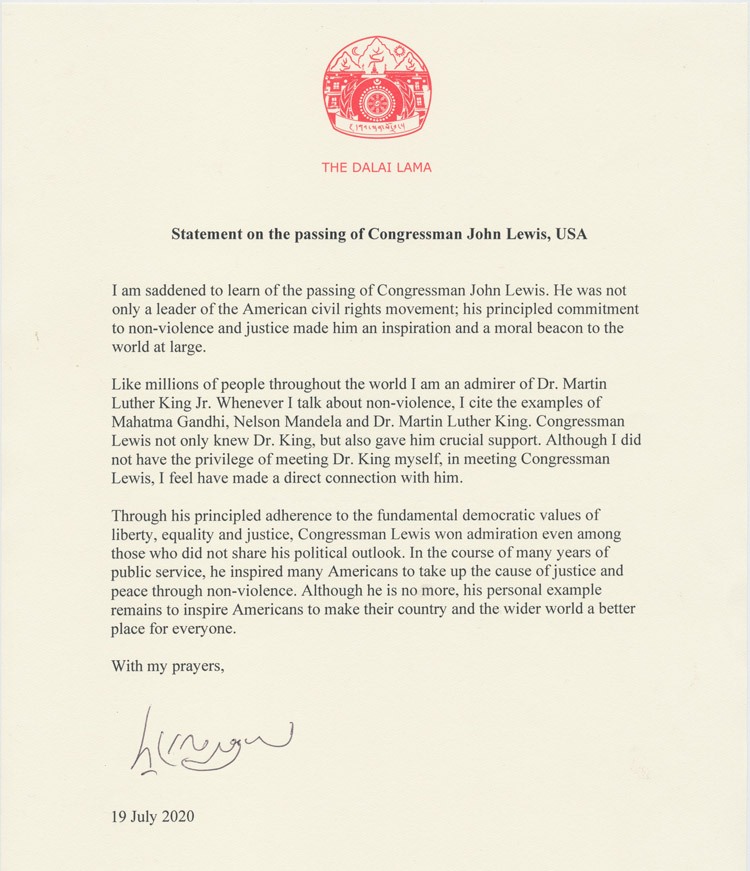

Given everything Lewis stood for (and got beaten for) during his lifetime, it’s no surprise the Dalai Lama mourned his death in a statement this past weekend. “Through his principled adherence to the fundamental democratic values of liberty, equality and justice, Congressman Lewis won admiration even among those who did not share his political outlook,” His Holiness wrote. “In the course of many years of public service, he inspired many Americans to take up the cause of justice and peace through nonviolence.”

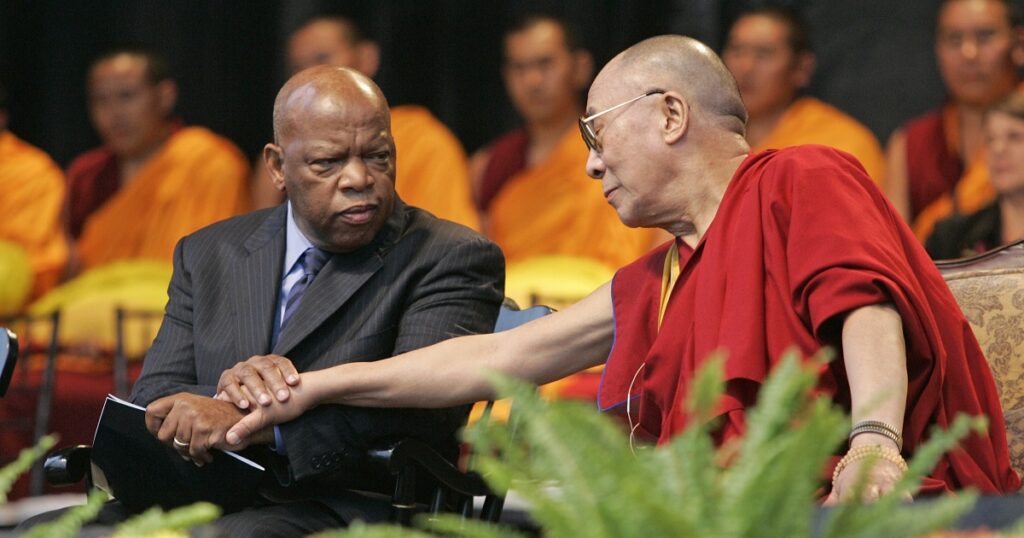

The Dalai Lama’s website also shared a photo of the Tibetan Buddhist leader clasping hands with Rep. Lewis—a striking image of two beaming avatars of wisdom and compassion. Lewis supported Tibet during his decades in Congress, including by signing onto several letters calling for greater US action to advance Tibetans’ rights.

In his statement, the Dalai Lama also connected Lewis to other icons of nonviolence:

Whenever I talk about nonviolence, I cite the examples of Mahatma Gandhi, Nelson Mandela and Dr. Martin Luther King. Congressman Lewis not only knew Dr. King, but also gave him crucial support. Although I did not have the privilege of meeting Dr. King myself, in meeting Congressman Lewis, I feel [I] have made a direct connection with him.

The power of forgiveness

I’ve written before on this blog about my admiration for Gandhi (as well as, of course, my love for His Holiness). But as an Indian immigrant in the US, I feel simultaneously proud that the civil rights movement borrowed methods and ideas from Gandhi’s “satyagraha” campaign and indebted to Black leaders like Congressman Lewis and Dr. King, who suffered horrific abuse—and even death in King’s case—so that people of color could have the same freedoms as their fellow citizens. I know the opportunities I’ve had in this country would not have been possible without those visionary activists, so I will forever be grateful.

Yet as inspired as I feel by how much Lewis, the son of Alabama sharecroppers, managed to achieve in his 80 years on this Earth, I am perhaps just as moved by how much he was willing to forgive.

As Michael A. Fletcher recalls in an excellent piece for The Undefeated, the beatific Lewis once faced criticism from his peers for having too much anger. At the legendary 1963 March on Washington where Dr. King delivered his famous “I Have a Dream” speech, the 23-year-old Lewis—who was one of the “Big Six” organizers of the event and the last one to die—had to tone down his remarks at the request of King, A. Philip Randolph and others, who feared the oration he planned to give was too divisive and combative.

Years later, Lewis fully embraced the need for forgiveness and reconciliation. According to Fletcher, he forgave “Bull” Connor, the notorious former public safety commissioner of Birmingham, Ala., who unleashed firehoses and attack dogs on peaceful protestors.

The capacity to change

Perhaps most strikingly of all, Lewis even forgave George Wallace, the man who famously pledged in his 1963 inauguration as Alabama governor, “segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever.”

Growing up decades after the fact, I knew Wallace only as a caricature of midcentury racism. What I did not learn until years later was that during the final stages of his life, Wallace—who by then was bound to a wheelchair following an attempt on his life—expressed remorse for the damage he caused African Americans. He met with Lewis in 1979 and with other civil rights leaders too.

Many people felt—and still feel—that Wallace’s about-face on racism was less than sincere. Yet in an astonishing op-ed he wrote for The New York Times the week Wallace died in 1998, Lewis said the Wallace he got to know “was a changed man.” “When I met George Wallace, I had to forgive him,” he wrote, “because to do otherwise — to hate him — would only perpetuate the evil system we sought to destroy.”

Lewis went on to say that Wallace “should be remembered for his capacity to change.” “I can never forget what George Wallace said and did as governor, as a national leader and as a political opportunist,” he wrote. “But our ability to forgive serves a higher moral purpose in our society.”

The effectiveness of nonviolence

Lewis was also willing to forgive less well-known figures too. In one of the most startling examples of his grace, he forgave Elwin Wilson, a Ku Klux Klan member who viciously beat Lewis and a fellow Freedom Rider at a bus station in the early 60s—Lewis and the other activist refused to fight back or press charges—before seeking him out to apologize and make amends decades later.

Lewis beautifully recalled their meeting about 10 years ago in Washington, DC: “He started crying, his son started crying, and I started crying,” he said. The quote from Lewis at the top of this post explains why he never hesitated to accept Wilson’s apology.

For his part, Wilson, who wanted to set things right with his God before it was too late, had wisdom of his own to dispense. “[M]y daddy always told me that a fool never changes his mind, and a smart man changes his mind,” he said. “And that’s what I’ve done and I’m not ashamed of it.” He and Lewis made several TV appearances together over the next few years, and when he died in 2013, Lewis issued a statement saying he was “very sorry to learn of Elwin Wilson’s passing.”

“He demonstrated the power of love and the effectiveness of nonviolent direct action,” Lewis said, “not only to fix legislative injustice but to mend the wounded souls in our society, the soul of the victim as well as the perpetrator.”

Hope for Tibet, hope for tomorrow

Though I’m sad that Congressman Lewis no longer walks this Earth with the rest of us, reading about him over the past few days has refocused my belief in the Tibetan cause and the vision of the Dalai Lama. Lewis’ success in changing the world, and changing individual people, renews my hope that change can come to Tibet.

I’m not saying it will be easy. Do I believe that Chen Quanguo, the architect of mass atrocities against Tibetans and Uyghurs, will undergo the same change of heart that Wallace and Wilson said they did? Not really, no. As Lewis himself noted in his op-ed, Wallace’s conversion was a rare feat for a politician.

Many of you probably also question whether it even matters to convert or forgive people like Wallace and Chen, given the immense harm they’ve caused. On top of that, even though I’ve followed the Dalai Lama and other nonviolent leaders for many years now, I’m still never sure how to put their teachings into practice—how to combat injustice and stand up for what’s right without becoming unjust or unkind myself.

I can also assure you that I have many of the same fears that many of you do about the coronavirus and its effect on our health, our economy, our future. There’s also the threat of climate change, the rise of authoritarianism and numerous other concerns to worry about.

Spirit of healing

Yet I know that whatever the next few months, as well as the next few years and decades, bring, I would prefer to face them with the spirit of compassion, nonviolence and healing that Lewis embodied, rather than with anger and vindictiveness.

That’s a big part of what drew me to Tibet in the first place, and I suspect it’s what drew many of you as well. It’s not about achieving victory over the Chinese, but about creating conditions for Tibetans and Chinese to live together peacefully, the way Lewis and his peers hoped different races in the US could live as equals.

Below is His Holiness’ full letter about the loss of Congressman Lewis. I hope you take a moment to read it, and I hope you stay committed to the cause of nonviolence and peace.

RIP JOHN LEWIS.