As the observed July 6 birthday of H.H. the Dalai Lama nears, his well-wishers throughout the world have already begun their own respective ways to organize events or launch initiatives to recall his impact on the community.

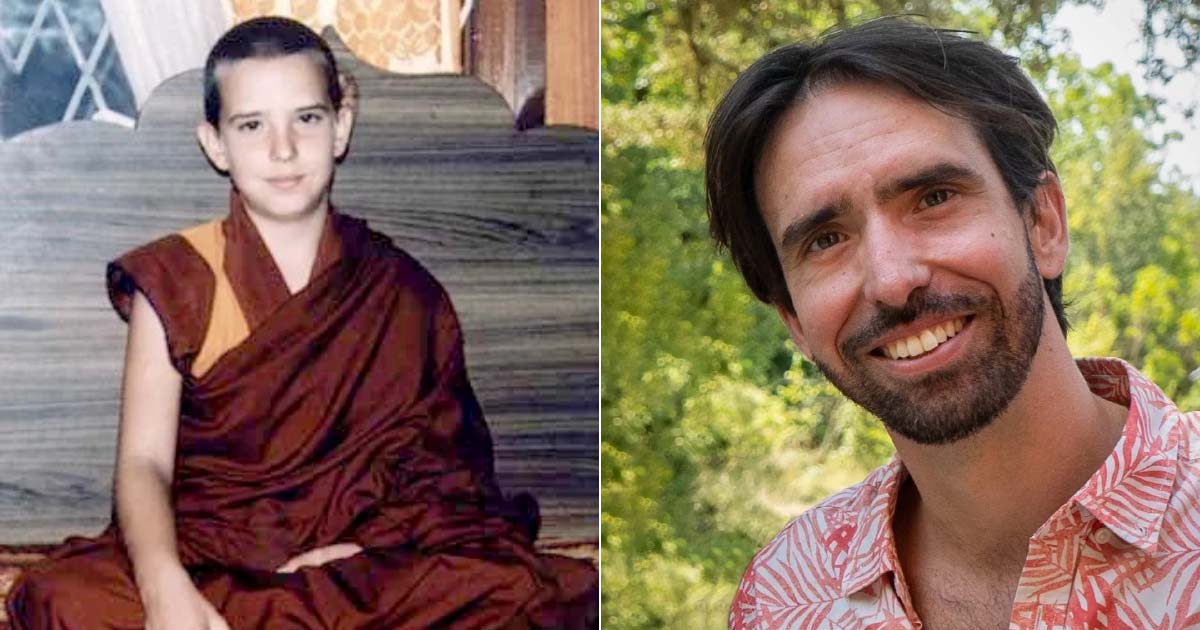

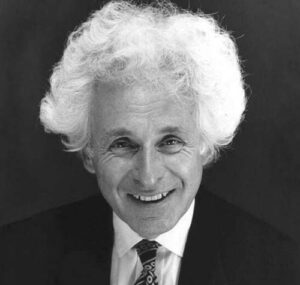

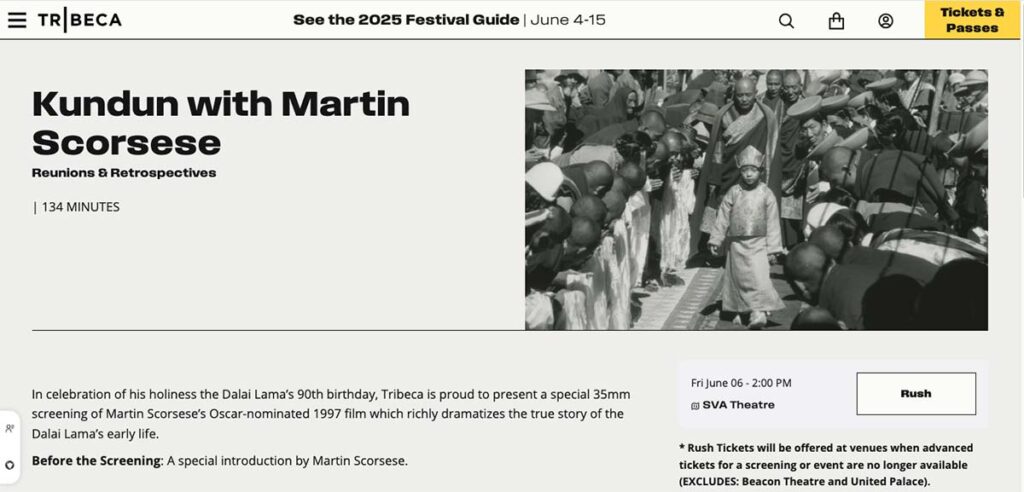

I wanted to dwell on three such initiatives today. June 6, 2025 saw the special screening of the iconic 1997 film “Kundun” at the Tribeca Film Festival in New York City, in partnership with the International Campaign for Tibet (ICT). What made the screening special was that Director Martin Scorsese was personally there to introduce the film and to put it in context. Scorsese mentioned the film’s strong spiritual impact on him and highlighted the message of oneness of humanity of the film, even in its production, saying that it is a story of a Buddhist, being made in an Islamic country (it was shot in Morocco), by a director who is “an Italian-American Roman Catholic from New York.” He mentioned how his film on “Supreme Holiness” as he reverently referred to the Dalai Lama was an effort “to embody His Holiness’ spiritual evolution”.

Scorsese’s remarks showed that his interest in Tibet was not just limited to the period of the production of Kundun (“I was always intrigued by Tibetan Buddhism”) and continues to be interested even after nearly three decades since its release. He mentioned being impressed by Tibetan cinema, by film makers like Pema Tseden (he mentioned ‘Old Dog’), Dzongsar Khyentse Rinpoche and Neten Chokling and wondered why “American distributors and streamers” were not considering a “Tibetan Film Festival” to showcase these talents. He seemed to indicate his interest in such a project saying, “So, let us get it going.” The presence of several cast members at the screening provided a humane touch to the audience in their appreciation of the film.

Jane Rosenthal of Tribeca Festival said the film showed “quiet strength to hold on to an identity in the face of erasure.” She said, “Kundun shows us that empathy begins with understanding and that there is no peace without compassion.” The screening was part of the Compassion Rising global campaign initiated by ICT on the 90th birthday year of H.H. the Dalai Lama.

The educational materials on Tibet and the Dalai Lama, including a specially-updated edition of his “A Human Approach to World Peace” (Wisdom Publications), that ICT distributed to the attendees of the screening provided context to the basis of his impact. That the message of the Dalai Lama continues to resonate with the American public could be gauged from fact that an overwhelming majority of the ticketed audience members for the screening were non-Tibetans. I am saying this because for a Tibetan to be attending the screening would just be a part of the natural expectation from a devotee.

Audience members waiting to enter the theatre for Kundun screening in New York.

Dalai Lama’s impact on the younger generation

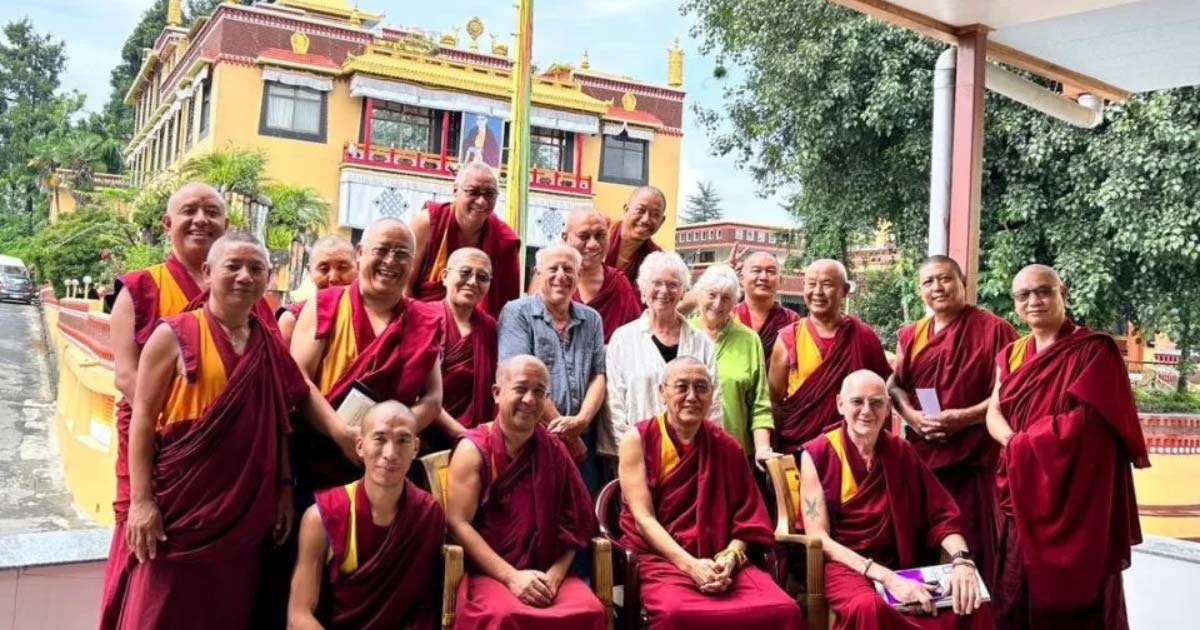

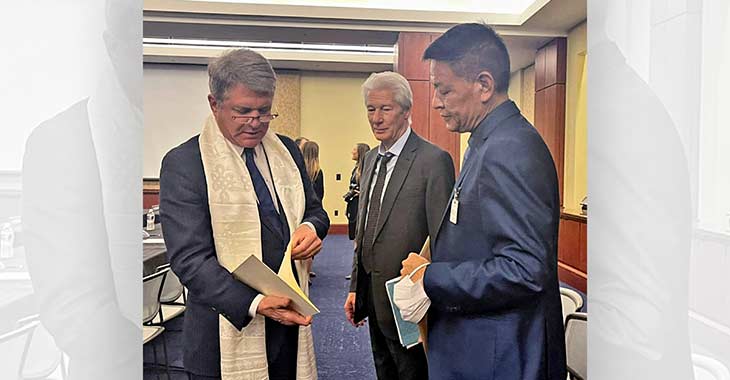

The second initiative was an event in Johns Hopkins University’s School of Advanced International Studies campus in Washington, D.C. on June 1, 2025. Organized by the Weekend Tibetan School of the Capital Area Tibetan Association in partnership with JHU, it was a focus on the Dalai Lama’s message of Love and Compassion. The half day event consisted of combination of presentations by young Tibetan American students on how the message of compassion was understood by them and how these impacted their individual lives. I was particularly impressed by the debate session on Love and Compassion among six students. Maybe it is due to my own lack of understanding of today’s youngsters, but I was very encouraged by the quality of responses (and the confidence with which they did so) by the students to the questions by the judges during the debate section. It does seem that the programs on Social Ethical and Emotional (SEE) Learning that they attended as part of their weekend school benefited their knowledge. Some of them mentioned how the knowledge enabled them to cope with the death of their pets or in dealing with an unpleasant fellow student. Even though some of the questions posed to them focused on the Tibetan community, interestingly the students’ responses were more about HH’s impact on the broader human community.

The six students who participated in the debate in Washington, DC on what compassion means to them.

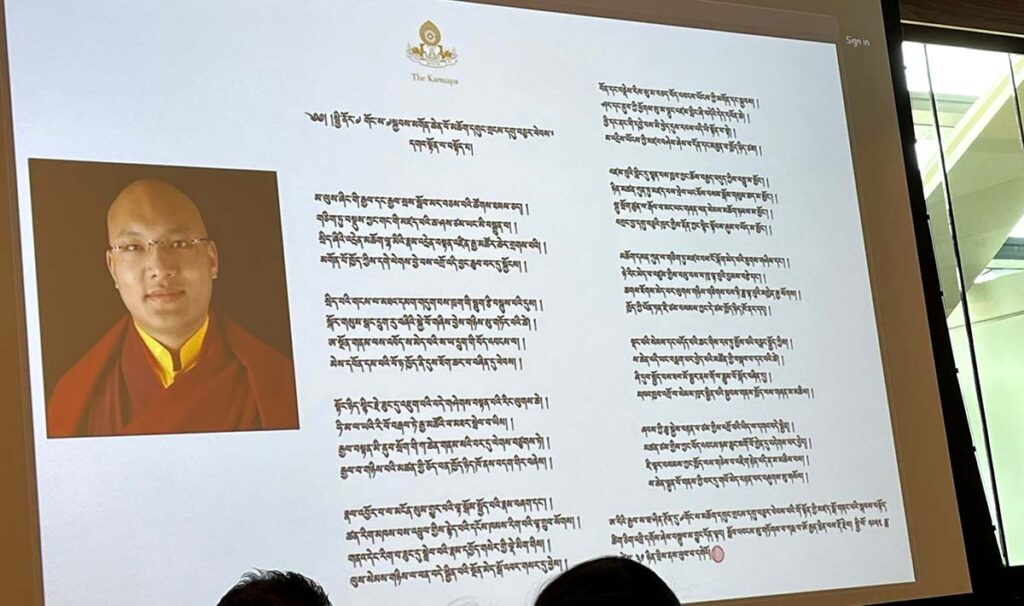

The adults who spoke at the event, both Tibetans and non-Tibetans, also put their own perspective on how HH’s message of compassion impacted them. A nine-stanza ode in Tibetan specially composed for the event by the Gyalwang Karmapa highlighting the Dalai Lama’s contribution was read.

Karmapa ode to the Dalai Lama displayed on the monitor at the venue.

Then there was a discussion on compassion by Tibetan Buddhist lamas and practitioner. This was followed by a medley of cultural dances performed with great gusto by the students, from young to comparatively older ones. It was a clear summation of the impact of the Dalai Lama’s message of compassion on the younger generation.

How the Dalai Lama shared his thoughts to the wider world

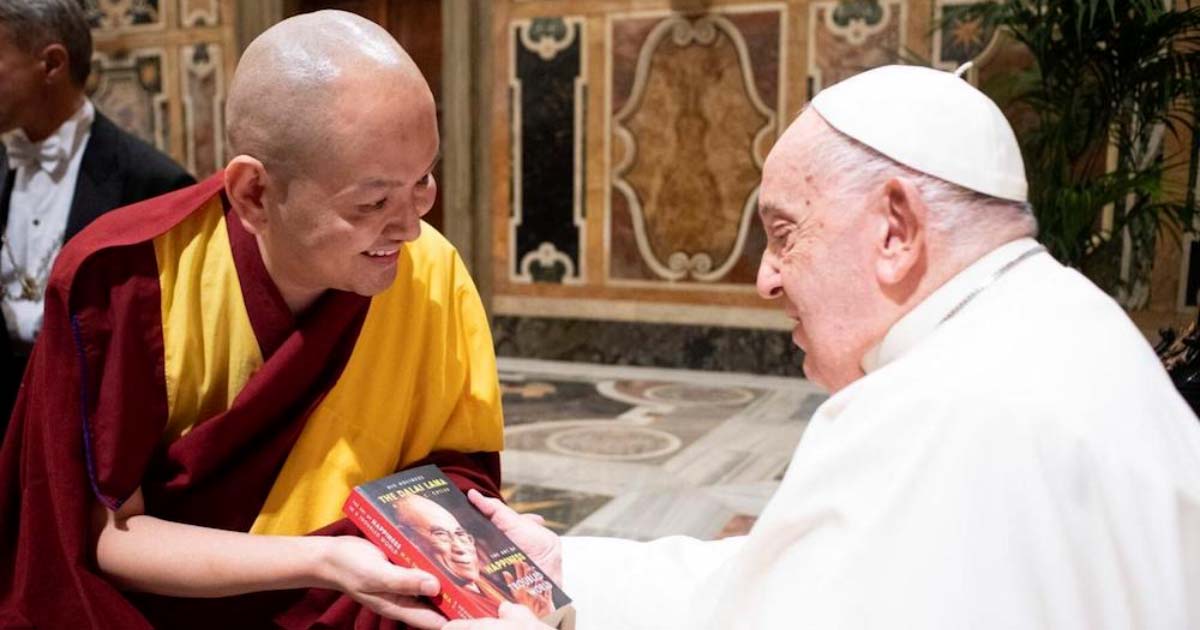

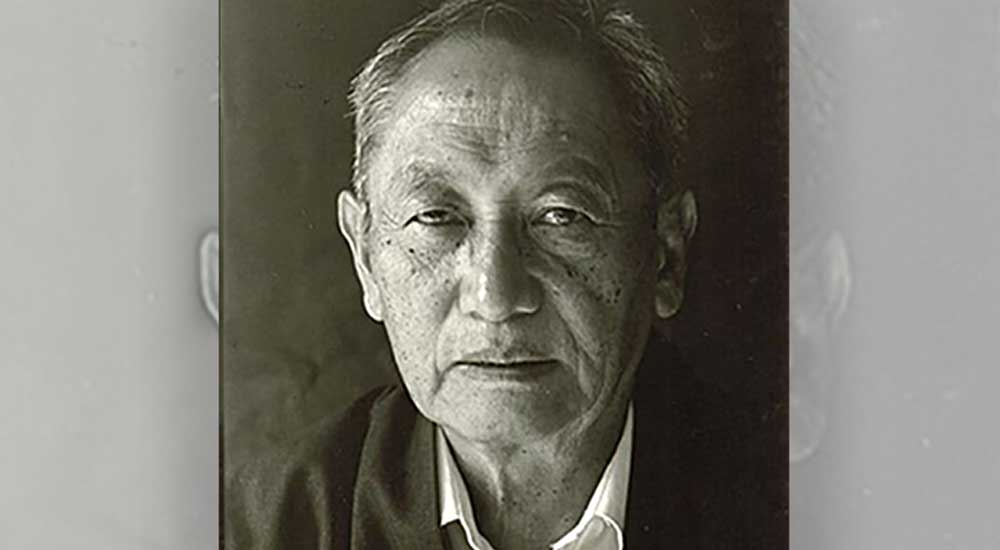

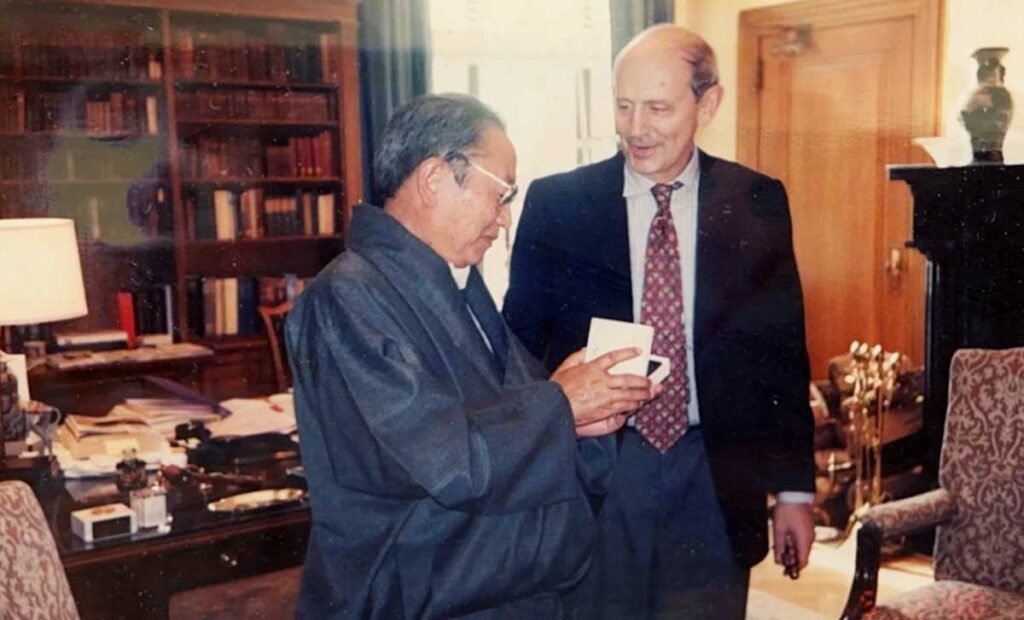

The third initiative was in the form of a book, Our Wish-fulling Gem Part 2: A Biography of His Holiness the Dalai Lama” (Library of Tibetan Works & Archives, Dharamsala, 2025), by educationist Chophel compiling the details on visits by His Holiness the Dalai Lama throughout the world outside of India from 2011 till 2018. Additionally, this second volume also has details on His Holiness’ visits within India from 2011 onwards. As in the first volume, in this book, too, the author provides an overview of His Holiness’ meetings and remarks at events big and small in different countries which are “a testament to the enduring influence of one of the world’s most revered spiritual figures.” His first volume, titled “Our Wish-Fulling Gem: A Biography of His Holiness the Dalai Lama” was published in 2022 and covered the first 75 years of His Holiness’ life. The author and I know each other, and I had the opportunity to read a drafts of both books.

The third initiative was in the form of a book, Our Wish-fulling Gem Part 2: A Biography of His Holiness the Dalai Lama” (Library of Tibetan Works & Archives, Dharamsala, 2025), by educationist Chophel compiling the details on visits by His Holiness the Dalai Lama throughout the world outside of India from 2011 till 2018. Additionally, this second volume also has details on His Holiness’ visits within India from 2011 onwards. As in the first volume, in this book, too, the author provides an overview of His Holiness’ meetings and remarks at events big and small in different countries which are “a testament to the enduring influence of one of the world’s most revered spiritual figures.” His first volume, titled “Our Wish-Fulling Gem: A Biography of His Holiness the Dalai Lama” was published in 2022 and covered the first 75 years of His Holiness’ life. The author and I know each other, and I had the opportunity to read a drafts of both books.

In the preface, the author explains His Holiness’ impact saying, “He taught the world how to laugh in the midst of chaos. He revealed that the purpose of our life is to be happy. He has taught the world the art of happiness and left a lasting imprint on the world.”

His Holiness’ message on the importance of compassion permeates through the book. The author talks about the Southern Methodist University in Dallas in Texas bestowing an honorary doctorate from the university for ‘his lifelong leadership in promoting peace, compassion and inter-religious understanding.’ In fact, there are 178 mentions of the term “compassion” in it.

Although His Holiness has relinquished his political role (see more in the next paragraph), his relevance to the world and more so to the Tibetan people continues. This book is not, and does not claim to be, a scholarly appraisal of His Holiness the Dalai Lama’s travels. Rather, it is a wholesome compilation of all his visits from 2011 to 2018 that provides the readers with an understanding of the Dalai Lama’s impact on the several thousands of people throughout the world who attended his talks or who had the opportunity to interact with him.

An interesting impact of the Dalai Lama is an outcome of something from which he intentionally withdrew himself, namely his political authority that he devolved to an elected Tibetan leadership in 2011, as mentioned above. Following his announcement in March that year, I participated in a Congressional Executive Commission on China Roundtable on “The Dalai Lama: What He Means For Tibetans Today” on July 13, 2011 in Washington, DC. In my presentation, I explained one of the implications of this devolvement of political authority saying, “It bursts the myth about the return of the “Old Society”: One of the scare tactics that the Chinese authorities continue to use among Tibetans in Tibet to maintain control is to project the period during independent Tibet (referred to as the “old society” as opposed to life under China, which is the “new society”) as horrendous, and to say that the Dalai Lama’s aim is to restore the “old society.” The Dalai Lama’s decision including the removal of the name of the government of Ganden Phodrang (that ruled Tibet) from the present Administration in exile takes away the opportunity for the Chinese to continue resorting to this myth.”

In any case, in this 90th birthday year of His Holiness the Dalai Lama (being observed by the Central Tibetan Administration as “Year of Compassion”) we will be seeing many more of such events in different parts of the world. Indeed, a period for rejoicing, recommitment and reflection for all of us who are well-wishers or devotees of the Dalai Lama.