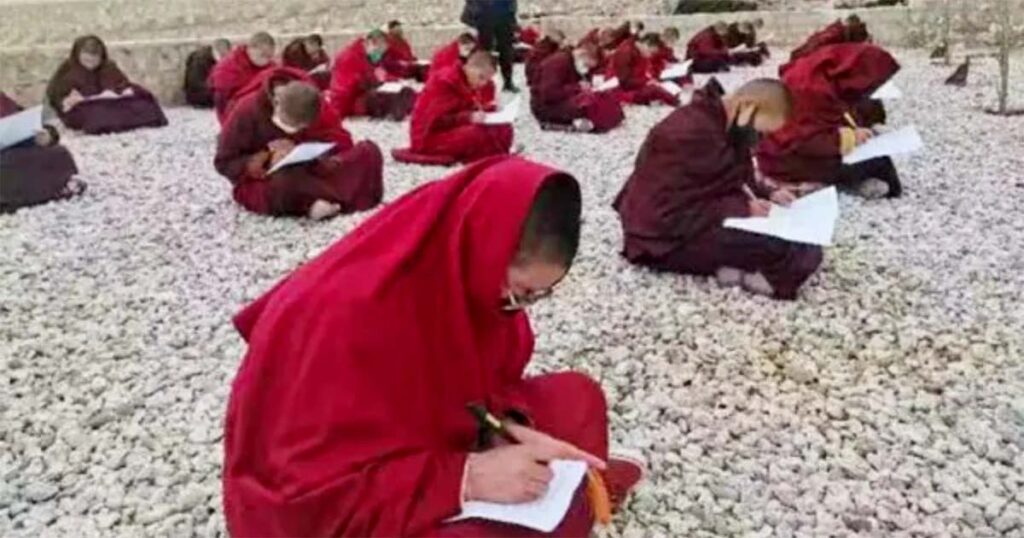

A “knowledge contest” for Tibetan monks and nuns, in which they were asked to demonstrate their knowledge of the party’s ideology. The compulsory event was organized last summer by the United Front Department of the Communist Party of China. (Source: WeChat/xztzb.com)

A look at Tibet reveals that a new cultural revolution is taking place there. Beijing’s campaign affects all areas of Tibetan life and penetrates deep into even the most private areas of people. The “Four Old Evils” that the Red Guards fought against at the time are now defined much more comprehensively, however, and those in power are no longer just targeting the traditional social elites. What the Chinese Communist Party’s new cultural revolution in Tibet wants to destroy is nothing less than the independent cultural, religious and national identity of the Tibetans. This is to be completely eradicated, and Tibetans are to be turned into Chinese.

The new cultural revolution in Tibet is taking place on many levels simultaneously. It uses political, cultural and economic measures in conjunction with comprehensive surveillance and control of all areas of life. The Chinese rulers are relying on systematic and long-term “Sinicization,” a term that refers to the forced assimilation of Tibetans. This goal is served, for example, by the forced placement of a large number of Tibetan children and young people in state boarding schools. In these schools, systematic efforts are made to alienate the young people from their mother tongue and their cultural and religious traditions.

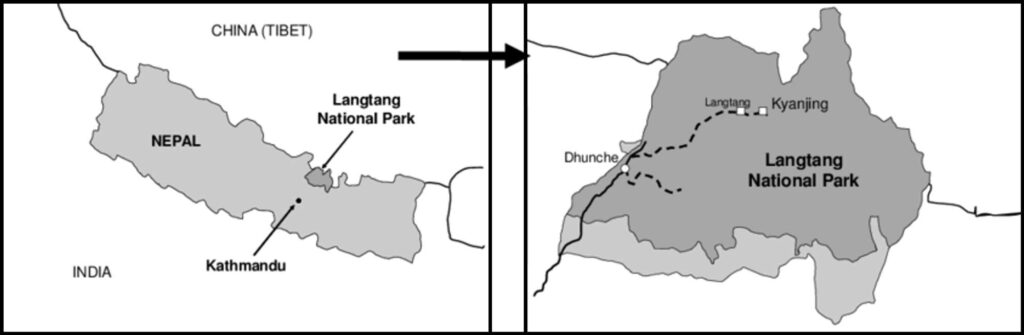

By forcibly settling Tibetan nomads, the Chinese rulers are trying to eradicate a way of life that gives Tibetans their identity and, at the same time, are deliberately creating a situation of economic dependence. The forced integration of Tibetans into state work programs is also intended to serve this purpose.

New Cultural Revolution wants to adapt Buddhism “to socialist society”

Another focus of Beijing’s new cultural revolution in Tibet concerns Tibetan Buddhism. The Chinese rulers want Buddhism to be completely at the service of the Communist Party’s rule and to “adapt to socialist society.”

In addition, Communist Party officials stress at every opportunity the obligation of Tibetan Buddhist monks and nuns to study General Secretary Xi Jinping’s statements on religious work. “Patriotic education” is once again widespread in Tibet’s monasteries, and monks are even forced to publicly defame the Dalai Lama. In some areas, even the prayer flags that are so inseparably associated with Tibet are banned.

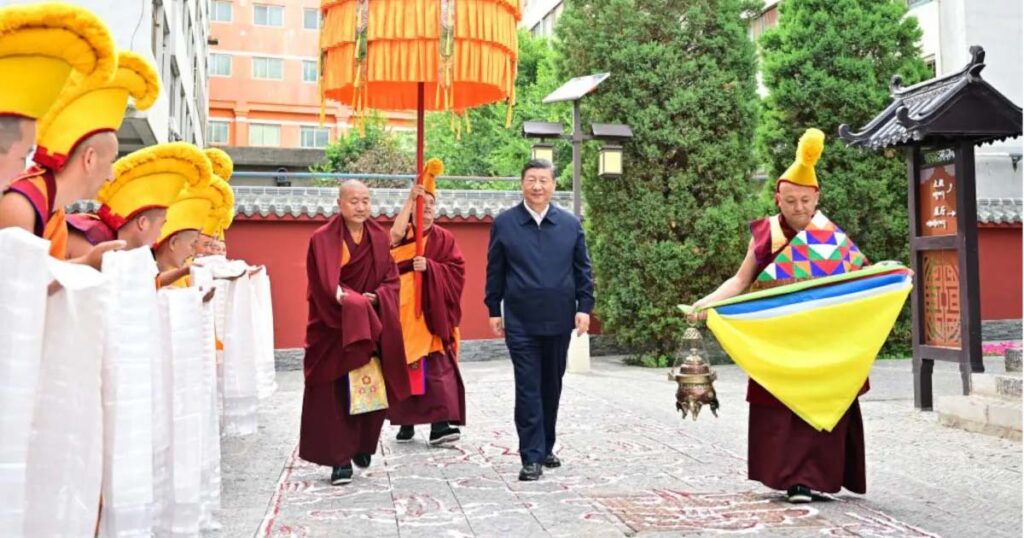

A Communist Party leader is venerated like a Buddhist dignitary: Xi Jinping visits Tsongkha Gon monastery. (Source: xztzb.gov.cn)

The new cultural revolution in Tibet is clearly a top priority. This became clear recently when several top officials visited Tibet almost simultaneously, including Xi Jinping and Wang Huning, the number 1 and number 4 of the Communist Party’s inner circle of leadership, and Shi Taifeng, the head of the United Work Front. The message spread by Beijing’s propaganda media was always that the “Sinicization” of Tibet must be consistently pushed forward.

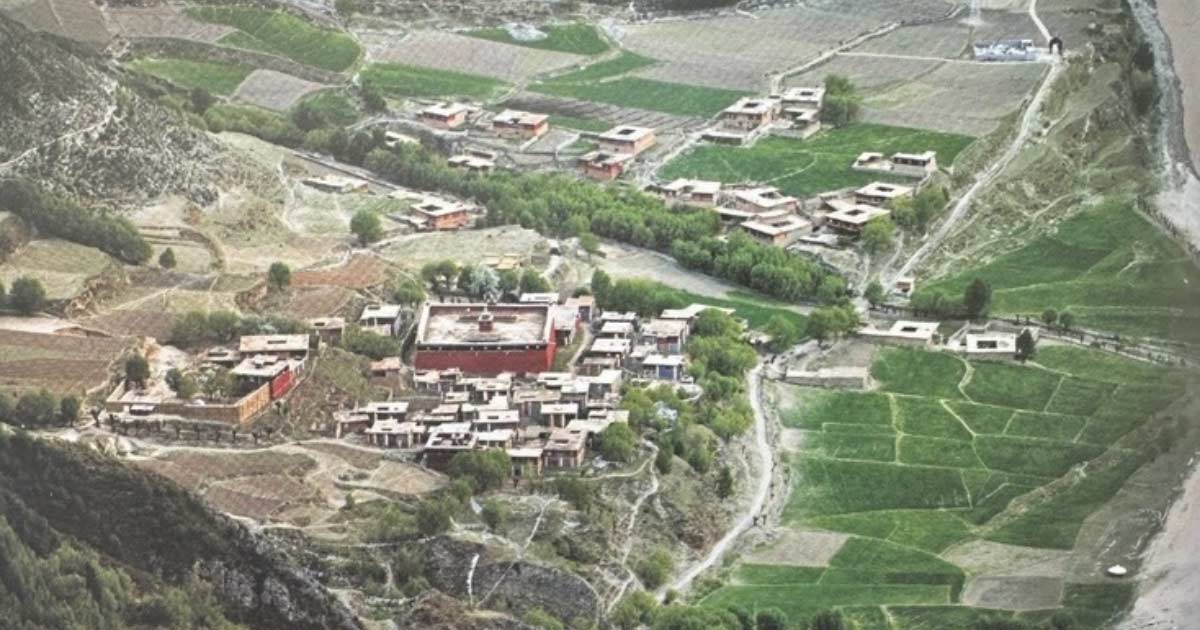

Destruction of Buddhist centers, demolition of Buddha statues

As in the days of the first Cultural Revolution, Beijing is still using brute force against Buddhist institutions in Tibet today, for example when the accommodations of thousands of monks and nuns in the Larung Gar and Yachen Gar Buddhist study centers are demolished. Or when, as happened in December 2021, the local Chinese rulers have a 30-meter-high Buddha statue and 45 large Buddhist prayer wheels destroyed. At the core, however, the CCP leadership is trying to destroy Buddhism from within; the outer shell should appear intact on the surface, while the actual substance has long since disappeared.

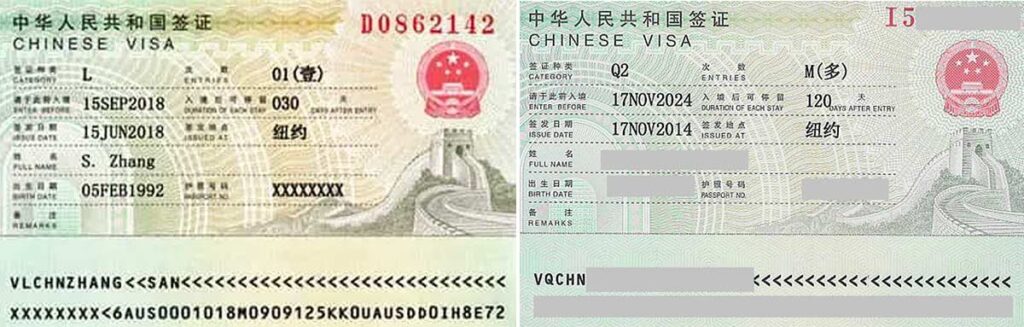

The communist rulers, who are committed to atheism according to their statutes, claim to decide on the successor to the Dalai Lama and all other reincarnations of Tibetan Buddhism. Beijing has also made the Buddhist Association of China (BAC) another building block in its strategy for the forced assimilation and transformation of Tibetan Buddhism. This supposedly non-political organization is intended to help appoint Tibetan Buddhist dignitaries in the interests of the Communist Party.

A cultural revolution took place in Tibet before 1966

The Cultural Revolution that took place in Tibet between 1966 and 1976 differed considerably from the Cultural Revolution in China from the outset. Although the campaign in Tibet, which was primarily carried out by the Red Guards, was also directed against the so-called “Four Old Evils”, which meant “old ways of thinking”, “old cultures”, “old habits” and “old customs”, to Tibetans they must have seemed like an intensified version of the brutal oppression that the Chinese communists had begun since the beginning of the violent conquest and occupation of the country more than a decade earlier. In fact, a Cultural Revolution had already taken place in Tibet before 1966.

After the brutal suppression of the Tibetan popular uprisings in the 1950s by communist forces, the Chinese rulers in Tibet established an absolute tyranny. Not only did countless people fall victim to this, it was also accompanied by the systematic destruction of monasteries, temples and cultural monuments. The majority of the population was forced into newly established people’s communes, where they were to be re-formed into class-conscious proletarians, while the members of the former upper class were to “reform” themselves through forced labor (“reform through work”).

Tsadi Tseten Dorje, the former mayor of Lhasa, is denounced during a “Thamzing” struggle session in Lhasa. The placard around his neck lists Dorje’s alleged crimes: “Counter-revolutionary, deceitful ringleader and promoter of unrest, butcher, murderer and slaughterer of the working masses.” (Photo: Tsering Dorje)

The struggle and criticism sessions known in Tibet as “Thamzing” had a particularly traumatic effect. In these sessions, selected victims were publicly humiliated and tortured until they confessed their alleged “guilt.” In 1976, the Tibetan government in exile published a collection of testimonies from Tibetan refugees from 1958 to 1975 under the title “Tibet Under Chinese Communist Rule.” This collection provides a good overview of the Chinese reign of terror in Tibet during this period. In accordance with their Marxist ideology, the Beijing rulers assumed that these measures would automatically dissolve the national, cultural and religious identity of the Tibetans within the framework of the People’s Republic of China. In fact, things turned out differently. Despite everything, the Tibetans have retained their identity and to this day the vast majority do not want to be made into Chinese.

Beijing’s new cultural revolution also promotes personality cult

The personality cult that characterized the Cultural Revolution has also been resurrected, but at its center is no longer the “Great Helmsman” Mao Zedong, but the “navigator” Xi Jinping. And the “little red book” with Mao sayings that one should be able to recite by heart has been replaced by the “little red app”. Communist party cells have since organized competitions, wrote Kai Strittmatter in the “Süddeutsche Zeitung”: “People collect points in the apps: reading Xi speeches, watching Xi speeches gives points, answering Xi quiz questions even more. Usage time and score are forwarded directly to the examiners.”

In this respect, it is hardly surprising that the new magic word of Beijing’s new cultural revolution is “Xi Jinping’s cultural ideology”. Explanations of the concept, which is also translated as “Xi Jinping’s cultural thought,” can be found on numerous websites of the Chinese Communist Party and the state agencies dominated by the Communist Party. The Chinese rulers in Tibet are openly targeting the cultural sector with this. The Chinese propaganda media recently reported on a large-scale seminar on “Xi Jinping’s cultural ideology” in the eastern Tibetan prefecture of Kardze. It is to be expected that this latest component of China’s new cultural revolution in Tibet will be expanded to all parts of the country in the future. It remains to be hoped that the Tibetans will maintain their resilience in the face of the new cultural revolution.

* The photo at the top shows a “knowledge contest” for Tibetan monks and nuns, in which they were asked to demonstrate their knowledge of the party’s ideology. The compulsory event was organized last summer by the United Front Department of the Communist Party of China. (Source: WeChat/xztzb.com)