A Phoenix TV correspondent had asked a two-part question: “Despite China’s firm opposition, some countries have been inviting him [the Dalai Lama] for a visit, and he has just concluded a visit to Europe. Will China take more steps to express such opposition? On the religious freedom in Tibet, in your opening remarks you said that we must ensure the Chinese orientation of religions. Will that be more work done in this regard?”

In his response, Zhang repeated the Party line about the Dalai Lama being “a leader of a separatist group that is engaging in separatist activities”, and therefore the Chinese Government oppose any meetings by governments and others with him.

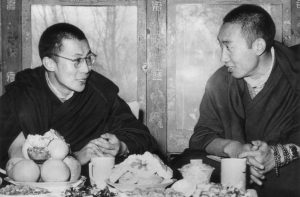

However, it is a fact known not only to the international community, but even to the Chinese themselves that the Dalai Lama has since the mid-1970s been seeking a solution for a future Tibet that is within the framework of the People’s Republic of China. It is precisely for this reason that he could respond immediately and positively to the overture of then Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping in 1979 who said other than the independence of Tibet anything else can be discussed and resolved. United Front leader Ding Guangen repeated, in 1992, this assurance by Deng Xiaoping and by a Chinese official spokesperson in 1993. On August 25, 1993, Xinhua quoted a spokesperson of the Chinese Foreign Ministry as saying, “The affairs of Tibet are an internal business of China’s and the door of negotiations between the central government and the Dalai Lama remains widely open. Except independence of Tibet, all other questions can be negotiated.”

The Dalai Lama had subsequently concretized his initiatives on the future of Tibet through his Middle Way Approach that called for genuine autonomy for the Tibetan people, something actually guaranteed (but not implemented) in the Chinese Constitution and Law on Regional Ethnic Autonomy. The Chinese authorities know that the Dalai Lama was not calling for “separatism”, but not having the political courage to acknowledge this, they sought recourse to semantics by saying they are against “semi-independence or disguised independence”.

Following the devolution of political power by the Dalai Lama to the elected Tibetan leadership in 2011, the Central Tibetan Administration has continued to be committed to the Middle Way Approach. Governments, even those close to China, are aware of this Tibetan position, as are people who know about the Dalai Lama, including the thousands of Chinese who are able to know the truth.

Since the Dalai Lama continues to garner unimaginable (for Chinese leaders) international public support, and since he has begun to focus on the younger generation (who are in schools) that can contribute positively to humanity, Zhang makes it seem as if the universities are the only space that is available now to the Dalai Lama.

During his visit to Latvia in September this year, when asked about some government leaders hesitating to receive him, the Dalai Lama said: “That’s ok,” my visit is entirely non-political. I’m not disappointed. The world belongs to its 7 billion people and each country belongs to its population, so I consider the general public to be more important.”

Which Chinese leader can hope to fill a stadium or an auditorium (often for several days at a stretch and with people willing to buy tickets)? The Dalai Lama does this all the time (most recently during his talks in Pisa and Florence in Italy in September).

While talking about money, unless the interpreter was wrong, Zhang says “Usually a university paid the Dalai to give a speech” making it seem as if His Holiness is making money out of them. Those who organize talks by the Dalai Lama, including universities, and those who attend such talks clearly know that he does not charge money for such events. In fact, the Dalai Lama’s website clearly says, “For your information, as a long-standing policy His Holiness the Dalai Lama does not accept any fees for his talks. Where tickets need to be purchased, organizers are requested by our office to charge the minimum entrance fee in order to cover their costs only.” Since I have had the privilege of being part of his entourage during several visits to North America, I know that at all such public talks by the Dalai Lama where tickets have to be purchased a public accounting of the finances is done at the conclusion. Where there is surplus money they are allocated to local and other charity work. None of the money goes to him.

On the matter of protection of Tibetan Buddhism, Zhang has the audacity to claim that “Tibetan Buddhism originated in ancient China; it is a special form of religion that originated within China.” He goes on to add that although it is true that it has been “influenced by other religions and other cultures” (read India), “but it is not acquired religion. It is originated [sic] within China; it has its roots in China. So it is an example of being Chinese. It has Chinese orientation.”

Zhang might be saying this to lay the ground for legitimizing the Chinese Government’s interference in Tibetan Buddhism; but anyone having only a cursory knowledge of Tibetan Buddhism would know that the spiritual knowledge came from India and had nothing to with China. For God sake, there is a reason why the term “Buddhism” is included in Tibetan Buddhism, because it is the religion founded by Lord Buddha.

Zhang’s utterance that Tibetan Buddhism “has Chinese orientation”, lays bare China’s political agenda of wanting to Sinicize Tibetan Buddhism and make it Chinese.

Thus, Zhang Yijiong’s statements might serve the narrow interest of that section of the Chinese leadership that does not want a resolution of the Tibetan issue and does not want the Tibetan people to enjoy their fundamental human rights, including religious freedom. But does this serve the long-term interest of China? Why should the Chinese people be concerned about views of individuals like Zhang?

Referring to viewpoints like this, Chinese intellectual Wang Lixiong said in 2009 in Washington D.C. while receiving the International Campaign for Tibet’s Light of Truth award, on behalf of the Chinese scholars, “This is the major long-term obstacle to resolving the Tibet question. Removing this obstacle should be the mission of China’s intellectuals, for there is no greater knowledge than the truth”.

Wang also added China’s fake propaganda and information blackouts prevented most Chinese from understanding that the Dalai Lama was seeking a non-violent “Middle Way” of greater rights for Tibetans under Chinese rule.

In fact, a 12-point suggestion, signed by several hundred mainland Chinese scholars, in the wake of the widespread demonstrations in Tibet in 2008 included a call to the Chinese Government not to do things that are not in the interest of China itself.

Its Point 4 reads: “In our opinion, such Cultural-Revolution-like language as “the Dalai Lama is a jackal in Buddhist monk’s robes and an evil spirit with a human face and the heart of a beast ” used by the Chinese Communist Party leadership in the Tibet Autonomous Region is of no help in easing the situation, nor is it beneficial to the Chinese government’s image. As the Chinese government is committed to integrating into the international community, we maintain that it should display a style of governing that conforms to the standards of modern civilization.”

As the new Chinese Party leadership begins their work, they should also be mindful of Point 12 of the suggestions: “We hold that we must eliminate animosity and bring about national reconciliation, not continue to increase divisions between nationalities. A country that wishes to avoid the partition of its territory must first avoid divisions among its nationalities. Therefore, we appeal to the leaders of our country to hold direct dialogue with the Dalai Lama. We hope that the Chinese and Tibetan people will do away with the misunderstandings between them, develop their interactions with each other, and achieve unity. Government departments as much as popular organizations and religious figures should make great efforts toward this goal.”

If the Chinese leadership in fact believes that the People’s Republic of China is a multi-ethnic nation, with Tibetans being equal citizens, they should walk the talk. Zhang Yijiong’s statement does not do that.

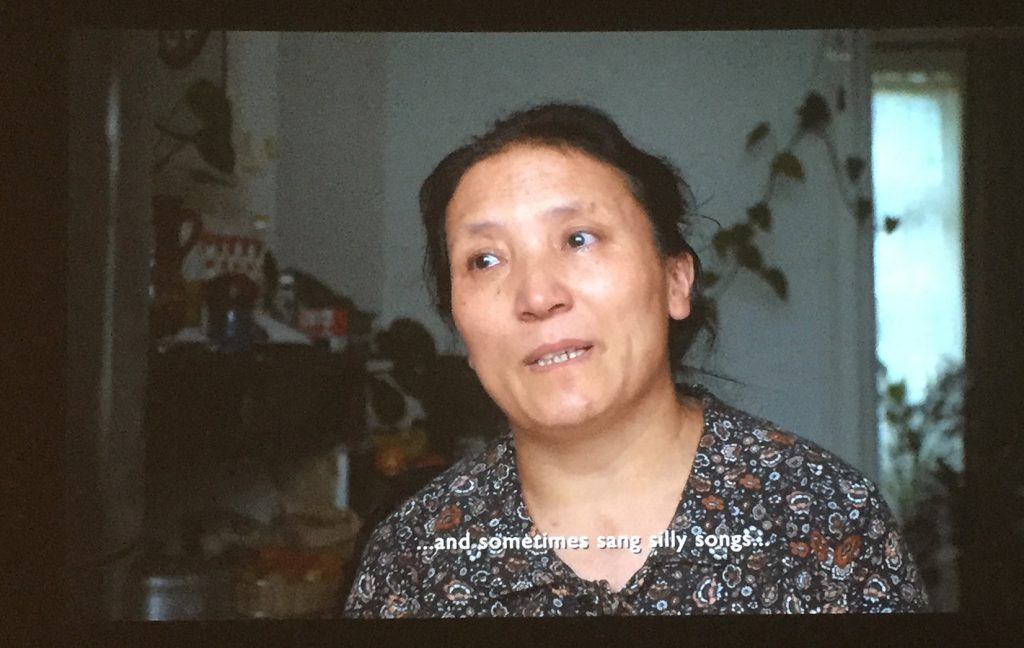

In ‘Two Friends’, a single channel video depicts 22-year old former monk, Ngawang Norphel, blackened almost beyond recognition as a human being, speaking on camera to monks who are tending him after his self-immolation.

In ‘Two Friends’, a single channel video depicts 22-year old former monk, Ngawang Norphel, blackened almost beyond recognition as a human being, speaking on camera to monks who are tending him after his self-immolation.

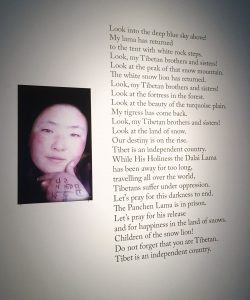

On the wall, lines from a poem left by 17-year old nun Sangye Dolma, whose luminous and beautiful face appears here more as a classical painting than selfie, reveal a message of hope beyond despair. Like many of those who set themselves on fire in Tibet, it is not addressed to the U.N., the international community but to fellow Tibetans, written in solidarity, and urging them to “Look my Tibetan brothers and sisters! Look at the land of the snow. Our destiny is on the rise. […] Children of the snow lion! Do not forget that you are Tibetan. Tibet is an independent country.”

On the wall, lines from a poem left by 17-year old nun Sangye Dolma, whose luminous and beautiful face appears here more as a classical painting than selfie, reveal a message of hope beyond despair. Like many of those who set themselves on fire in Tibet, it is not addressed to the U.N., the international community but to fellow Tibetans, written in solidarity, and urging them to “Look my Tibetan brothers and sisters! Look at the land of the snow. Our destiny is on the rise. […] Children of the snow lion! Do not forget that you are Tibetan. Tibet is an independent country.”